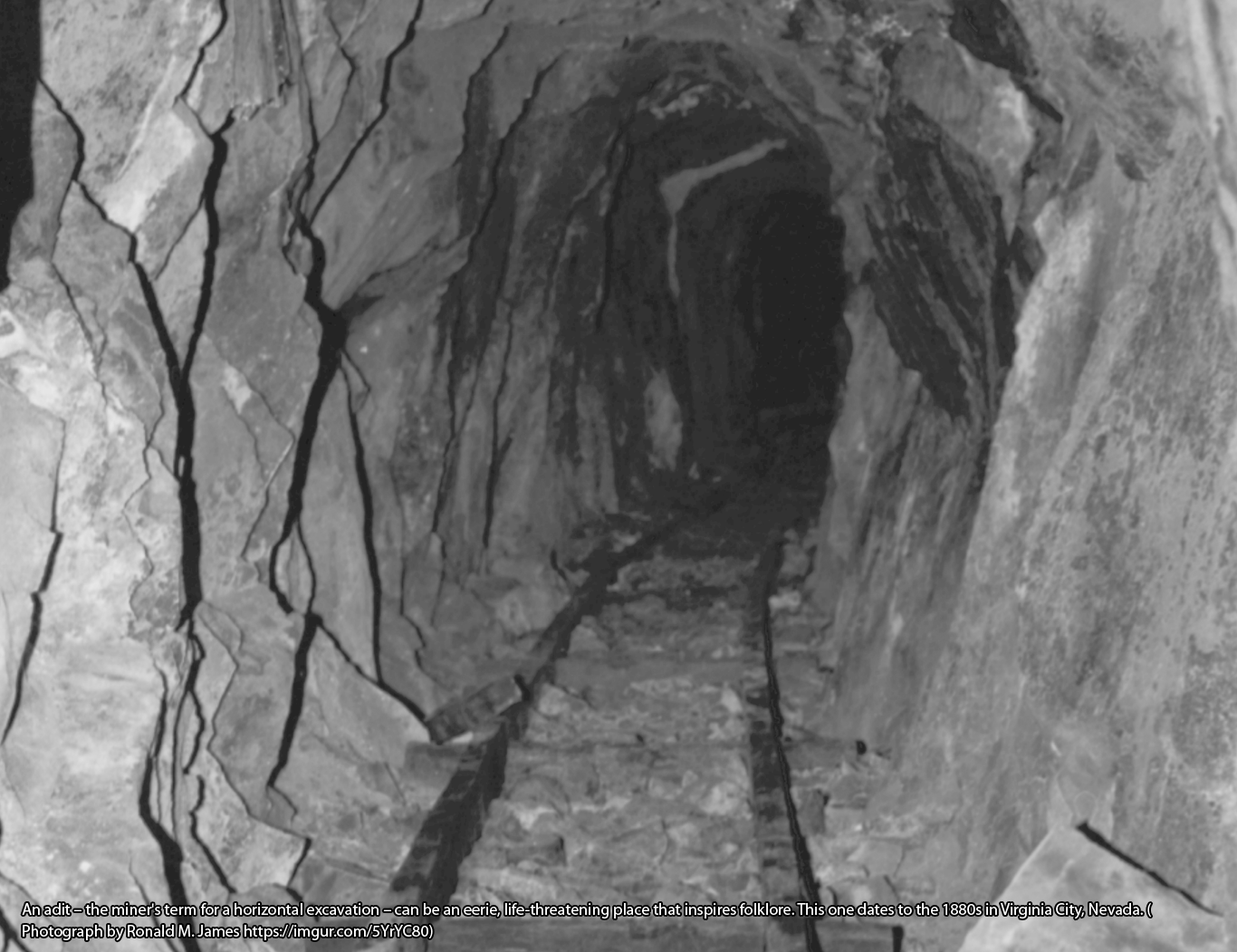

Walking deep into a mine, when the last gleam of sunlight is eclipsed by the next turn, reveals the overwhelming weight of being underground. When all signs of the outside world are gone, the bulk of the mountain above seems even more menacing as it threatens to crush the wooden supports that keep miners alive. The terrifying danger of the subterranean world echoes with every drip of water, every creak of timber, and every pebble shifting within the excavation.

Being underground is unnatural, and mines consequently inspire a rich body of folklore. Traditions fluoresce, no doubt, because peril coincides with wealth. At the same time, while worker’s folklore was and is shared exclusively by miners, there are also community beliefs and narratives about the industry. My #FolkloreThursday post, ‘Lost Mines and the Secret of Getting Rich Quick‘, fits both categories: miners and non-miners both tell stories about riches found and then lost.

The nineteenth-century international mining frontier attracted workers from throughout the world, and they borrowed folklore from one another. Specific traditions were associated with surface placer mines, made famous by the California Gold Rush of 1849. It was considered lucky, for example, to have an African American at an excavation. The technology of surface mining followed centuries-old folk practices. At the same time, word of innovations, itself a form of folklore, spread up and down the expansive mining West.

