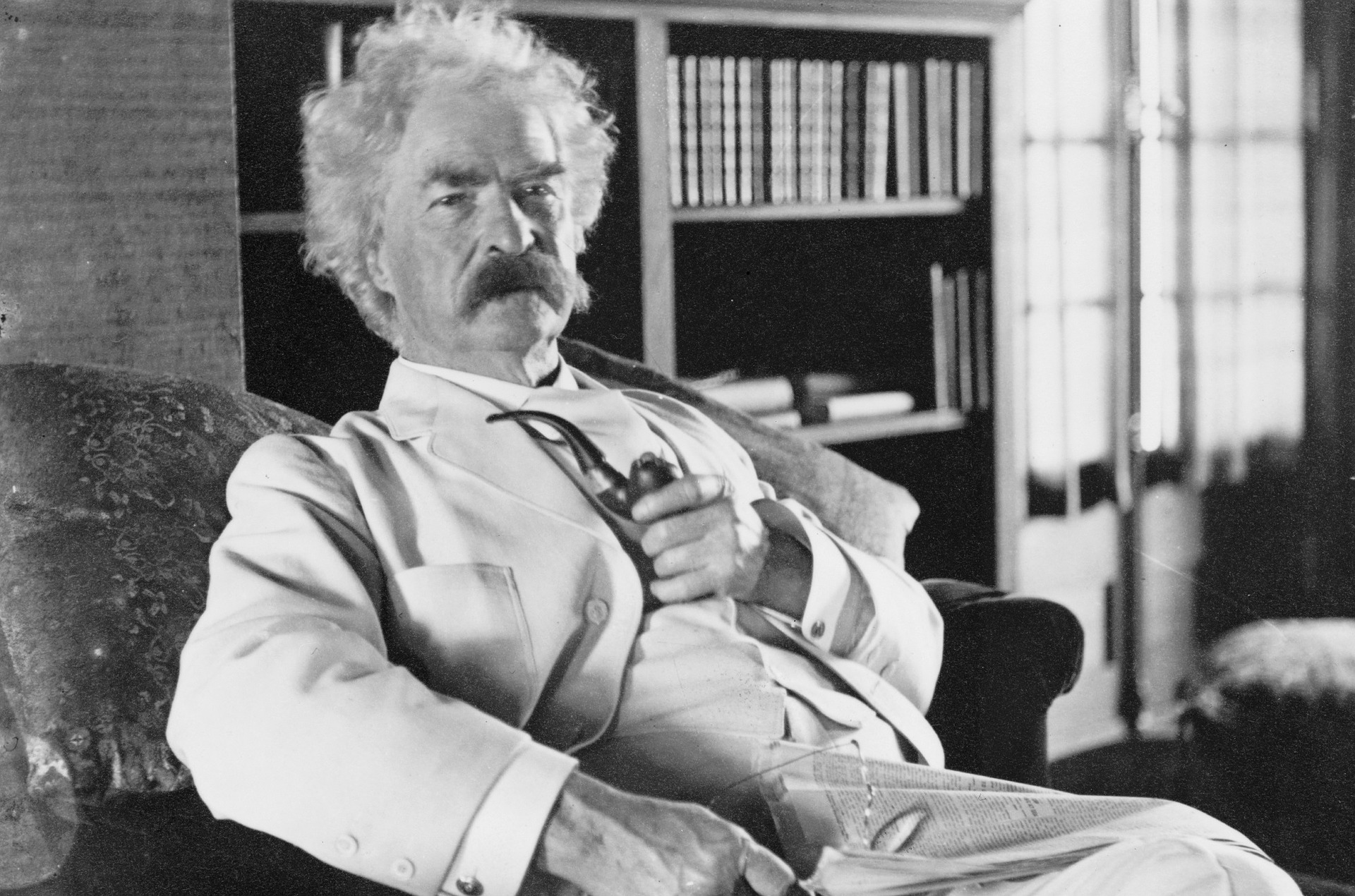

In a daring act, facing frightful peril, Mark Twain exploited a legend to launch his onstage comic career. With his future as a lecturer on a knife’s edge, Twain decided to open with a worn-out narrative that had seen better days. A disgruntled audience nearly drove him from the stage … until they understood his brilliant manipulation of their own folklore.

Twain recounted an event from 1859: Horace Greeley (1811-1872) was a renowned New York journalist credited with the quip, ‘Go West Young Man!’ To see the region he advocated, Greeley travelled beyond the reaches of civilization and found himself in the Sierra Nevada foothills, needing to cross the summit to reach Placerville, California to give a speech that evening. He engaged a stage company for quick passage and was placed in the care of Hank Monk (1826-1883).

The steep ascent required unhurried progress, but the expert teamster understood that a gallop down the other side would make up for lost time. For the demanding Easterner, unaccustomed to dramatic escarpments, progress seemed too slow, and he repeatedly called for more speed. To this, the laconic hero of the legend assured Greeley that they would get there on time. And then he slowed the horses even more.

