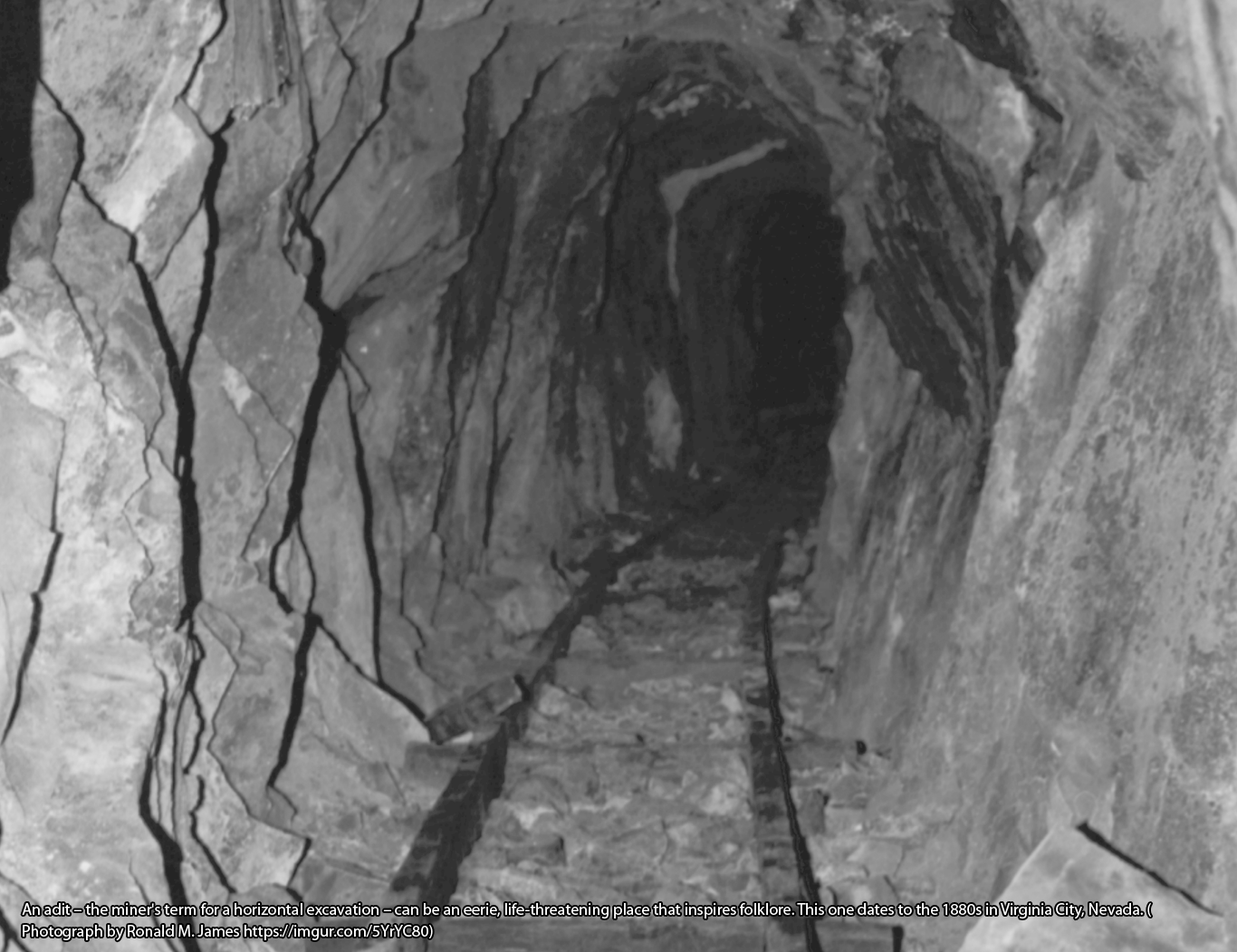

Gold! The very word fuels the imagination. And when that furnace is stoked, folklore is not far behind.

Legends of lost mines are at the heart of traditions inspired by gold, greed and dreams of sudden wealth. Tales of mines won and lost are international, but they are especially common in the West of the North American continent. The most of famous of these is the Lost Dutchman Gold Mine, usually associated with the Superstitious Mountains east of Phoenix, Arizona in the American Southwest.

The Dutchman in question is Jacob Waltz (ca. 1810-1891), a German – or ‘Deutsch’ – immigrant who became the focus of stories about an enormous deposit of gold that was found and then lost. Some accounts feature a second German: this is evidence that the legend has circulated for decades and evolved into distinct variants.

The fact that there are many other Western ‘lost mines’ underscores how integral these legends are to American folklore. These narratives often feature an old prospector who wanders out of the wilderness with gold in his pockets. He either cannot remember where he found the treasure, or he is delirious with sunstroke. Either way, he dies after revealing only a few clues about where he had been. This inspires subsequent explorers who attempt to retrace the old man’s steps, to find the vein of gold that had been found, but then was lost. Many of these subsequent efforts become woven into a larger legend complex.

