The Mabinogion is a mess of misconstrued mythology, a minefield of mistranslation and misinterpretations. It’s also the font of all fantasy, a literary sub-genre that did not have any following before Lady Charlotte Guest presented her loose translation, first published in seven volumes between 1838 and 1845. Much effort was put into making them read as a cohesive, integrated story, which they were not. They were compiled from many traditional tales told in the Welsh language dating right back to the earliest bardic tradition and originate in an ancient culture that spanned pre-Roman Briton and Eire.

Mabinogi translates as something like, ‘tales of the generations’, with ‘mab’ meaning ‘son’ or ‘child of’. Scholars have since decided that the Mabinogi consist solely of the Pedair Cainc y Mabinogi – the four branches, and it’s those modern scholars who settled on the titles for these four branches, categorising them after the prominent characters in each collection of tales: Pwyll, Branwen, Manawydan and Math. It would be so easy to get bogged down with the scholarly arguments of what is or isn’t canon, but you can find plenty of that elsewhere, so here I’ll focus on just five of my favourite characters to be found in the tales.

It’s a hard choice, as most of them are deeply flawed. For example, Gwydion is often cited as one of the ‘heroes’ and is still a popular name for ‘sons of’ Welsh families to this day. He’s definitely not one of the good guys but some of his exploits are thought to have been appropriated by Merlin in later tellings of the tales. I suppose Gwydion can be respected as an anti-hero, unless you feel unable to cut him any slack after he arranged a war simply so his brother could rape a young maiden? He does get the better of several other major characters and seems to take pride in his lack of honour, winning through lies, guile and magical trickery. Which brings me nicely to Pryderi, who eventually dies at his hands.

Pryderi fab Pwyll is the only character that appears in all four branches of the tales. He’s the son of Pwyll and Rhiannon, King and Queen of Dyfed. This familial triumvirate make up the first three of my five favourite figures from the Mabinogi Tales. Let’s start with mum and dad?

Pwyll Pendefig Dyfed deservedly lends his name to the first branch of the Mabinogi and, for me, his story is the most exciting and would easily pass as a modern fantasy story. Perhaps because it has inspired so many of our contemporary authors.

Whilst hunting for a fabled stag in the Great Greenwood at Glyn Cuch, the young Prince Pwyll is separated from his party when he pursues his pack of hounds as they catch a scent and bound off with zeal. They lead him deeper into the woods and he loses sight of them, following their baying until he becomes confused by what he first takes as echoes before realising that it is not the echo of his own dogs, but the eerie baying of another pack.

On reaching a clearing, he sees that his hounds have chased the stag right into another pack which efficiently takes down the prize. But these rival hunting hounds are unlike those of any neighbouring Lord he knows, and he immediately knows there’s something otherworldly about them. Perhaps it was the way they glowed bright white, or how their ears burned a fiery red. If he had time to think, he would’ve called-off his dogs, but they were so excited they wouldn’t back down and chased the rivals off the kill. As the two packs vied for dominance, Pwyll noticed the shadows across the clearing coalesce into the form of a rider upon an impressive mount.

As this apparition solidified, all the dogs quieted and stillness fell upon the forest. The dark stranger calmly accused Pwyll of interfering with a nobleman’s hunt – a serious crime indeed that could result in execution. Pwyll responded with composure, explaining that, as a fellow nobleman, he understands his accuser’s point of view. The dark lord pushes the point explaining that he is not just any nobleman, but a king. Pwyll responds that he’s also royalty, a chieftain, and asks that he be afforded the courtesy befitting his status.

The stranger then introduces himself as Arawn, a king of Annwn – the Otherworld. He suggests that if Pwyll considers himself of equal status, then he must swap places and rule the Otherworld whilst Arawn takes his place in that human realm. Arawn explains that he desires to live as a mortal to better understand the living. Pwyll realises he has little choice and Arawn magically assumes the form of Pwyll and vice versa. They arrange to meet in the same clearing, one year and a day hence.