When they finally reached the summit, Monk turned his team loose for a rousing sprint down the steep slope, careening past cliff faces with death-defying turns. Terrified, Greeley now pleaded for a slower pace, but Monk yelled back, ‘Hang on, Horace, I’ll get you there on time’, which of course they did, but it was a humbled, dishevelled Eastern elitist who arrived. The celebration of a trickster in the West’s wild terrain with an Eastern notable as the brunt of a joke fuelled the narrative’s success in local folklore.

The story quickly became part of Western tradition and it soon appeared in print as well. Samuel Clemens (who would become ‘Mark Twain’) repeatedly heard the legend of ‘Horace Greeley and the Stagecoach Driver’ when travelling to the American West in 1861. The anecdote suited Twain’s brand of wit, but before he could put ink to paper, someone else recognized its value.

Charles Farrar Browne (1834-1867) writing as Artemus Ward brought Greeley’s story to a national audience in 1865. America’s favourite comic, Ward wrote popular newspaper columns, then published a volume titled His Book, and finally became one of the first stand-up comedians. In 1863, Ward went West to perform and to write his next book, His Travels, in which he told the account of Greeley and Monk without adornment.

Because of Browne’s fame, Greeley’s unflattering role in the Western legend became nationally known. When Greeley ran for the White House in 1872, seeking to defeat incumbent President Ulysses S. Grant, the story of Greeley’s humiliation in Hank Monk’s stagecoach was read on the floor of the House of Representatives, inspiring Eastern newspapers to repeat it. The story helped characterise the effete intellectual as ill-suited to replace a heroic Civil War general. Grant soundly defeated Greeley in the election.

