Let us begin with a ghost story. In 1872, fourteen-year-old Agnes McDonough announced that she was communicating with the spirit of her deceased father. She was part of a community of Irish Americans who settled in Virginia City, Nevada, home to the fabulous Comstock Lode and the Big Bonanza (giving its name to a famous television show). Crediting her father’s ghost, the young girl revealed insights about the afterworld, all scrutinized by a local priest who hoped to control the sensational aspects of the incident.

At roughly the same time, Peter O’Riley, another Irish emigrant, claimed that spirits told him where to begin digging for the next great mineral strike. He had participated in the 1859 discovery of the Comstock’s gold and silver. Sadly, O’Riley had sold his interests for a few thousand dollars, missing out on the hundreds of millions the deposit would yield. Enticed by voices he claimed to hear, the ageing miner hoped to find a way to redeem himself by locating – and keeping – the next bonanza. O’Riley never found his second pot of gold, and he ended his days in an asylum.

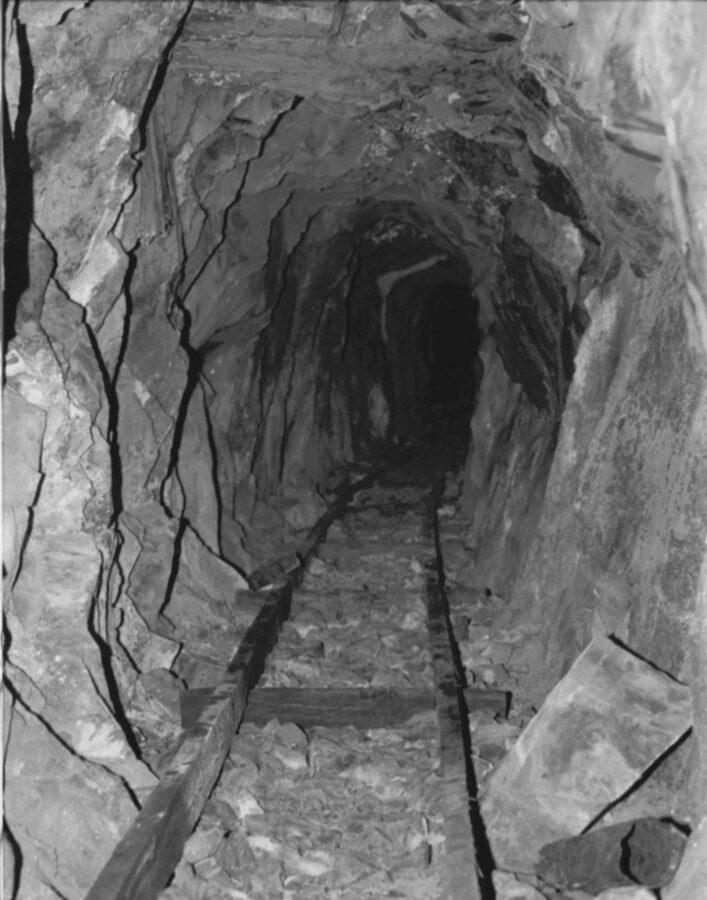

Agnes McDonough and Peter O’Riley welcomed their messengers from beyond for different reasons. At the same time others believed in spirits deep in the mines, but workers tended to dread them. In the American West, underground ghosts were often blurred with tommyknockers. These descendants of Cornwall’s knockers were a variety of pixy that worked underground. Although sometimes tommyknockers warned of danger, miners generally feared them, together with ghosts of the dead.

