The rich body of Cornish folklore, claimed by both the English and the Celtic world, receives a new treatment that evaluates its place in Britain. The Folklore of Cornwall: The Oral Tradition of a Celtic Nation addresses everything from piskies – south west Britain’s fairies – to mermaids, harvest festivals, a corpse visiting his betrothed, and the giants long noted for making the Cornish peninsula their home. And amid all this are the spirits of the mines – knockers together with the tommyknockers, their New World descendants.

In 2007, a miner told me how he was sleeping in an abandoned level of the Golconda Mine in the American West, only to be startled awake by the rapping of tommyknockers. The incident occurred in the 1950s, a half century earlier. With just a hint of a wink, he said he believed that Cornish tommyknockers, the elfin spirits described by his father, were haunting that old mine drift. As it turned out, the most astounding part of the story was that his father had emigrated from the Portuguese Azores, far removed from Cornwall.

For me, it all started with tommyknockers. Four decades ago they led me from the United States to Cornwall and back. In 1976, I began five years of folklore studies under my mentor, Sven S. Liljeblad (1899-2000), and when these transplanted Cornish knockers first came to my notice, I told him about them. He was intrigued, and he encouraged me to pursue them: their ability to thrive in the New World, defusing into the general population, was something that few of their ilk had accomplished after traveling thousands of miles.

Liljeblad, the student of folklore theoretician, Carl Wilhelm von Sydow (1878-1952), burst onto the scene in 1927 with his dissertation about folktales featuring the Grateful Dead: Liljeblad put forward an approach, the “Oicotype method,” which he and von Sydow developed to describe how traditions adapt to environments as they diffuse. In 1939 after opposing the Nazis, Liljeblad fled to the American West to study Northern Paiute and Shoshone language and folklore. Thanks to his remarkable, twisting path, I encountered this luminary from an earlier time.

By 1981, I was studying in Dublin’s folklore archive, which Liljeblad helped organize a half century before. Within that great institution were thousands of books, willed from von Sydow’s collection to the Irish. Among those aging tomes were tastes of Cornwall, an opportunity to pursue a subject I first encountered in the old mines of the West. With a side trip to Cornwall, I was able to follow the trail that led to the publication of The Folklore of Cornwall. Of course, the knockers made certain that many of their compatriots would receive equal treatment, and my focus broadened.

The Folklore of Cornwall attempts to place narratives and beliefs in context. Both England and the Celtic nations claim the distant British peninsula, and its traditions uncomfortably serve these two masters. That said, many folklorists have scorned Cornwall: its collectors described the indigenous droll tellers, professional storytellers, as wilfully altering narratives they had heard, changing them with glee to the hilarity of their audience. This, then, seemed poor terrain to find fossilized remnants of distant times, the inspiration of so many early scholars who hoped to piece together ancient stories and traditions.

Cornwall presents, then, a quandary: its collections were as rich and varied as anything found elsewhere in Britain and yet the art of the droll tellers emphasized creativity rather than preservation. Cornish folklore seemed mutated and standing half way between “modern” England and a romantically-conceived older Celtic world. After years of consideration, I realised that rather than seeing Cornish tradition as spoiled, it was better to understand that its narratives documented accelerated adjustment to a unique environment.

The flexibility of the droll tellers allowed stories to change quickly to suit the situation. For example, boats often took the place of horses found in legends elsewhere but discarded in Cornwall, a land where the sea was ubiquitous. This is the sort of local adaptation that von Sydow and Liljeblad maintained occurred as international narratives diffused from place to place. At the same time, older themes lingered: the Cornish piskies were as bedevilling as their Northern European counterparts. And giants, behemoths much like those from other places, thrived in Cornwall and continue to play a role in local festivals.