Folklore was even more central to underground excavations. The chance to discover rich, concentrated deposits encased in rock captured the imagination, and ever-present dangers helped proliferate industrial traditions. Underground excavations also accentuated the division separating miners and non-mining members of the community: workers underground had their own folklore, and townspeople above had distinct beliefs and stories about the industry.

William Wright, a nineteenth-century journalist of the mining frontier, published numerous accounts that drew from oral tradition. Writing with the nom de plume, Dan De Quille, Wright’s book, The Big Bonanza (1876) about Virginia City, Nevada, hints at the diversity of stories that mining inspires.

Faced with the ever-present threat of injury and death, miners often told stories about and took precautions against disaster. As De Quille pointed out: ‘So many men have been killed in all of the principal mines that there is hardly a mine … that does not contain ghosts, if we are to believe what the miners say.’ Because of the danger, mining folklore often involves ways to keep safe. Underground rats, for example, were thought to bring good luck, so they were fed and allowed to go unharmed. This may have also been functional, since rats fleeing an excavation could be an indication of impending disaster.

Similarly, many miners throughout the world believed that supernatural workers shared their excavations. The Cornish knockers are one variety of this common theme, but while they were specific to Cornwall, they became widespread: because of their international prestige, Cornish miners lent the industry their vocabulary, their technology, and their traditions about the knockers. While emigrant folklore typically vanishes with the passing of a first generation, the Cornish knocker became a fixture of early modern mining folklore in North America, shared by workers regardless of ancestry. As a result, knockers transformed into the North American tommyknockers, entities that shifted between elf and ghost and are more recently celebrated by the entire West, whether by miners or others.

Other traditions exclusive to workers include a fear of whistling underground. For some miners, encountering a redheaded woman when reporting for work was considered a bad omen. At the same time, light-hearted stories about pranks became favorites among workers.

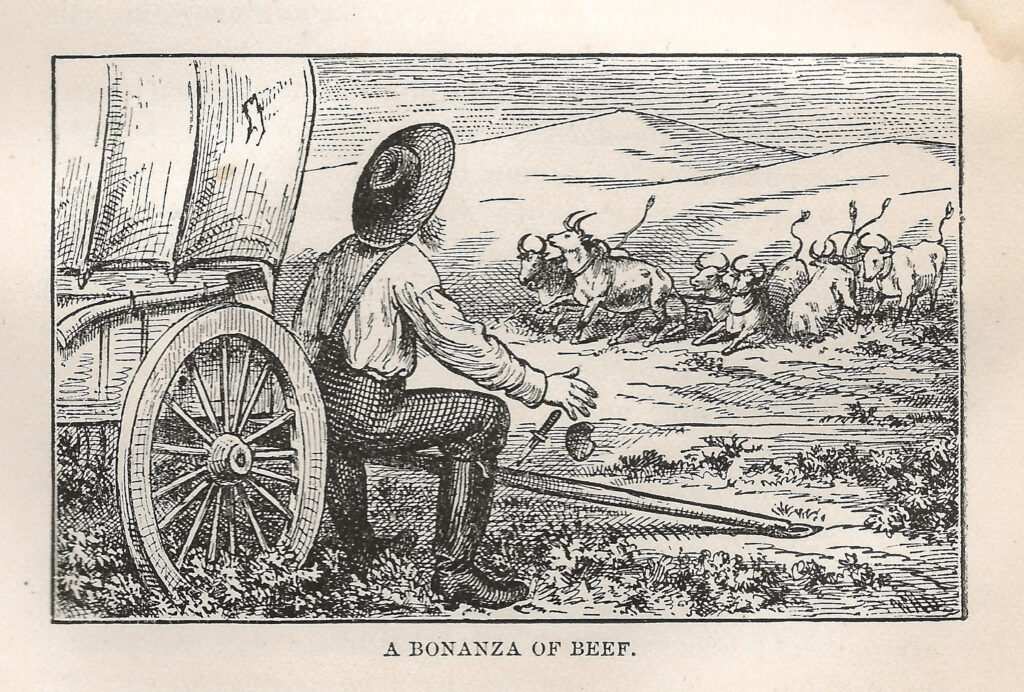

De Quille’s record of folklore held in common by the larger community often focuses on the danger of living near industry. One account describes a teamster who had unhitched his oxen from a wagon so they could graze.

[They were still] fastened together … by a heavy log chain that passed through their several yokes… In picking along they reached an old shaft, round which those on the lead had passed; then, moving forward, had so straightened the line as to pull a middle yoke into the mouth of the shaft. All then followed, going down like links of sausage. The shaft was three hundred feet in depth, and that bonanza of beef still remains unworked at its bottom.

Stories of accidents above and below ground, even those that really happened, become traditional as people repeatedly recounted them. Similarly, noteworthy dances and concerts held in underground chambers became fixtures of community folklore, recalling and celebrating the grand aspects of mining for generations.

The international mining frontier saw people arrive from throughout the world as discoveries of precious metals inspired emigration. Despite the prestige of Cornish miners, they were nevertheless the target of jokes: people ridiculed their seeming inability to use the letter ‘h’ correctly. While it was absent in phrases such as ‘What ‘appened to ‘im?’, the Cornish were also chided for employing an ‘h’ where it did not belong. A joke printed in De Quille’s Territorial Enterprise described a Cornishman asking an American if he could guess the three fruits in his lunch pail, all of which began with the letter ‘h’. The American could not guess, so the Cornishman revealed that they were ‘a happle, a horange, and a hapricot.’