They keep their appointment and Arawn reports that Abred, the realm of the living, has been relatively peaceful and he has acted justly in Pwyll’s place. Pwyll reports that it was anything but peaceful in Annwn and that the rival king, Hafgan had tried to take control. Arawn explains that it’s a regular occurrence and that he’s found it impossible to slay Hafgan because any blow against him in combat that does not kill him outright only makes him stronger. “Well, then,” says Pwyll, “it was fortunate that I killed him with the first strike of my sword!”

Arawn is pleased at this news and asks how Pwyll enjoyed the company of his wife. Talk about a loaded question! Pwyll explains that she was excellent company indeed, but although she is by far the most beautiful woman he’d ever seen and she clearly did not know him from Arawn, he didn’t use this deception to his own advantage, “You’ll have to make it up to her on your return!”

Well, Arawn is so impressed with Pwyll’s prowess in battle and honourable conduct with his wife that he says they now share the title, ‘King of Annwn’ and they return to their own lives as firm friends. This is the first magical event in the Mabinogi and this archaetypal motif of crossing between realms is the catalyst for all the magical mayhem to follow…

Pwyll remains haunted by the beauty of Arawn’s wife and finds no mortal woman to match until one day, as he passes a fairy fort, he sees an otherworldly beauty riding out from it, all dressed in shining gold silks and mounted on a bright white mare. He and his men follow but are unable to catch up with her even as their horses gallop and hers never even breaks into a trot. They track her for three whole days. She seems to remain in sight, but just out of reach until Pwyll calls out, begging her to stop so they may talk.

“I thought you’d never ask!” she says with relief, “My horse was getting rather tired! You have chased me for so long and now I’ve caught you!” She explains she’s riding through his realm to avoid an arranged marriage with Gwawl, another from her world, and would be very happy to marry a mortal instead. Pwyll is more than happy to accommodate her wishes and it’s announced that they will be married one year and a day hence.

At the marriage feast, a stranger appears among the guests and asks, as was tradition at a royal wedding, for the king to grant a single request. Pwyll agrees and the stranger pulls back his hood to reveal that he’s Gwawl in disguise and asks for the wedding banquet and all the gifts!

Rhiannon steps in and points out that the feast and gifts have already been given and are no longer Pwyll’s. She says that the only things there that truly belong to Pwyll are her body, soul and devotion. Gwawl says, “Well, they’ll do nicely, then!” Pwyll is furious but Rhiannon convinces him that he’s honour-bound to grant the request. Rhiannon asks that Gwawl return to finally take her as his bride… one year and a day hence.

The day after the year has passed, Gwawl and Rhiannon hold their wedding feast and a stranger turns up and asks that a single request be granted. Gwawl sees through the disguise and agrees to grant any ‘reasonable’ request. Pwyll produces a sack and asks to fill it with food from the feast. Gwawl, wishing to appear generous agrees.

The sack looked plain enough but had been secretly enchanted by Rhiannon so that it can never be filled until a nobleman declares it to be. So, all the food goes in and so do most of the wedding gifts until Gwawl becomes furious. Pwyll suggest that he makes sure the sack is full by treading down the contents, which Gwawl does and declares that it is now full. The sack closes around him.

Pwyll hoists the sack up from the rafters and his men proceed to beat it with sticks until Gwawl pleads to be spared. Before letting Gwawl out, Pwyll makes him promise that he will leave his kingdom and not interfere again. As Gwawl leaves the hall, though, he vows vengeance…

It’s many years after their wedding when Rhiannon eventually bears an heir to Pwyll’s kingdom. Whilst his wife recovers, the king assigns six maids to watch over the baby boy. Inexplicably, all six fall asleep and the baby is abducted. When the maids awake from their enchanted slumber they are so scared that they try to cover their failure by blaming Rhiannon. They beat each other so they have bruises to show and kill an animal for its blood which they smear all over Rhiannon as she lay asleep. They then report that the queen had subdued them with demons and eaten her own child.

