Deep in the heart of London, hidden away behind a protective grille, is a stone thousands of people pass by every day without even knowing it’s there. And it could well be the key to keeping the country safe…

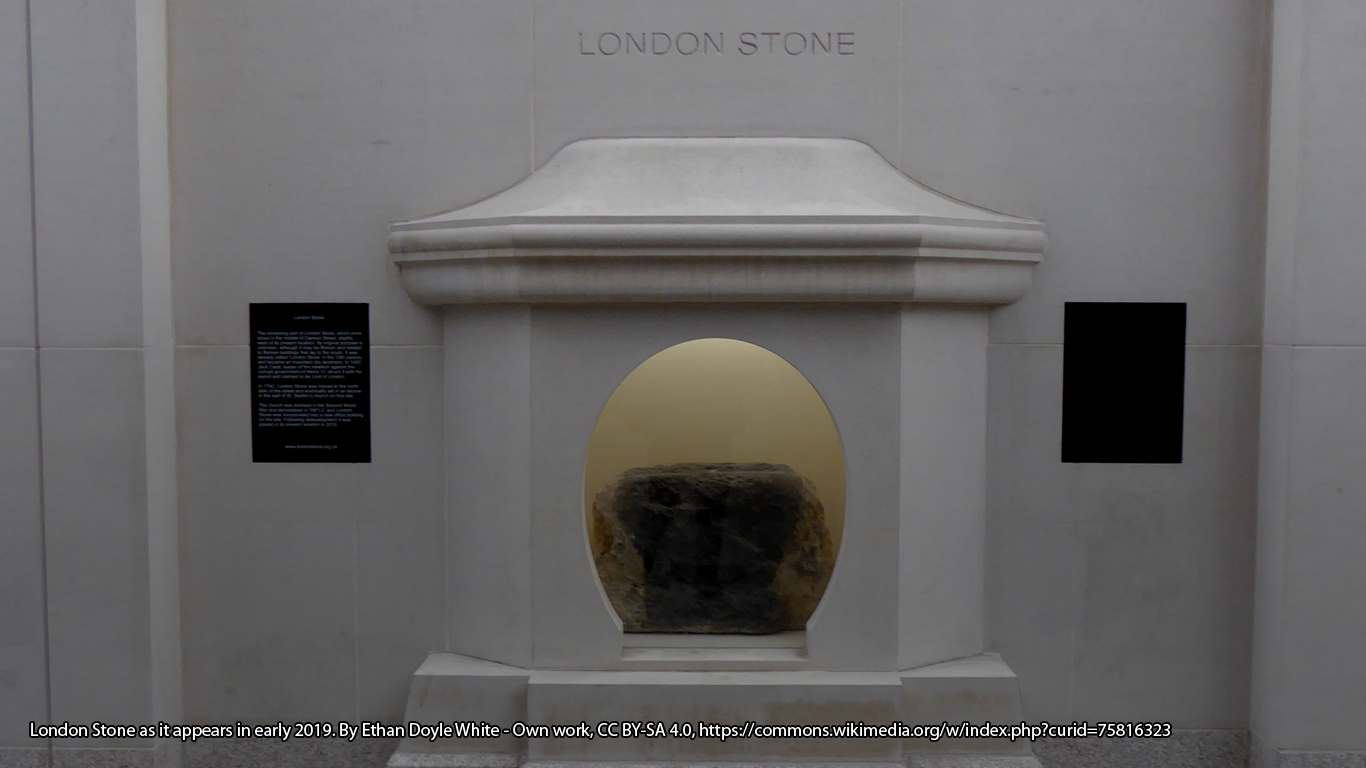

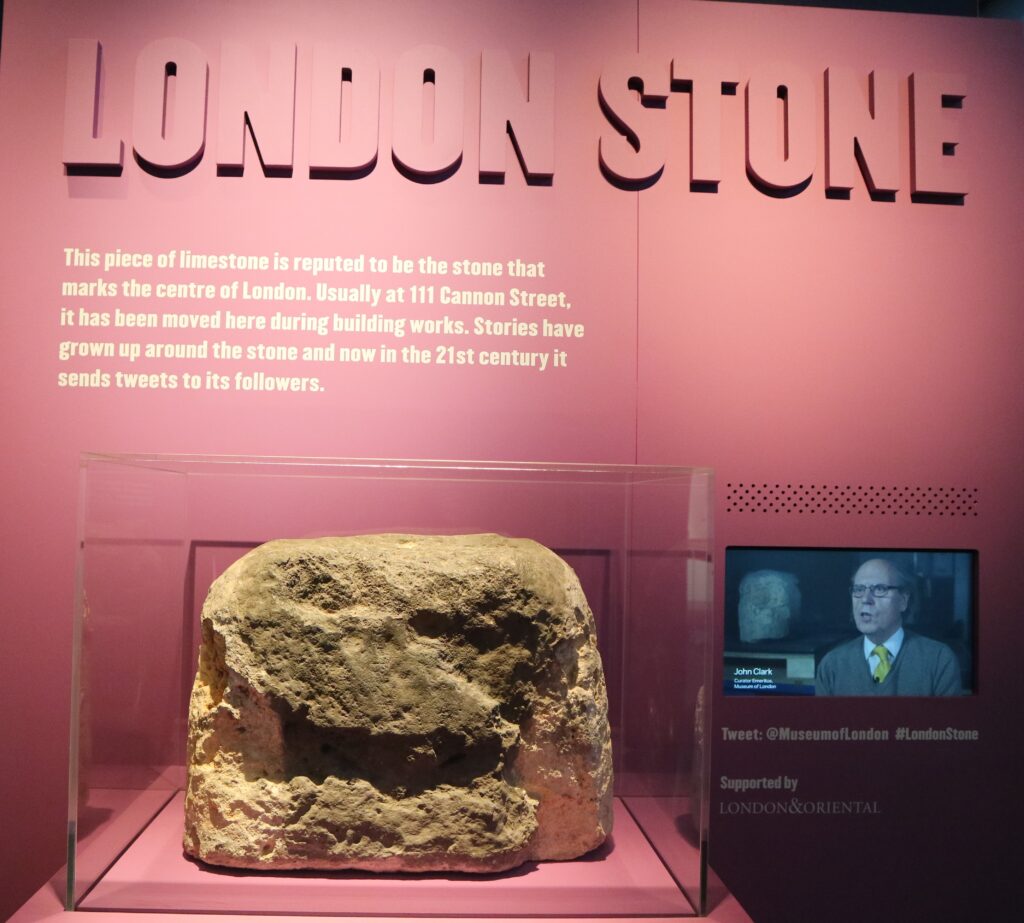

The London Stone is a single block of limestone measuring 53 x 43 x 30cm – about the size of an overnight suitcase. For years, the stone was located behind an iron grille in the wall of a nearby 1960s office block, but when the building was due to be demolished, the stone temporarily relocated to the Museum of London. Before that, it formed part of St Swithin’s Church, and even earlier than that stood alone on the same road. Now it’s housed in a custom-made feature in the wall of Cannon Street in London, easily viewable by anyone walking past.

With written references going back to the 1500s, the London Stone is believed to have existed for centuries before that. In a list of properties belonging to Canterbury Cathedral, there is an entry from around 1100 that refers to a property given to the cathedral by “Eadwaker æt lundene stane” or “Eadwaker at London Stone”. In 1188, there is a further reference to Henry, son of Eylwin de Lundenstane, who became Lord Mayor of London. The Stone is important enough in the history of London that it was even included on the earliest printed map of London from around 1559; just one of a few features other than streets and major buildings to be considered worth naming. Around this time, there was more to the stone, at least physically; it stood three feet high, two feet wide and a foot thick – and that was only the parts of it visible above ground.