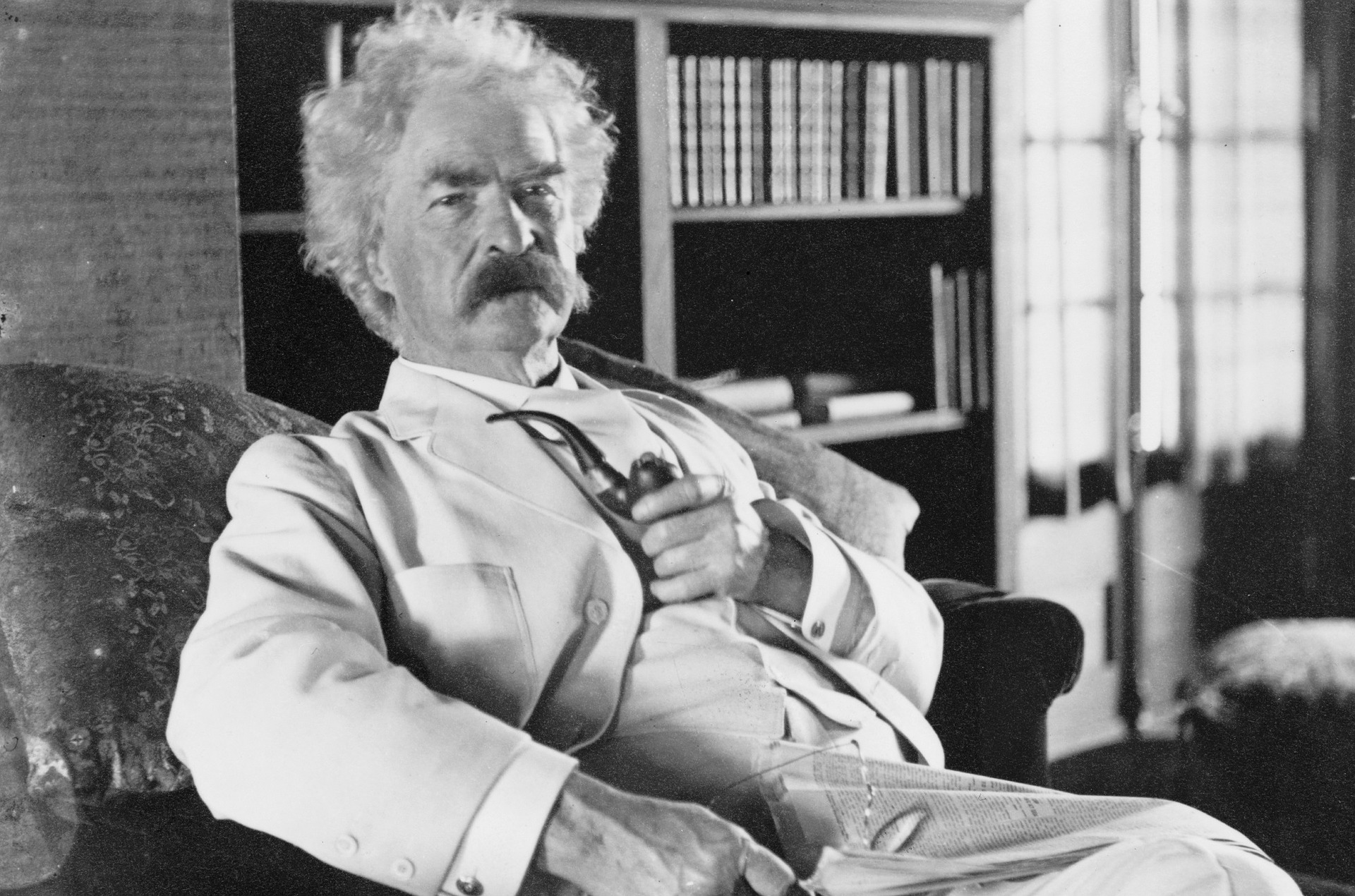

Despite the abundance of Irish emigrants, the West was much more complex than that. As Mark Twain observed of Nevada, ‘all the peoples of the earth had representative adventurers in the Silverland.’ Many of these people believed in ghosts, but perspectives differed, in part depending on place of origin. Because of this complexity, generalizing can be difficult.

In 1980 I resolved to reach beyond the ghosts, and to tackle the folklore of the Wild West in general.

Early on, it seemed that mining traditions were key to unlocking this puzzle. In 1942, the respected folklorist Wayland Hand (1907-1986) published a pair of articles on ‘Californian Miners’ Folklore,’ the first about aboveground traditions and the second peering below. It was natural to turn to Hand’s work, still fresh in the academic literature. Now, eighty years after his seminal publications, Hand remains a giant in the field. Yet despite his legacy, something did not seem right.