Pwyll disbelieves them but cannot find any other explanation to convince his court. He refuses to have Rhiannon put to death and instead allows her to retain her title as queen and to sit at his side for state duties. He sets her the penance of waiting at the castle gates each day to explain what has happened to everyone who comes and goes. This could’ve been a form of punishment, or a way of interrogating a broad cross-section of populace for any news or clues about what really happened to their son…

It isn’t too long before their son is reunited with them, though he has, miraculously, already grown into a strapping young lad. He’s been raised through his express boyhood by Lord Teyrnon Twryf Lliant, who famously reared the most sought-after horses in the lands of Dyfed and Gwent. Inexplicably, the foals of his finest mare always went missing immediately after their birth… Whilst sitting vigil as his mare foaled, he saw a monstrous shadow at the window and as the foal was born a huge claw reached in to snatch it.

This time, Teyrnon was ready and struck the monster a blow with his sword, cutting off its arm. He gave chase, but the mysterious monster had vanished. On his return, instead of the severed arm, he finds a baby boy. Being childless he and his wife decide to raise the child as their own. Okay, that’s really the first inkling we have of just how weird the Mabinogi will get…

Lord Teyrnon and his wife were surprised that the baby grew at a superhuman rate and also at the undeniable resemblance it bore to Pwyll. They put two-and-two together and decide to reunite their adopted son with his rightful parents. Rhiannon is delighted and finally gives her son a name, Pryderi – which doesn’t directly translate, but sounds like words for ‘loss’, ‘delivered’ and ‘care’.

Pryderi is believed to have inherited enviable magical prowess, from his fairy-mother and through the blessings of Arawn upon his father, yet vows to live by mortal means and refuses to employ magic whilst in the realms of men. His rival, Gwydion despises him for this, which brings us back to the aforementioned slaying of Pryderi in the fourth branch. I have recounted that tragic tale previously here but to recap:

Gwydion’s brother, Gilfaethwy, becomes ‘love-sick’ after he sets eyes on their uncle’s beautiful ‘foot-maiden’, Goewin. Their uncle is the great god-chieftain Math fab Mathonwy, who is unable to set foot in our realm unless called forth by the advent of war and usually has his feet supported by two young ladies. So, to help Gilfaethwy get an opportunity to rape the fair Goewin, Gwydion uses magical deception to steal a sounder of sweet-fleshed pigs that had been gifted to Pryderi by Arawn as a symbol of continued gratitude for what his father had done for him… War ensues and after pretending to join the march, Gilfaethwy doubles back to force himself upon Goewin. It’s a long war that results in a series of bloody battles and so many deaths that, finally, Pryderi agrees to meet Gwydion in single combat to decide the outcome. Pryderi, who you may recall has considerable magical powers inherited form his fairy mother and favoured father, still refuses to use his powers and feels honour-bound to fight Gwydion man-to-man. Gwydion is the victor winning by his “strength and valour” …oh, and also by the use of “magic and enchantment.” Cheat!

So, the stories of my first four favourite characters, Pwyll, Rhiannon, Pryderi and Arawn are all bound together in one of the more cohesive sagas in the Mabinogion. I’m not counting the uber-villain, Gwydion in my selection. So, as a ‘modern bard’ myself, my fifth nominee has to be the greatest of all bards, Taliesin, though this may be a controversial choice as some modern Mabinogi scholars do not include his story as ‘canon’.

It seems that the legendary version of Taliesin, may have been inspired by a real C6th poet, but I’m focussing on the folklore here and the story of his birth is one of the more weird and imaginative sequences typical of much of the Mabinogion. It may seem familiar as it it’s been repurposed many times in traditional stories and fairy tales.

My preferred telling starts with the powerful and slightly evil sorceress, Ceridwen, who was so dismayed at her son’s ugliness that she sought to bless him with the poet’s gift so his words would be forever filled with beauty. She had a magic cauldron, called Awen, in which she prepared the elixir of wisdom and inspiration. This was a particularly complicated and dangerous potion to brew. All but the first few drops would be a deadly poison and it had to be continually boiled and stirred for (you guessed it!) one year and a day.

