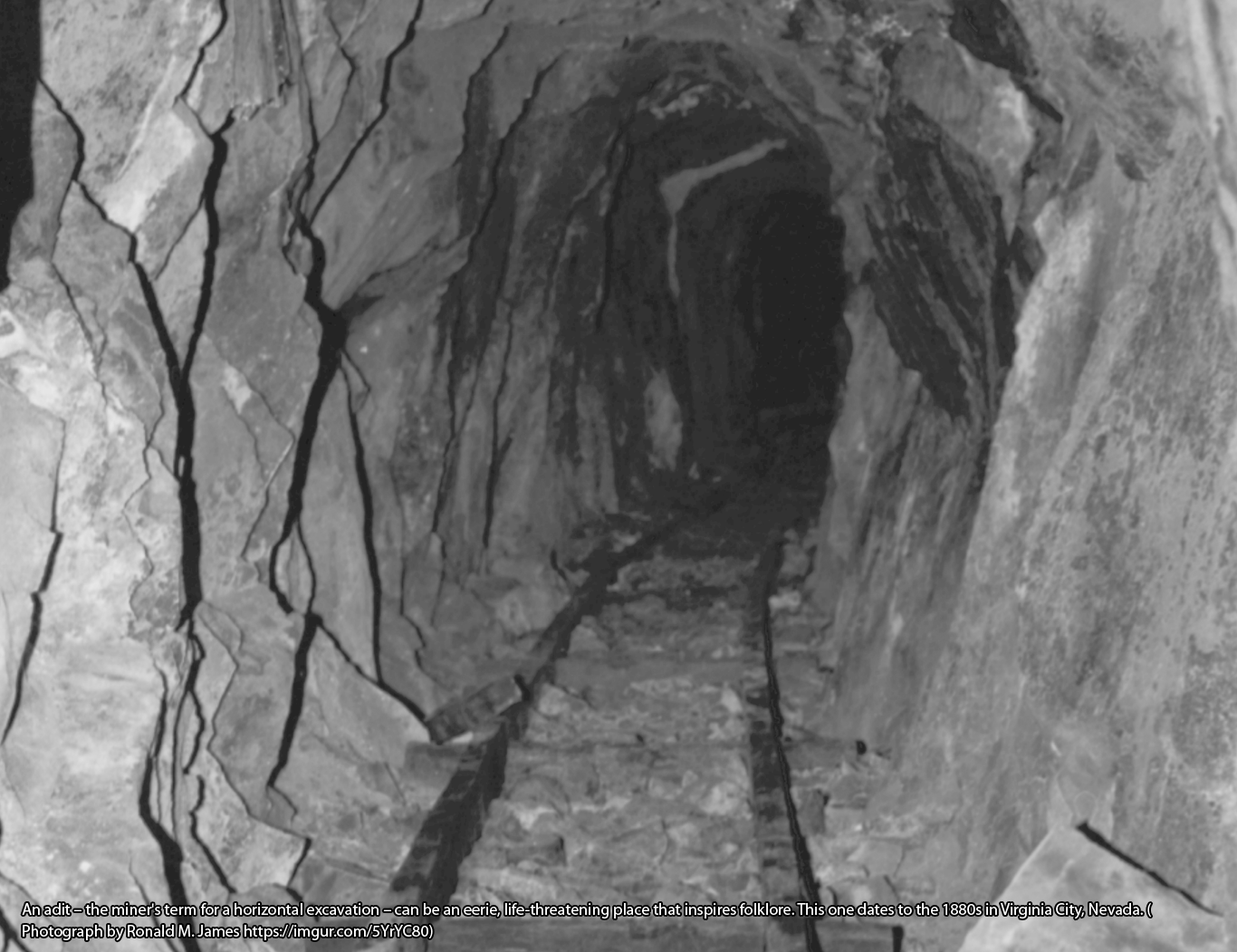

In the summer of 1960 at the age of five, I joined an honored folk tradition by telling my first Comstock lie. It was about a sex worker who had transformed into a legend of the Wild West.

Twenty-five years earlier, George Lyman published a book about the glory days of Virginia City and the great Comstock Lode, a Nevada mining district of extraordinary riches. He described an epidemic in 1859 and how a caring woman, a sex worker named Julia Bulette,

… turned her palace into a hospital. Caldrons of broth and steamers of rice stewed on her stove. Night and day she went from bed to bed in cabin and tent on her mission of mercy, soothing and comforting, feeding and nursing like a white angel.