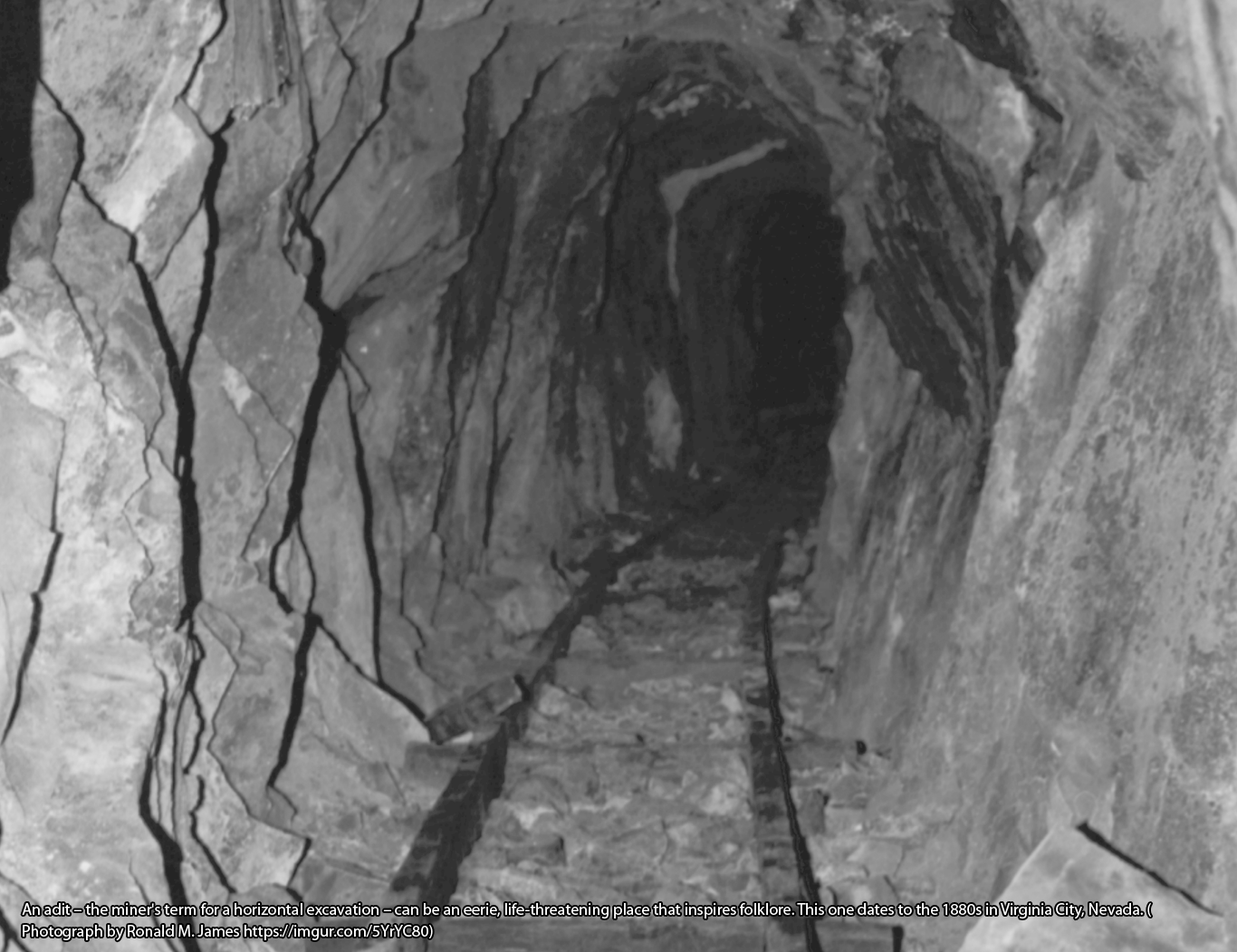

With the omnipresence sea, mermaids were central to Cornish folklore, and with the importance of tin mining to Cornwall, piskies delved into the eerie depths to work as the famed “knockers.” These underground spirits made their presence known by their chilling, knocking sounds, echoing from old drifts. Peering more closely at the Cornish knockers, it is possible to see the shadows of history as it unfolded. Stories of knockers leading miners to wealth were relics of an older time: with nineteenth-century industrialization, miners worked for wages and had little concern about finding a rich “lode” as the Cornish called pockets of valuable ore. In the same way, punishing greed made less sense in the new economy.

Instead, salaried miners relied more on the knockers to warn of danger. Their rapping could serve as a signal of imminent collapse, and with this we can see a pragmatic aspect of a surviving tradition: because miners believed the sounds deep “below grass,” as the Cornish would say, were messages from their elfin co-workers, they paid careful attention to signs that wooden supports might be failing.

The practicality of worker’s folklore combined with the international prestige of Cornish miners to allow for the spread of knockers to the New World, where they were known as “tommyknockers.” It also opened the door for the tradition to be embraced by non-Cornish miners. While the fairies of many Northern European emigrants faded with the first generation, the tommyknockers thrived and continue to linger in the American West as a hallmark of regional tradition. Wayland Hand, the great American folklorists, even documented a New World innovation: miners crafted clay tommyknockers with matchstick eyes and placed them underground to receive bits of food, offerings given with the hope of currying favour.

The Folklore of Cornwall seeks to find meaning in a large body of narratives and beliefs. It attempts to determine whether this remarkable tradition should be regarded as English or as something distinct. Using a method that von Sydow and Liljeblad devised nearly a century ago, The Folklore of Cornwall suggests that the Cornish stand apart. We can hope this discussion will continue as this volume frames the traditions of the remote peninsula within a larger context, to give meaning to what the droll tellers told.