She enlisted an old blind man to feed the fire and her boy servant, Gwion, to do the stirring. On the day that the elixir was ready, Gwion was so tired that he had become a little careless and splashed a few drops from the big stirring spoon. They fell onto his thumb and he sucked it to ease the sudden scald. Whoops! He instantly felt the swelling of wisdom, knowledge and magic within and realised what he had done. Fearing the retribution of Ceridwen, he ran.

After pausing for a moment to beat the old blind man for letting such a thing happen, Ceridwen went after Gwion who was so tired after stirring the soup of inspiration for a year that he was unable to outrun her. As she closed, though, he felt the power of his new gift change him and he became a swift hare. Ceridwen shape-shifted into a hound and was almost upon her quarry when the hare leaped into a river and transformed into a fish. Changing herself into an otter, she followed him into the river, and would have easily caught him had he not jumped out of the water to become a bird. Ceridwen morphed into a hawk and was stooping down to take her prey when the smaller bird seemed to vanish. Gwion has turned into a single grain of wheat and fallen onto a freshly sown field. Ceridwen realising what had happened alighted and turned from hawk to hen to eat her fill of grain. And that was the end of little Gwion. Or was it?

Ceridwen soon found that she had become pregnant and knew the magical seed of Gwion was responsible. She decided to kill the baby when it was born, but when the day came, her maternal instinct had kicked-in and she couldn’t bring herself to do it. Instead, she set the new-born adrift on the sea in a coracle.

This pursuit through different animal forms is a recurring motif in many folktales and has been reworked many times. One version that springs immediately to my mind is the sequence in Disney’s 1963 classic, The Sword in the Stone, in which Merlin battles Mim through a series of animal transformations, and when Mim thinks she’s bested him by becoming a dragon, Merlin changes into a virus and makes her rather poorly. Another is the wonderful sequence in BBC’s 1984 adaptation of The Box of Delights when Herne the Hunter takes young Kay Harker through several combinations of predator-prey pursuit.

So, what was the eventual fate of the baby adrift in a little boat?