Gosh what a gal, to use the day’s vernacular. Proving how remarkable she truly was, Bulette accomplished all this, four years before she even arrived on the scene! Not to mention that there was no epidemic.

Bulette came to Virginia City in 1863, one of dozens of sex workers from California. Most faded in the historical record and were ignored in local folklore. All except Julia Bulette, who was eventually resurrected in oral tradition.

While still alive, Bulette gained some notoriety as the favorite of Tom Peasley, a popular saloon owner and captain of a volunteer firefighting company, Liberty Engine No. 1. Bulette even became an honorary member, but with Peasley’s death, her fortunes declined.

Although disease dogged Bulette’s steps, a grisly murder extinguished her life. On a cold night in January 1867, she was bludgeoned and then strangled in her two-room crib. It became the best documented part of her existence. Newspapers published details of her death and funeral, and then, the crime receded from public view, replaced with subsequent cycles of news. When Bulette’s estate was probated, her limited assets could not cover her debts.

Tracing the roots of Bulette’s legend is a challenge for want of sources. Several writers – all men – were in positions to remember her, but they gave her barely more than a passing nod: the journalist Alf Doten mentioned her a few unremarkable times in his diary. A year after her murder, he wrote about her newly captured killer. This event was key for Bulette’s story: because a man was tried, and hanged for the killing, the community could revisit the slain sex worker. Despite this, her legacy sputtered. A few years later, Dan De Quille, another journalist, was silent on Bulette when he published a mammoth overview of Virginia City.