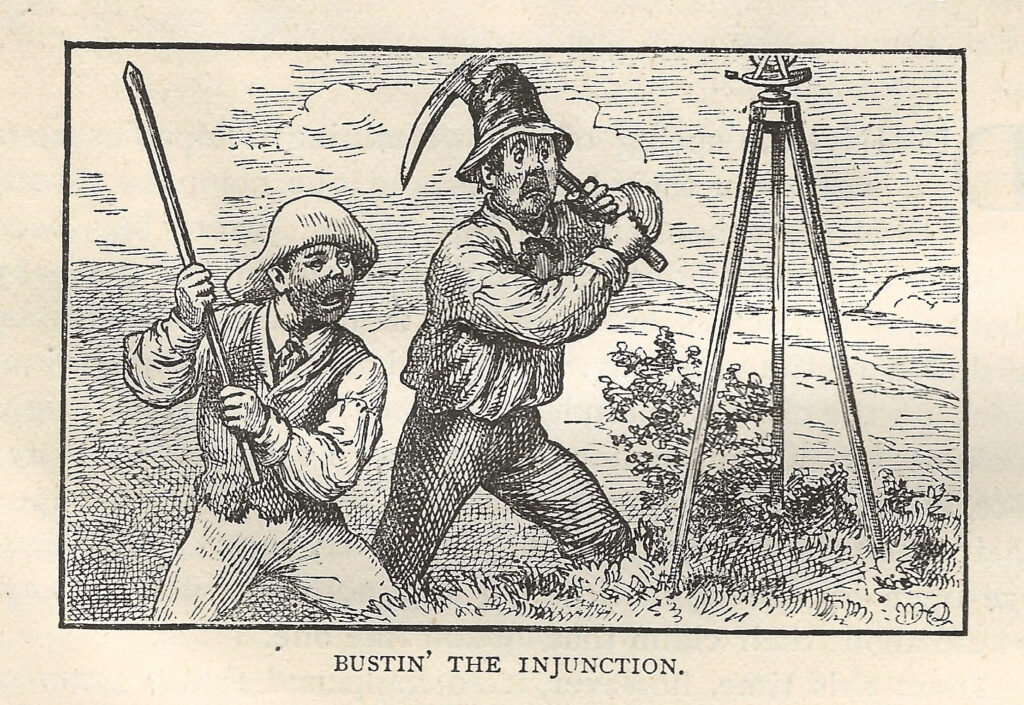

Narratives about other immigrants could be more meanspirited. Many despised the newly arriving Irish, seen by many as poor additions to the American experiment. De Quille published a ‘Pat and Mike’ story that featured two Irish miners who became unemployed because a judicial injunction stopped work on an excavation until the owners could properly survey the property boundary and ‘bust the injunction’. Walking home, Pat and Mike encountered a costly piece of survey equipment near the mine, and they concluded (expressed in a cruel mockery of their Irish dialect to underscore their perceived stupidity) that the example of sophisticated technology was in fact, the guilty party, the injunction that prevented work. They consequently attacked it with mining tools and succeeded in ‘bustin’ up the injunction’.

Immigrant stories and jokes were part of the community reaction to the diverse people drawn together in remote locations by the discovery of mineral wealth. Hurtful accounts are not unique to North America or to mining, but the industry created an environment that cultivated these traditions. With this in mind, American folklorist Richard Dorson published a book on immigrant stories in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula and its copper mines. But he was not alone: folklorists throughout the mining West of North America documented similar traditions. These were the nineteenth-century iteration of the persistent belief that the most recent emigrants will never become ‘proper’ Americans (even though they always do!)

For centuries, mines have been home to an international array of labor lore, traditions shared exclusively by workers. At the same time, mining inspires folklore for those who live near the industry. The results are complex layers of stories and beliefs, each of which warrant exploration.

Recommended Reading from #FolkloreThursday

References & Further Reading

Agricola, Georgius, De Re Metallica, translated by Herbert Clark Hoover and Lou Henry Hoover (New York: Dover Publication, 1950; first published in translation, London: The Mining Magazine, 1912; page numbers refer to 1950 edition [1556]).

Dorson, Richard, Bloodstoppers and Bearwalkers: Folk Traditions of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1952; reprinted, Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2008).

Hand, Wayland D., ‘California Miners Folklore: Below Ground’, California Folklore Quarterly, 1 (1942), pp. 127–53.

———-, ‘The Folklore, Customs, and Traditions of the Butte Miner’, California Folklore Quarterly, 7 (1946), pp. 1–25.

James, Ronald M., The Folklore of Cornwall: The Oral Tradition of a Celtic Nation (Exeter: University of Exeter Press, 2018)

Wright, William (Dan De Quille), The Big Bonanza: An Authentic Account of the Discovery, History, and working of the World-Renowned Comstock lode of Nevada (Hartford, Connecticut: American Publishing Company, 1876).