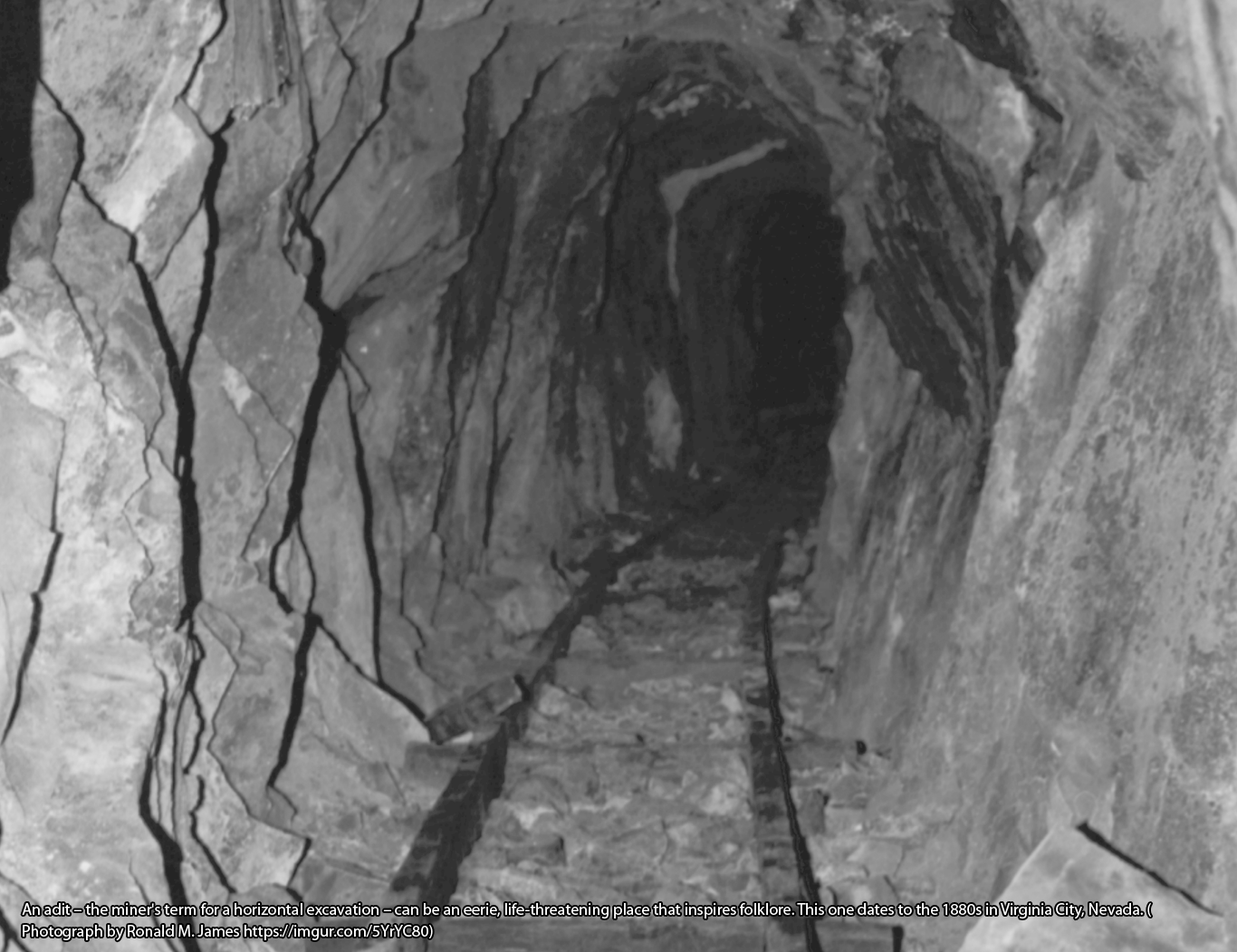

During Ward’s Western sojourn, he met Twain, working as a reporter in Virginia City, Nevada. Recognizing Twain’s talent, Ward helped publish his first breakout piece – ‘The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County’. Ward counselled Twain to leave journalism to pursue lecturing and writing books. Twain followed the advice, but initially he laboured under Ward’s shadow.

The story of Horace Greeley, so widely circulated in regional folklore, gave Twain an opportunity to demonstrate his abilities. He stepped out of the frame, providing a ‘meta’ twist: folklorists Michael Dylan Foster and Jeffrey A. Tolbert refer to this sort of thing as the folkloresque, a term describing a variety of folklore manifestations and folklore-like inventions. Twain decided to focus on how the truly great story of Greeley and Monk had worn out its welcome. In 1866, Twain took to the stage in San Francisco, using the occasion to stretch oral tradition to his own purposes.

He later recalled that among the hundreds attending were many friends, and he set out to ‘grieve them, disappoint them, and make them sick at heart to hear me fetch out that odious anecdote with the air of a person who thought it new and good’ (Clemens 2013: 200). He told the legend, which by then all Westerns had heard repeatedly. As he recalled,

I told it in … a colorless and monotonous way, … and succeeded in making it dreary and stupid to the limit. Then I paused and looked very much pleased with myself, and as if I expected a burst of laughter. Of course there was no laughter, nor anything resembling it. There was a dead silence. As far as the eye could reach that sea of faces was a sorrow to look upon; some bore an insulted look; some exhibited resentment, my friends and acquaintances looked ashamed…

I tried to look embarrassed, and did it very well. For a while I … stood fumbling with my hands in a sort of mute appeal … for compassion. Many did pity me – I could see it. But I could also see that the rest were thirsting for blood. I presently began again, and stammered awkwardly along with some more details of the overland trip. Then I began to work up toward my anecdote again with the air of a person who thinks he did not tell it well the first time … The house perceived [this] …, and its indignation was very apparent (Clemens 2013: 200-1).

Twain told the legend a second time and recalled a house ‘as still as a tomb.’ He repeated his performance of dismay, then he resumed the account of his journey across the continent, making it clear he intended a third run at the story. As Twain described in his autobiography, suddenly, ‘the front ranks recognized the sell, and broke into a laugh. It spread back, and back, and back, to the furthest verge of the place; then swept forward again, … and at the end of a minute the laughter was as … thunderously noisy as a tempest.’ Twain’s relief was profound since his commitment to ‘working a delicate piece of satire’, required repetition of the story until the audience finally understood the joke.

From all of this, there is insight into a Western legend that thrived in the early 1860s and then disappeared from the region’s folklore. At the same time, we can ask why legends elsewhere were told for centuries and yet this narrative became tedious within a few years. The answer, it seems, anticipates a characteristic of the modern urban legend: a savvy, literate populace can find itself quickly exposed to a clever story in diverse media, in this case, orally, in print, and then on stage.

The modern audience demands innovation and scorns repetition. Ironically, post-modern oral tradition constantly regenerates as it sheds ‘tradition’ in favour of the new. The folk now scorns anything worn thin. Twain recognized this even when the more famous Artemus Ward did not, and it was because of the genius that could turn a legend into the folkloresque that Twain became immortal while Ward is largely forgotten.

Recommended Books from #FolkloreThursday

References & Further Reading

Clemens, Samuel [Mark Twain]. 1993 [1872]. Roughing It, Harriet Elinor Smith and Edgar Marquess Branch, eds. Berkeley: University of California Press.

———-. 2013. Autobiography of Mark Twain, Volume 2, Benjamin Griffin and Harriet Elinor Smith, eds. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Foster, Michael Dylan and Jeffrey A. Tolbert, eds. 2016. The Folkloresque: Reframing Folklore in a Popular Culture World. Logan: Utah State University Press.

James, Ronald M. Summer 2017. “Monk, Greeley, Ward, and Twain: The Folkloresque of a Western Legend,” Western Folklore, 76:3.

Pullen, John J. 1983. Comic Relief: The Life and Laughter of Artemus Ward, 1834-1867. Hamden, Connecticut: Archon Press.

Ward, Artemus. 1865. Artemus Ward (His Travels) Among the Mormons, E. P. Hingston ed. London: John Camden Hotten.