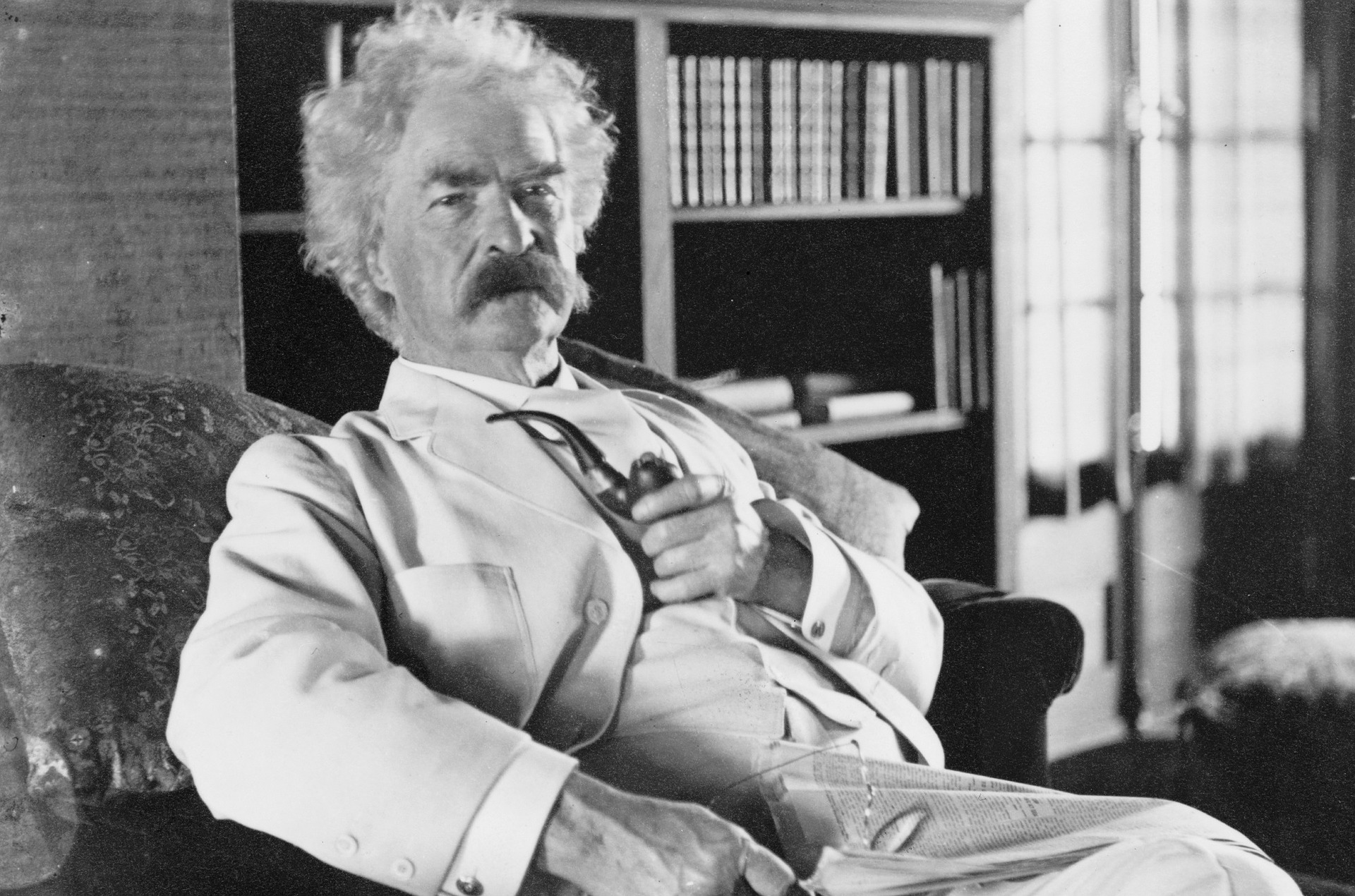

Yet another writer, Samuel Clemens, lived in Virginia City when Bulette arrived, even as he picked his nom de plume, Mark Twain, and yet she is invisible in his Roughing It (1872), the tale of his Western sojourn. In 1868, Twain returned to Virginia City to give a lecture, his visit coinciding with the hanging of Bulette’s murderer. In a column for the Chicago Republican, Twain focused on his repulsion over the execution, but he only wrote of the sex worker in the context of the killer: “He secreted himself under the house of a woman of the town, and in the dead watches of the night, he entered her room, knocked her senseless with a billet of wood …, and strangled her.” So ends Bulette, a nameless, featureless, “woman of the town.”

In 1908, an interviewer asked Virginia City newspaper editor Joe Goodman about Bulette. After more than forty years, Goodman described Bulette with vague, incorrect details. Like others, he fixated on the murder, trial, and hanging – events he knew firsthand. Although Goodman offered no folklore associated with her, the question about the sex worker hinted at oral tradition percolating behind the scenes.

During the twentieth century, the image of Bulette changed. The previously quoted Lyman novel advanced an extravagant image of her, far removed from fact. Bulette had become a madam, elevated to a soiled dove with a heart of gold, wealthy beyond imagination and exhibiting the generosity of a saint. Whether Lyman drew on folklore is impossible to say, but his image of Bulette anticipated later oral tradition.

In 1958, a volume appeared by Zeke Daniels, the penname of local historian Effie Mona Mack, the first woman to take on the Bulette story. Her heroine lived in a palace and rode in a gilded carriage, wearing costly jewelry, and having earned as much – or more – than the richest silver barons of the Comstock.

We do not know when the fabulously conceived Bulette became part of local folklore, but it was in full force by the mid twentieth century even before Mack wrote as Zeke Daniels. In 1945, the Virginia and Truckee Railroad restored a coach-caboose, naming it Julia Bullette, evidence that the long-dead sex worker was winning acclaim in the popular mind.

Beginning in 1949, the American folklorist Duncan Emrich was hot on Bulette’s trail during his many visits to Virginia City. Director of the Library of Congress’s Archive of Folk-Song from 1945-1955, he recorded in a local saloon, documenting aspects of her legend. She was no longer the forgotten, murdered sex worker, a sideshow to a hanging. Bulette had taken center stage in the drama.

All this was happening as Virginia City shifted from mining to tourism. Celebrating local folklore in the 1950s, the owner of the Bucket of Blood Saloon created a fake gravesite for Bulette in the Flowery Hill Cemetery, her actual place of repose long since lost. The community used Flowery Hill until the late 1860s when another cemetery replaced it, leaving the older burial ground to fall into disrepair.

For folklore, however, things were imagined differently. Bulette’s newly created cenotaph resided in a lonely place across the ravine from the respectable cemetery, for now legend maintained that Bulette, shunned in death, could only find eternal rest in the notorious Boot Hill. Her invented grave with its bright white fence could be seen through a coin-operated telescope at the back of the Bucket of Blood. For a nickel, anyone could glimpse the Myth of the Wild West.

