Although their origins lie in Japanese folk traditions, omamori are still a popular sight throughout Japan. The word itself, 御守り, doesn’t have a direct translation into English, but they are protection charms – usually for sale within both Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines – which are said to contain spirits.

Omamori are a combination of the Buddhist tradition of amulets and the charms used in Shintoism. Priests believed they could put the power and strength of the gods into pocket-sized blessings to keep people safe, and through the power of ritual, they created these small objects to hand out. Yanagita Kunio, a Japanese scholar considered to be the ‘father of Japanese native folklorists,’ wrote about the tradition in Japanese Culture in the Meiji Era Tokyo, and said in 1969:

“Japanese have probably always believed in amulets of one kind or another, but the modern printed charms now given out by shrines and temples first became popular in the Tokugawa period or later, and the practice of a person wearing miniature charms is also new. The latter custom is particularly common in cities.”

Each omamori offers a specific form of protection or luck. Possibly the most popular type today is the kōtsū anzen, for traffic safety, and these can often be seen hanging in cars to provide protection for both the driver and the vehicle. Other popular ones include yakuyoke for the avoidance of evil spirits and curses, gakugyō-jōju for education, and enmusubi to help find love. Less commonly, it’s also possible to purchase more specific omamori, such as jōhō anzen kigan for digital security, or even kumajo for protection from bears!

Different types of omamori are believed to be more potent if they come from specific shrines. For example, the enmusubi from Izumo-taisha in Shimane Prefecture is highly sought after, due to the Japanese myth that the kami (gods) meet there every October to determine people’s fates in love for the following year. The liar bird omamori is considered one of the rarest around. It is available only on a specific day each year (25th January) from the Yushima Shrine. It is believed that the bird will take all of your secrets and lies, transforming them into a song of truth and guidance.

Authors Swanger and Takamaya explain in their journal article from Asian Folklore Studies that there is more to an omamori than simply owning it:

“There is no virtue in the mere possession of an omamori. Occasionally a card accompanying the omamori clearly states that its effectiveness partially depends upon the spiritual and moral condition of the recipient.”

As many omamori are worn every day, they often become damaged, and the wear and tear is believed to show the burden it has taken on your behalf. Traditionally they come with an ‘expiration date,’ most often around a year, after which point it should be returned to the shrine it was purchased from to allow it to be disposed of in a sacred fire. However, realistically many people keep them for much longer, and sometimes even pass them down in families.

Swanger and Takamaya suggest that there are two types of omamori: talismanic and morphic.

Talismanic omamori contain words written on paper or wood, usually rectangular in shape, which are then covered in an embroidered bag. The words are usually prayers or portions of a sutra, but in many cases are simply the name of the shrine or temple where they have been purchased. There is one critical rule when it comes to this type of omamori – never open it up. The temptation might be strong to discover the exact wording inside, but by doing this, you will release the blessing stored inside, and lose all of its luck and protection.

Morphic omamori take the shape of an object, and usually don’t have any writing on them. They may look similar to modern phone or bag charms, and are often worn in a similar way. One of the oldest types of these omamori is the hyotan, which is in the shape of a bottle gourd. The hyotan is believed to have many protective qualities, including helping ships to avoid dangers at sea, preventing children and elderly people from falling, and, in many folkloric tales, bringing wealth and prosperity to the owner. In folk medicine, it was also believed that it was possible to transfer a disease to a hyotan.

Today, omamori come in even more forms than they traditionally did. Their ongoing and increasing popularity has led to more commercial manufacturing, and in many cases, omamori can be purchased in souvenir shops. There’s even an omamori vending machine at Zenkoji Temple in Nagano! At the Kanda shrine in Chiyoda, there are sports-related omamori in preparation for the 2020 Olympic Games, and many omamori have mainstream children’s characters on them, such as Hello Kitty, Mickey Mouse and Snoopy.

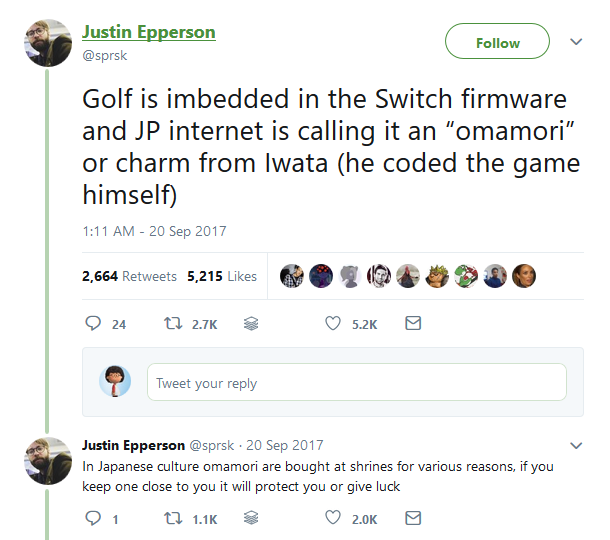

Omamori also have a place in the world of video games, at least as far as some people believe. Last year, a hidden copy of the 1984 NES game Golf was discovered hidden inside the coding for the Nintendo Switch game consoles. While this initially seemed like nothing more than a tribute to a long-beloved game, Justin Epperson, Senior Associate Producer at 8-4 Ltd, who are involved with preparing the device for other countries, discovered something unusual. In the firmware for the Switch, the name given to Golf is ‘omamori’. The original Golf was programmed by Nintendo’s late president Satoru Iwata, who passed away in 2015. Epperson took to Twitter to suggest that Nintendo embedded Iwata’s game as a protection over every unit. Although Nintendo themselves haven’t confirmed or denied this theory, it’s a touching idea that is believed by a lot of people.

There are omamori out there for everyone and almost every situation, to bring good fortune and luck, and to ward away evil. They can help you find love, pass an exam, or even retain your youthful good looks. And yet they only require one thing in return – belief.

References

Kunio, 1969, Japanese Culture in the Meiji Era Tokyo (Vol. 4)

Eugene R. Swanger and K. Peter, Takayama, 1981, A Preliminary Examination of the “Omamori” Phenomenon,Asian Folklore Studies

Natalie Jacobsen, 2015, Japanese Lucky Charms: A Guide to Omamori, Tokyo Weekender