Alternatively, a young ‘tenderfoot’ takes the place of the old coot. In this case, an inexperienced newcomer emerges from the wilderness with gold in his pockets. A snowstorm occasionally covers his trail. He was not aware that he found anything significant until others tell him the value of his specimens, but then it is too late: he cannot retrace his inexperienced steps back to the bullion he had found.

There are many other variants, but they all share the motif of a spectacularly rich gold deposit having been discovered, only to have the claimant unable to retrace his steps or dying before disclosing the exact location. This initial discovery is frequently followed by accounts of other people attempting to find the lost gold mine. More deaths sometimes ensue.

Folklorist Caroline Bancroft pointed out in 1943 that legends of lost mines are closely related to two other types of narrative. This includes stories about ‘lucky strikes’, the peculiar circumstances of how rich ore was discovered. Often legends of lost mines include this as an introduction, but not all lucky strike mines are lost. Many examples of the Lucky Strike story stand alone as a narrative that describes – or embellishes on – how a prosperous mining district was founded. The initial discovery is commonly tied to an animal – a dog running off, leading its owner on an untrodden path or a donkey kicking a rock reveals the gleam of gold. Many other motifs figure into this complex of stories.

Bancroft also suggested that legends about buried pirate treasure and other forms of hidden wealth are reminiscent of the lost mines. We can recognize this motif in accounts of Nazi gold shipments, the hidden loot of robbers or sunken Spanish galleons full of bullion. There is a difference, however. In these cases, the people who hid the wealth are often later killed, leaving rumours of treasure that was abandoned. Any form of riches can inspire legends, but folklore consistently gravitates to gold, which is often the common denominator.

Bancroft proposed that only regions with ‘remoteness and great distances’ easily foster and perpetuate lost mine legends. She found that in her own state of Colorado stories about discoveries of ore that could not be relocated inspired thorough prospecting in places where geography was limited, and so prosperous ore was rediscovered or proven to be fictional. Either way, the legends died out. Elsewhere in the American West – and in the world – where expanses defy easy reconnaissance, legends of lost mines can persist.

Historically, one of the oldest lingering rumours of elusive gold centred on Ophir, the fabled mines of King Solomon. Much of the modern perception of this lost treasure draws from an 1885 novel by Sir H. Rider Haggard, featuring the hero-adventurer Allan Quatermain. Nevertheless, the fascination with the biblical king’s epic wealth is centuries old. Because of the allure of these riches, many subsequent mines took the name ‘Ophir’ to suggest that they boasted gold on a ‘biblical’ scale.

Similarly, belief in Eldorado, the fabled New World city of gold, inspired Spanish explorers for many decades. It also lured Sir Walter Raleigh, the famed English adventurer, to a final fateful expedition: in 1617, he sought Eldorado in Guiana. He sent his son to find the treasure, resulting in the young man’s death. Raleigh returned to England, and King James I had him behead for the consequences of his pursuit of gold.