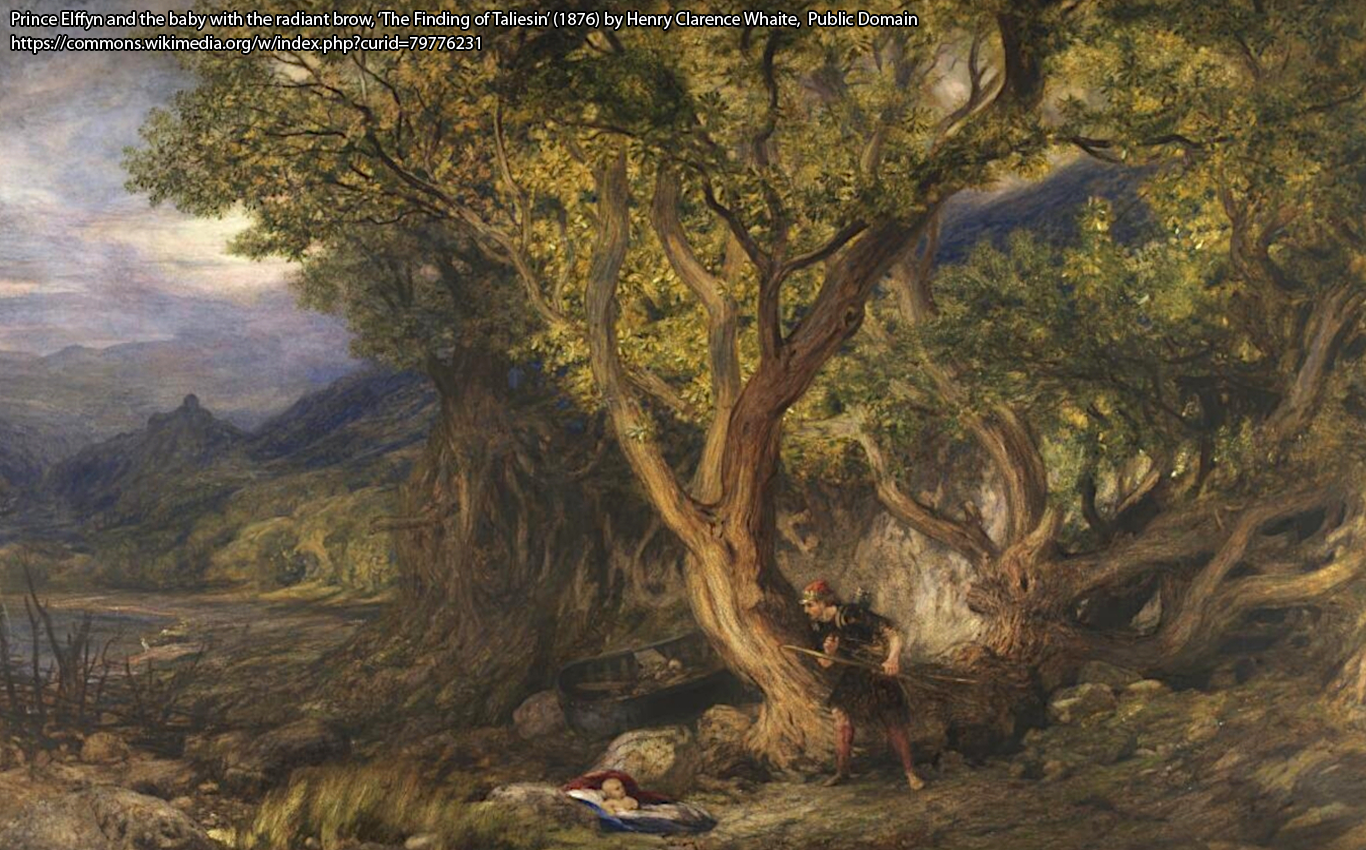

That depends on what sources you might look to. In the version of the ‘Tale of Taliesin’ most often taken to be part of the Mabinogion a luckless prince, Elffyn goes to an enchanted waterfall said to yield treasure on a particular day every year. There, he finds a small boat…

He investigates, hoping for treasure, and for a moment thinks he sees the gleam of gold but that turns out to be the baby’s wet head catching the light of dawn. Elffyn is disappointed that instead of gold, it’s just a ‘radiant brow’, or tal iesin in Welsh. He doesn’t want the burden and extra expense of raising a foundling but, as he walks away, the baby sings a fascinating and gripping tale. The ballad tells his origin story and lists the several forms he had taken so far: fish, frog, crow, roe-deer, wolf, thrush, fox, martin, squirrel, fire, a spear-head, boar and a grain of wheat. Elffyn realises that the baby bard was the treasure he was seeking and raises the boy as his own. Taliesin grew into a beautiful youth and had many magical adventures as well as earning the reputation as the greatest bard and wisest prophet that ever was.

Some commentators draw parallels between the tales of Taliesin and those of Merlin the mage. In other versions of the story, it’s Merlin who finds the abandoned baby and raises him to become a wizard with skills to match his own. Oh. Yes, many tales associated with the Mabinogion go on to form the Arthurian cycle and if we are to include those, then Merlin would have to be among my favourite characters of the Mabinogion. But, alas, I have filled my ration of five already, so… that’s another story.

Win a copy of all three parts of the epic fairytale fantasy series, This, by Remy Dean with Zel Cariad

We have copies of all three part of from Remy Dean’s epic fairytale fantasy series, This, for a lucky #FolkloreThursday newsletter subscriber this spring!

‘They say, “What you don’t know can’t hurt you,” right? Well, of course that’s not really true. They also say, “Knowledge is power.” Well that’s not always true either… because, somewhere between not knowing and knowing, there lies imagination. That’s the key… the key that unlocks secrets.

It did, once upon a time, and it still does today…

It began a long time ago, but for Rietta, it really began when she met Carla, another very special and extraordinary person, and realised that they shared the same dreams. Or perhaps it all started when Rietta and Carla found the severely injured dog in the woods, becoming firm friends as they tried to nurse it back to health and happiness. Then there was the ‘thing’ that they glimpsed watching them from the shadows, and the mystery of the missing standing-stone… but when they find the key to another realm, well, then things really start happening!