This is where the extraordinary website, #FolkloreThursday, stepped in. After decades of nibbling around the edges of mining folklore, I was yet to put my arms around a larger part of Wild West traditions. #FolkloreThursday offered an unexpected solution.

#FolkloreThursday is a generous forum where people with diverse perspectives and interests share thoughts and research. For me, the website offered two valuable services that helped me ‘crack the nut’ of the subject. Firstly, it provided a constant parade of easily digestible articles, filled with inspiration to widen one’s perspective. Secondly, #FolkloreThursday allowed me to test new ideas, which amounted to just enough additional nibbling at edges to deal with broader horizons.

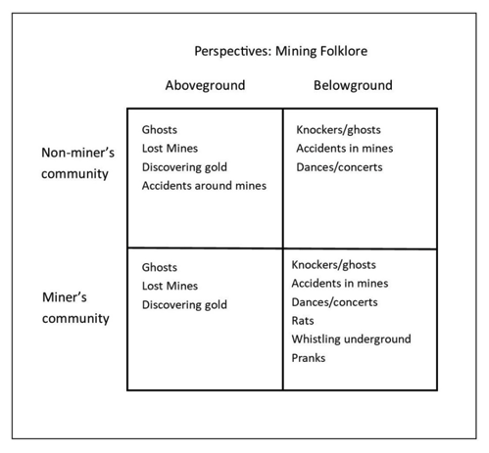

A key moment in this process was realizing how Hand had led me astray. This is not to disparage an excellent scholar: I doubt I would have been able to start, let alone finish, my task without his significant contributions. That said, Hand’s division of mining folklore into above and below ground did not address the larger problem.

Thanks to the encouragement of Dee Dee Chainey and Willow Winsham and their team at #FolkloreThursday, I arrived at a way to understand the region’s mining folklore, placing it in four quadrants, rather than Hand’s bifurcation:

This is not a remarkable insight. Anyone could have come to this, but by continuing to fall back on Hand’s dichotomy, I was stuck. #FolkloreThursday unlocked the door.

The revelation was liberating. With constant change, the early folklore of the American West is difficult to embrace. People came from everywhere, and many then left. Traditions mixed even as new ones took shape. A rich, multilayered tapestry emerged, always in flux. In addition, occupational folklore was the domain of the insiders, and yet, outsiders also had points of view, each differing depending on place of origin.

Again, this is not an extraordinary observation, but it led to the solution I sought. In 2021, I completed a book-length manuscript of Wild West folklore that includes but also reaches beyond mining. The gate had opened to allow me to realize the ambition, now over forty years old, to address the folklore in the historical West.

So, then, what can be made of the ghosts who spoke to Agnes McDonough and Peter O’Riley? Nineteenth-century Americans were leaning toward a new approach to spectres, but change was uneven. Several decades before, a priest would likely warn McDonough of the dire, even deadly, consequences of conversing with the dead.

Similarly, earlier in the century, O’Riley’s insanity might have been attributed to contact with spirits; instead, many of his peers regarded his professed otherworldly guidance as a symptom of his mental instability. The ghost of the second half of the nineteenth century had lost its shroud and chains, features depicted in A Christmas Carol (1843) by Charles Dickens. It had become less threatening.