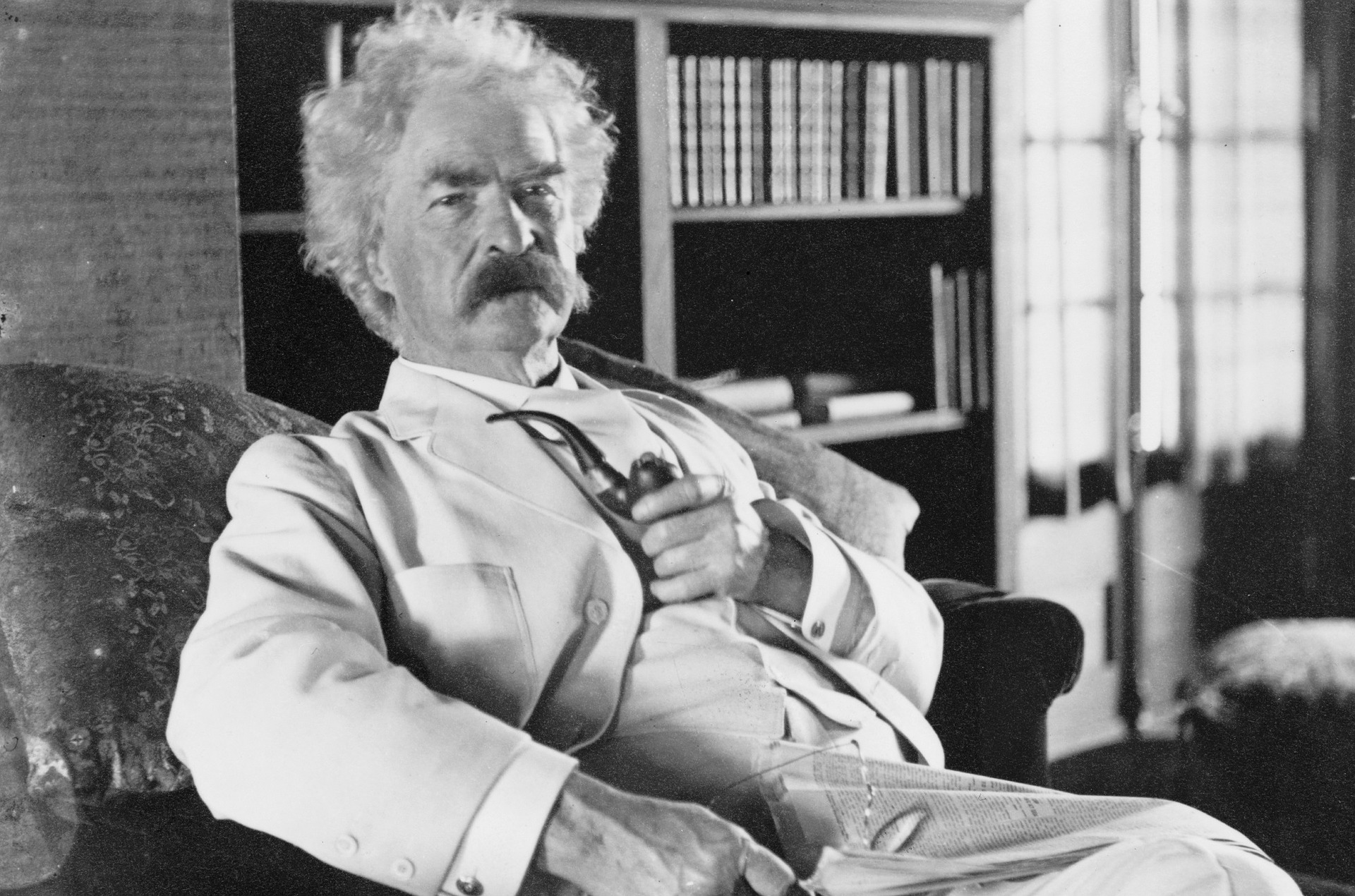

In the poem, ‘Eldorado’, Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849) addresses the romantic but often futile quest for legendary wealth. Poe wrote the poem as news of California’s vast reserves of gold captured international attention, attracting tens of thousands with the same emotional chord of easy gold and sudden wealth. The poem ends with an otherworldly assertion that finding lost treasure requires bold persistence, and yet Poe’s warning also hints that Eldorado might not be found in this world, but rather in the ‘Valley of the Shadow’, using a biblical reference to the land of death. ‘Eldorado’ proved to be one of the poet’s final works, a fitting close to his own, transitory-but-brilliant quest for poetic gold:

Gaily bedight,

A gallant knight,

In sunshine and in shadow,

Had journeyed long,

Singing a song,

In search of Eldorado.

But he grew old—

This knight so bold—

And o’er his heart a shadow—

Fell as he found

No spot of ground

That looked like Eldorado.

And, as his strength

Failed him at length,

He met a pilgrim shadow—

‘Shadow,’ said he,

‘Where can it be—

This land of Eldorado?’

‘Over the Mountains

Of the Moon,

Down the Valley of the Shadow,

Ride, boldly ride,’

The shade replied, —

‘If you seek for Eldorado!’

At the heart of legends of lost mines and the related accounts of hidden treasure is the realization that many people yearn to ‘win the lottery’, to stumble into wealth. As the eminent mining historian, Duane A. Smith (b. 1937), once proclaimed at a mining history conference many years ago, ‘The American dream is NOT to work hard and get rich; the American dream is to NOT work hard and get rich.’ Nothing speaks to that embedded aspiration more than the idea of finding a lost mine, the location of a treasure or a fabulously rich ore body that was found, lost, and now awaits a new discoverer to claim the wealth. Who has not dreamed if only for a moment, of discovering the secret that will lead to riches beyond imagination?

Recommended Reading from #FolkloreThursday

References & Further Reading

Bancroft, Caroline, ‘Lost-Mine Legends of Colorado’, California Folklore Quarterly, 2:4 (October 1943) 253-63.

———-, Colorado’s Lost Gold Mines and Buried Treasure (Boulder, Colorado: Johnson Books, 2002 [1961]).

Clover, Thomas E., The Lost Dutchman Mine of Jacob Waltz (Phoenix, Arizona: Cowboy-Miner Productions, 1998).

Mitchell, John D., Lost Mines of the Great Southwest (Glorieta, New Mexico: The Rio Grande Press, 1990).

Silverman, Kenneth, Edgar A. Poe: Mournful and Never-ending Remembrance (New York: Harper Perennial, 1991).