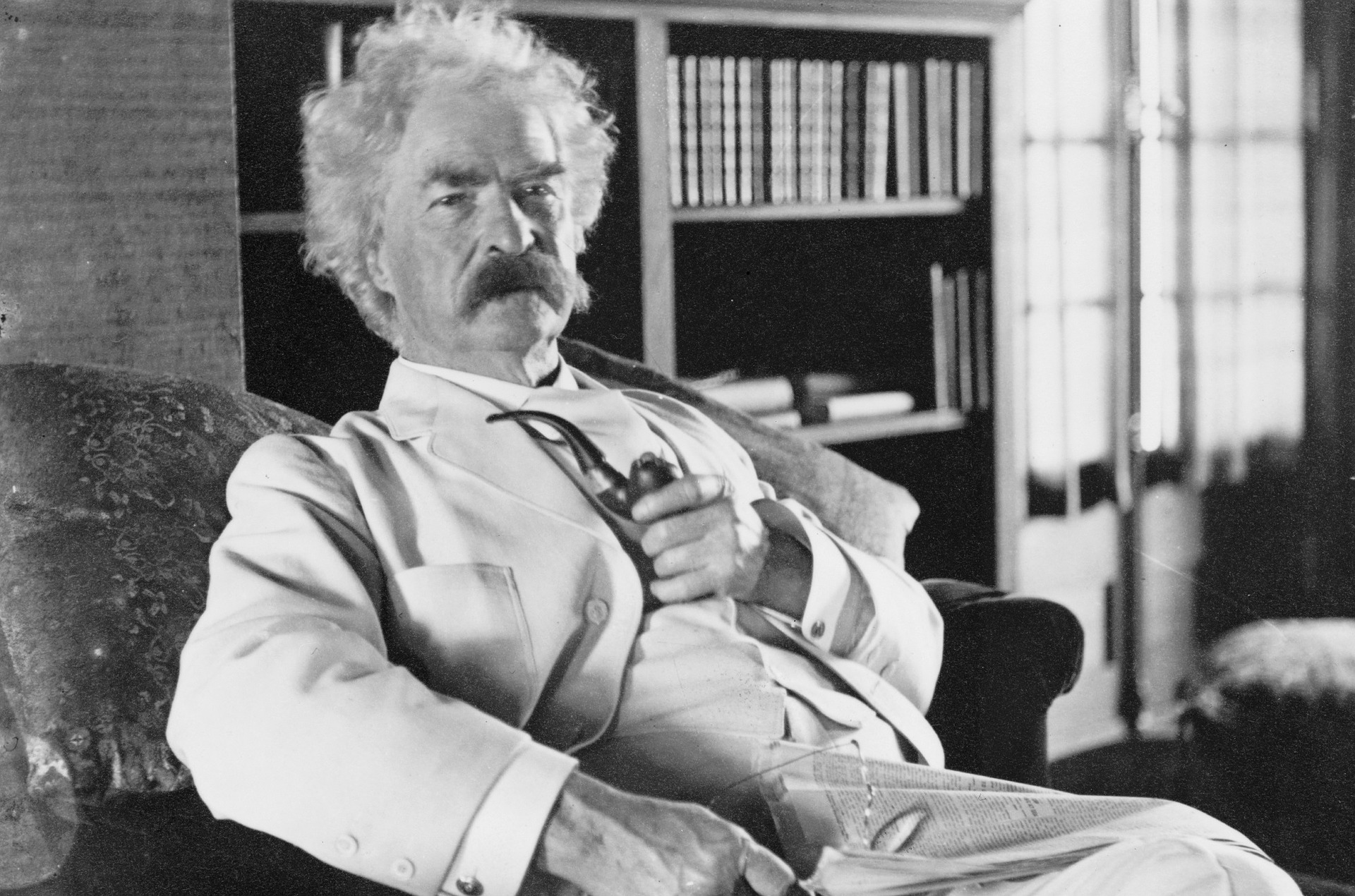

The Folklore of Cornwall by Ronald M. James

Ronald M. James’ latest book, The Folklore of Cornwall, has just been released, and is now available

from The University of Exeter Press.

“By considering the folklore of Cornwall in a Northern European context, this book casts light on a treasury of often-ignored traditions. Folklore studies internationally have long considered Celtic material, but scholars have tended to overlook Cornwall’s collections. The Folklore of Cornwall fills this gap, placing neglected stories on a par with those from other regions where Celtic languages have deep roots. The Folklore of Cornwall demonstrates that Cornwall has a distinct body of oral tradition, even when examining legends and folktales that also appear elsewhere. The way in which Cornish droll tellers achieved this unique pattern is remarkable; with the publication of this book, it becomes possible for folklorists to look to the peninsula beyond the River Tamar for insight. A very readable text with popular appeal, this book serves as an introduction to folklore studies for the novice while also offering an alternative means to consider Cornish studies for advanced scholars. The comparative analysis combined with an innovative method of The Folklore of Cornwall is not to be found in other treatments of the subject.”

Recommended Books from #FolkloreThursday

References & Further Reading

William Bottrell, Traditions and Hearthside Stories of West Cornwall (Penzance: W. Cornish, 1870, first series).

———-, Traditions and Hearthside Stories of West Cornwall (Penzance: Beare and Son, 1873, second series).

———-, Stories and Folk-Lore of West Cornwall (Penzance: F. Rodda, 1880).

Robert Hunt, Popular Romances of the West of England or the Drolls, Traditions, and Superstitions of Old Cornwall (London: Chatto and Windus, 1903, combined first and second series [1865]).

Ronald M James, The Folklore of Cornwall: The Oral Tradition of a Celtic Nation (Exeter: University of Exeter Press, 2018).