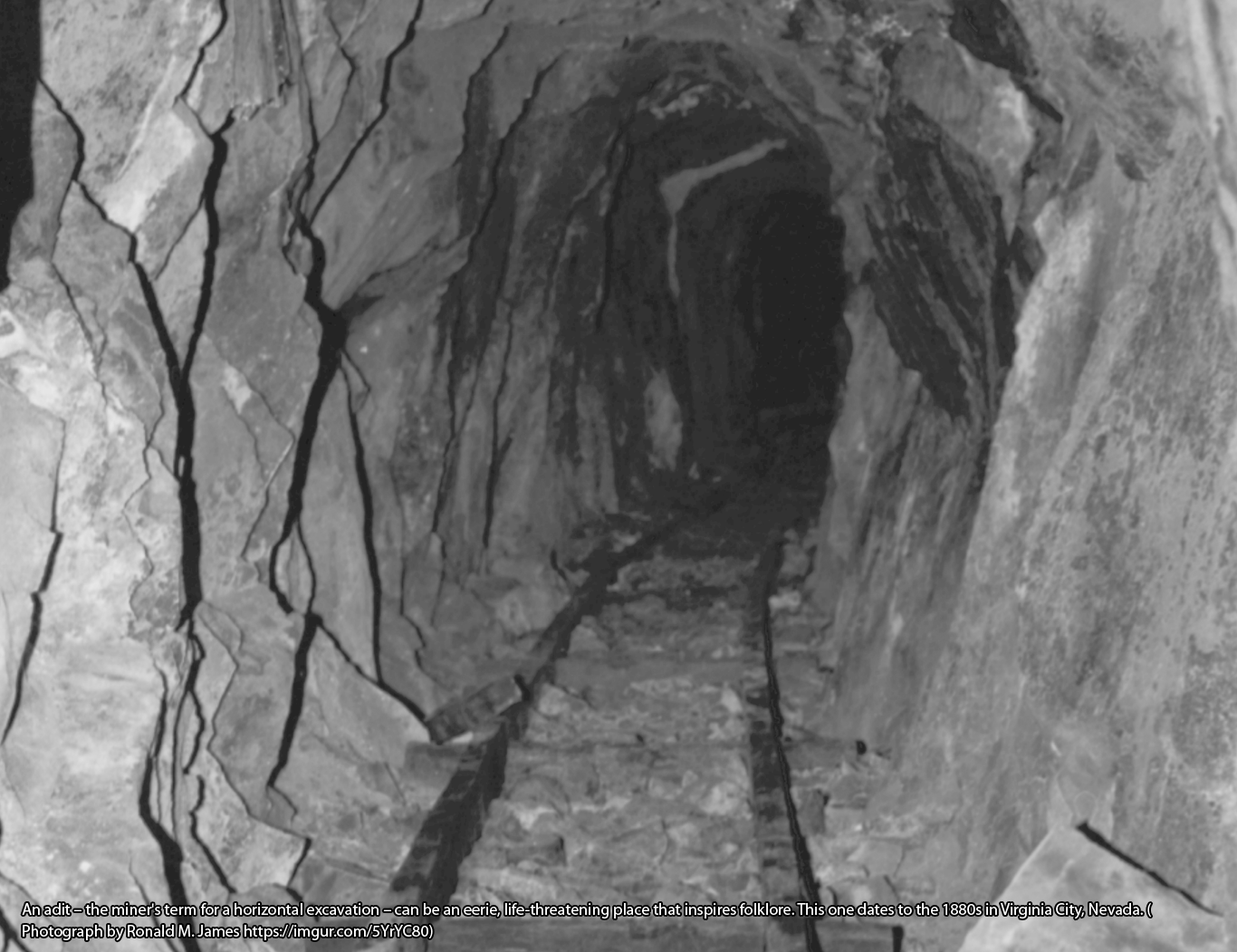

Underground, older attitudes persisted. Danger remained, and terror lingered. Ghosts compounded the spine-tingling panic that threatened to overcome a miner when a creak reverberated in the depths, sounding in a way that seemed menacing. Perception was no doubt different from miner to miner and place to place, making a summary of a shared perspective as elusive as the knockers and ghosts themselves.

Key here is that miners perceived underground ghosts unlike the way they were viewed on the surface. At the same time, those aboveground understood that mining traditions about tommyknockers and ghosts existed, but their perspectives were apart from those of the workers.

In the final decades of the nineteenth century, many no doubt still felt the horror and dread once commonplace when dealing with the souls of the departed. Nevertheless, spirits were shifting to a new stance. Today, ghost hunters in Virginia City seek remnants of the dead, hoping to capture them on film or to record their mutterings. Once feared entities, ghosts have been domesticated. They are like once-dangerous predators, now incarcerated in zoos, exhibited. People gaze at them in safety, reinforcing humanity’s false view of itself, in total mastery of the world. Despite what horror films may depict, the danger ghosts formerly represented is all but gone.

It is a difficult to fathom this complex mix of diverse viewpoints and changing traditions over the decades. Many have helped in this process, but at this moment, it is appropriate to extend my gratitude to #FolkloreThursday.