This, then, is the setting of my first Comstock lie, uttered in 1960. Inspired by the hit television show, Bonanza, which premiered in 1959, my parents took me and my older brother to Virginia City, the place where the fictional Cartwrights rode into town for supplies, a drink and some trouble.

Tourist were enticed to peer through the coin-operated telescope in the Bucket of Blood Saloon to see the grave of the famed Julia Bulette, who had her own episode in the first season of Bonanza. My father fed a nickel into the device, quickly found the site, and then yielded it to my mother. She, too, saw the gleaming painted wood around Bulette’s memorial, the object of so much mythical awe. Then it was my brother’s turn, who also saw the gravesite.

With my turn, I failed to see anything. The telescope’s timer was clicking down to zero, and we all knew it would shortly go dark, demanding another coin, which my father certainly would not spend. “Do you see it? Do you see it?” my parents repeatedly asked. Seeking to end the harassment, I finally answered, “Yes.” I had lied about the legendary sex worker. Although lacking the artistry of De Quille or Twain, my fabrication was part of a tradition that has contributed to the Myth of the Wild West.

From the mining district’s start in 1859, Comstockers have celebrated tall tales. De Quille called them “quaints,” taking delight when people believed his hoaxes. Twain learned from De Quille, discovering how to turn his own “stretchers” into an art form, a cornerstone of his remarkable literary career. To this day, the folk tradition persists as Virginia City residents attempt to “out stretch” one another when describing the past of their mining district. The process keeps the Wild West a vibrant, ever-expanding domain of folklore.

For decades, speakers of tour trolleys have boomed hourly with tales of this imaginary West, complete with stories about Julia Bulette, now far removed from reality. One can still hear shopkeepers embellishing her legend for eager tourists just as they have done for decades. The process has been unending. A twenty-first-century ghost tour described a local undertaker who refused to yield Bulette’s body, keeping poor Julia on ice for whatever nefarious purpose until he finally yielded the object of his adoration.

In addition, people have recently taken to decorating Bulette’s fictional final resting place with keepsakes. A fake grave fit into local legend has become the object of its own tradition. Folklore thrives.

In 1984, Susan James, my wife, wrote the first real attempt to “bust” the myth of Julia Bulette. At the time, I was concerned: as a historian, I have also corrected the record, colored with the fantastic wanderings of oral tradition. As a folklorist, however, I celebrate imagination. Fortunately, I have repeatedly watched the written word fail to undo legend. Folklore is far more powerful than history.

There was a real, nuanced West of wealth and success, failure and disappointment, filled with people who experienced happiness and sadness, and then exited the stage. In the end, we must not forget that Julia Bulette was a real person whose occupation was too often dangerous and degrading. At the same time, the Myth of the Wild West dominates perception.

Bulette survives with a double life: historians document a woman who thrived in her own way and then was murdered. Popular tradition remembers the Queen of the Red-Light District, a symbol of glorious wealth, living life to its fullest. Virginia City residents and visitors celebrate a legendary life fit into the Mythic Wild West, even as the real Julia Bulette has largely disappeared.

References:

This article adapts a presentation by Ronald M James, given at the virtual conference, “Business as Unusual: Histories of Rupture, Chaos, Revolution, and Change” (September 15-17, 2020), of the subreddit, ‘AskHistorians’.

Daniels, Zeke [Effie Mona Mack]. 1958. Life and Death of Julia C. Bulette: “Queen of the Red Lights”. Virginia City: Lamp Post.

James, Ronald M. 1998. The Roar and the Silence: The History of Virginia City and the Comstock Lode. Reno: University of Nevada Press.

James, Susan. 1998 [September/October 1984]. “Queen of Tarts,” The Historical Nevada Magazine: Outstanding Historical Features from the Pages of Nevada Magazine. Carson City: Nevada Magazine, 47-53.

James, Susan. 2004. “Julia Bulette’s Probate Records,” Uncovering Nevada’s Past: A Primary Source History of the Silver State, edited by John B. Reid and Ronald M. James. Reno: University of Nevada Press, 55-59.

Lyman, George D. 1934. The Saga of the Comstock Lode: Boom Days in Virginia City. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Twain, Mark [Clemens, Samuel]. 1993 [1872]. Roughing It, Harriet Elinor Smith and Edgar Marquess Branch, eds. Berkeley: University of California Press.