But despite these early references, and the later evidence of its existence, no one really knows when the stone first appeared, or what its purpose was.

Jack Cade Becomes ‘Lord of the City’

In 1450, when Jack Cade, the leader of a rebellion against Henry VI’s corrupt government, entered the city of London, he apparently struck the stone with his sword, claiming to be ‘lord of the city’. No one knows why Cade chose to do this – no one had ever done anything similar previously – but the event is dramatised in Shakespeare’s Henry VI Part 2. This appearance includes Cade sitting on the stone as if on a throne, passing judgment on a man who offends him.

There are said to be two indentations on the top of the stone, which some believe to have been made by Cade’s sword.

Roman Milestone, Druidic Sacrifice or Mark-Stone?

In 1586, William Camden, author of the historical, archaeological and topographical description of Britain known as Britannia, offered his own hypothesis on the purpose of the Stone. He believed it was a Roman milliarium – the central milestone from which distances in Britain were measured. While there is no evidence to support this idea, it’s still accepted by people today.

Years later, in 1720, John Strype suggested his own purpose for the stone – that it was ‘an object or monument of heathen worship’ erected by the Druids. Again, there is no evidence of this, but it is another widely-believed idea.

The stone has also been identified as a ley line marker on several different ley lines in. Some fear that the stone’s removal from its original location has violated the integrity of the ‘sacred geometry’ of the city.

Protector of London

By the end of the 18th century, the idea that the Stone was directly linked to the wellbeing of London itself began to take roots. This may have been based on the idea of the statue of Pallas Athene that was said to protect the city of Troy.

A so-called ‘ancient’ saying contributed to this idea.

“So long as the Stone of Brutus is safe, so long with London flourish.”

The saying is part of a supposed legend that Brutus of Troy, who first founded London, brought the stone with him from Troy and erected it as an altar to Diana. The legend continues by claiming that the ancient kings of Britain had sworn their oaths upon it.

However, this ‘legend’ first appeared in a book by the Rev. Richard Williams Morgan in 1857, where he accepted as fact several stories that had no historical precedence. No other historian had ever heard of this story before, and it’s now believed that Morgan made up the saying himself, even though it’s often still quoted as if it was authentic.

John Dee and King Arthur

There are two additional, very recent, legends surrounding the stone. The first is that Dr John Dee, the famous astrologer and occultist, lived close to the stone and chipped pieces of it off for his own experiments. The second legend is that the stone is the same one from which King Arthur pulled the sword that made him king.

Both of these legends first appeared on the website H2G2 with no evidential sources, and have possibly evolved from pieces of fiction.

Guardians of the Stone

Another modern myth about the stone is that the Lord Mayor of London serves as a guardian for it. In 2006, the manager of a sports shop believed that he might be the newest protector. The building that housed the stone changed hands many times, but when the manager of the Sportec sports shop stopped builders from accidentally taking a chisel to the stone, he felt a kinship with it. “I’m not into hocus pocus, but there is something about this stone. For some reason it’s been kept, there’s something special about it.”

Unfortunately, until 1972, when the stone was officially listed as a structure of special historic interest, neither the Corporation of the City of London nor the Lord Mayor seems to have taken any interest in it at all. Ownership of the stone itself passes with the ownership of the land it stands on.

While the purpose of the stone might remain unknown, its symbolic importance can’t be denied. And whether the legends are true or not, maybe it’s prudent to make sure the stone remains in place for a while… just to be on the safe side.

References and Further Reading

- h2g2: ‘The London Stone’

- Museum of London: ‘London Stone in seven strange myths’

- BBC Magazine: ‘London’s heart of stone’

- Clark, John (2007). “Jack Cade at London Stone”(PDF). Transactions of London and Middlesex Archaeological Society.

- Clark, John (11 January 2017). “London Stone: History and Myth”. academia.edu

- Roud, Steve (1998). London Lore: The Legends and Traditions of the World’s Most Vibrant City.