‘This That and the Other’ is imaginative fantasy, on an epic scale. The story follows the special friendship between two girls who embark on a magical adventure together, across the three realms. It is a modern fable inspired by Welsh fairy tales and folklore, in the tradition of ‘The Neverending Story’, ‘The Box of Delights’, ‘The Chronicles of Narnia’…’

Sign up for the #FolkloreThursday newsletter to enter (valid April & May 2020; UK & ROI only).

The book can be purchased here.

References & Further Reading

Menna Elfyn, Gillian Clark and Catherine Fisher, 2014, BBC Wales History Myths and legends: The Mabinogion

Sebastian Rider-Bezerra, 2011, The Camelot Project: A Brief History of the Mabinogion, University of Rochester

Sioned Davies, 2008, The Mabiniogion, Oxford World’s Classics

Lady Charlotte Guest, 1877, The Mabinogion, online via Sacred Texts

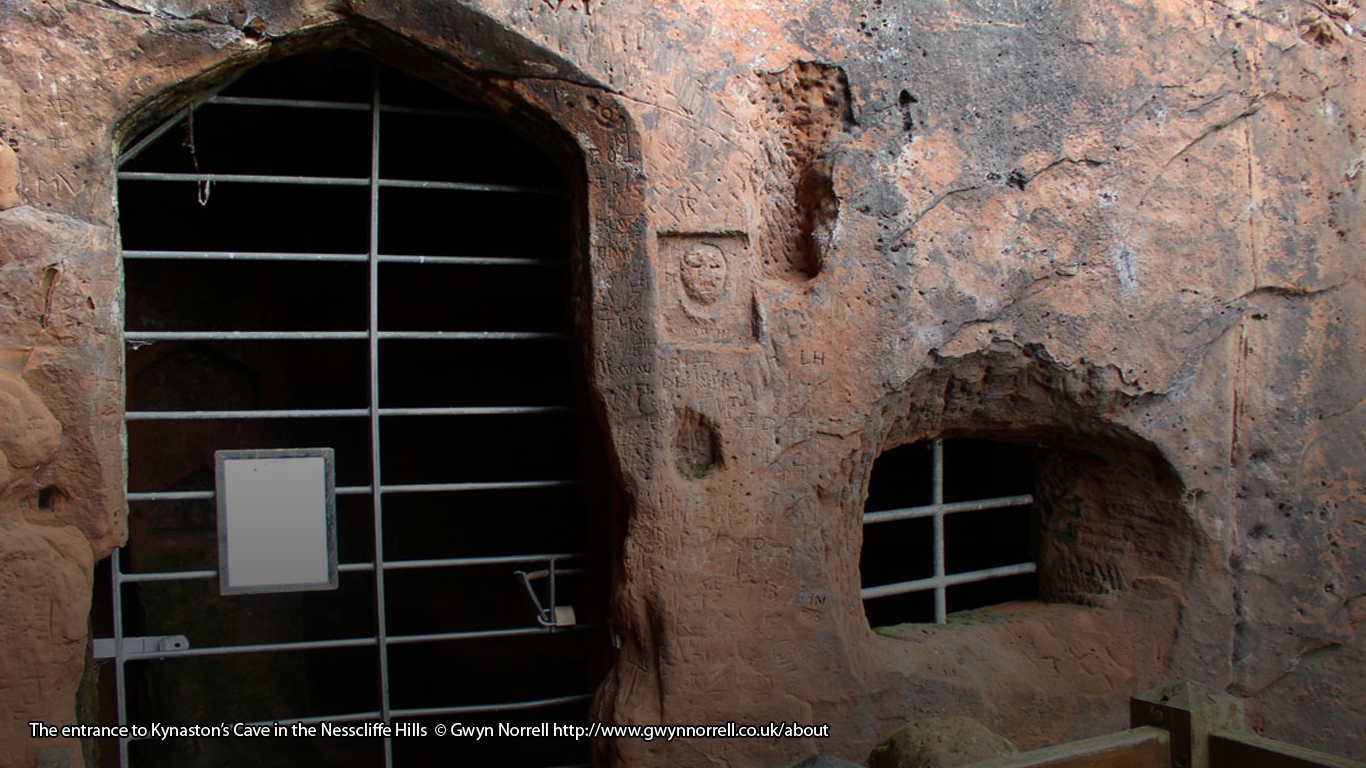

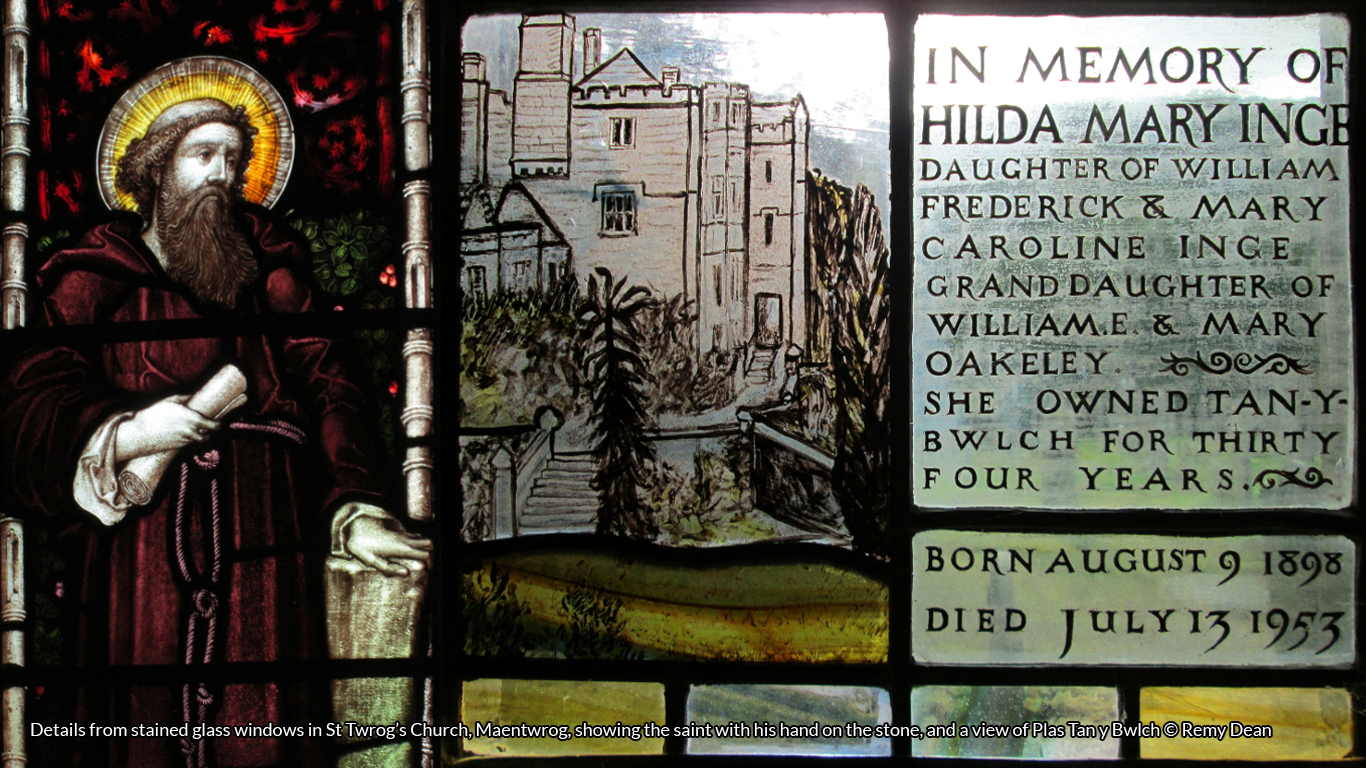

Twm Elias, Tales of the Mabinogion, Annual Lecture Series, Plas Tan y Bwlch