Skeletons are a common costume choice at Halloween; but they’re the ultimate symbol of death. Finding lost or buried bones is common in Gothic stories. There’s even a profession dedicated to understanding the secrets they conceal (forensic osteology). The skeleton bears witness to whatever cruel fate befell the individual. Even the Grim Reaper often chooses the guise of a skeleton, pointing a bony finger at his next victim. Folk tales and legends surrounding skeletons appear all over the world. In Lithuanian folklore, you can find the Žiburinis. This forest-dwelling spirit is a glow-in-the-dark skeleton. According to the legends, seeing one was bad luck; a sighting always meant someone was close to death nearby.

So come, take my outstretched collection of bones wrapped in skin, and let’s explore the folklore of skeletons…

NB: Bones do appear in folklore and legends through their use in divination, but as these are often chicken bones, they fall outside of our scope here. We’re looking at human skeletons…

As I Am, So You Shall Be

One of the key functions of the skeleton or skulls in art is as a memento mori. Their appearance derives from the Dutch vanitas paintings of the 16th and 17th centuries, where the bones came to represent the Latin phrase ‘remember you must die’. It’s cheerful stuff.

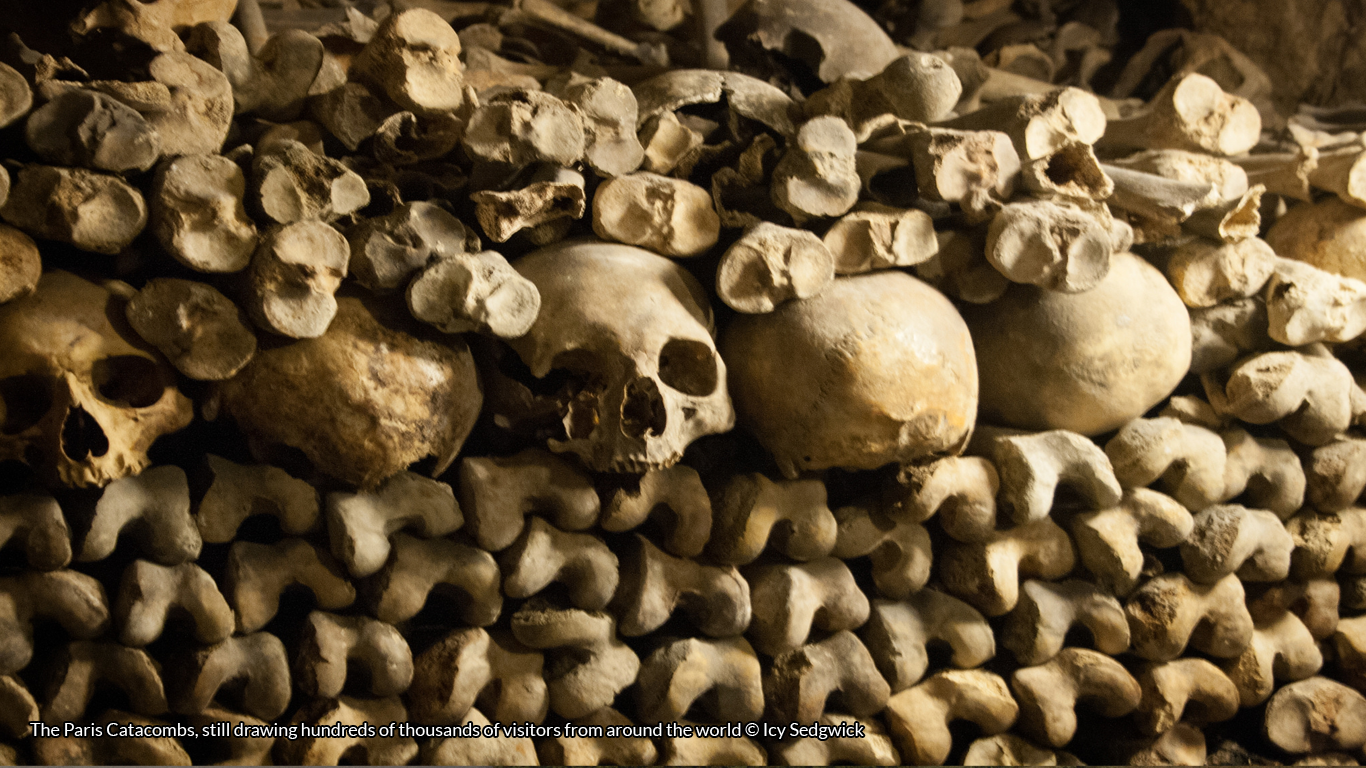

Skeletons become memento mori in unintentional ways. Overcrowding and outbreaks of disease prompted the Parisian authorities to close several city cemeteries in the 18th century. They relocated the bones to the abandoned lime quarries beneath the city, forming the infamous Catacombs . They opened to visitors in 1874, who still flock to see the enormity of the spectacle of twisting corridors of bones.

Artistic bone displays also appear at the Chapel of Skulls in Czermna, Poland, and the Sedlec Ossuary in the Czech Republic, among other examples. You often see the skull and crossbones on pre-20th century gravestones as a memento mori. Some believe it’s because the skull and femurs (the crossed bones) are the last part of a skeleton to decompose. The piles of bones in the Paris Catacombs would support that theory.

Skeletons are still creepy. Just look at the skeletons in Poltergeist (1982), erupting through the floor of the house and into the swimming pool. And yes, those were real skeletons. The production design team felt fake skeletons looked too uniform and sourced actual sets of bones.

But let’s look at skeletons in folklore, shall we?

The Eight-Foot Skeleton in Arizona

Some ghosts may take the form of skeletons, stalking the land in the hopes of finding their lost resting place. One such spirit appears in Superstition Mountains in Arizona. Described as being eight feet tall, this roaming skeleton carries a lantern; some tales say he carries the lantern before him, others say he bears a lantern light that shines through his ribs. The skeleton doesn’t seem to go out of its way to scare people. When a prospector shot at it, it continued on its random wander without breaking its stride. Many of the tellers of his tale think that the skeleton is a lost prospector, searching for the Lost Dutchman mine. As with all good quest narratives, the mine apparently contains untold wealth. If only someone can find it…

Skeletons and the Calavera

You can’t discuss skeletons at this time of year without acknowledging the sugar skulls of Mexico as part of the Día de los Muertos festivities. The practice of giving these skulls as gifts prompted artist Jose Guadalupe Posada to begin drawing calaveras, or bony skeleton figures, in the nineteenth century. Their popularity has led the skeletons to become synonymous with the Día de los Muertos.

Posada capitalised on their success, with satirical calaveras or figures that engaged in ordinary daily life. The name ‘calavera’ comes from the poetic broadside of the same name. These publications often satirised politicians or rich people. Some people even hired writers to compose a calavera for them, with a skeleton drawing accompanying the finished piece. The intention behind them links back to the memento mori – the idea that we’re all mortal and we’ll all meet our end some day.

The calavera connects with the cult of Saint Muerte, known as the ‘Bony Lady’. This popular folk figure attracts outright condemnation from the Church. But according to R. Andrew Chesnut (2012), Santa Muerte has become more popular than every other saint in Mexico, aside from St Jude. As a folk saint, she hasn’t been officially canonised by the Catholic Church. Instead, she’s a spirit of the dead, whose powers to effect miracles makes her holy. Santa Muerte rises above these spirits because, for her believers, she is Death. Yet unlike the Grim Reaper, she’s a positive figure, offering healing and helping her followers reach the afterlife.

Skeletons and Superstitions

In Worthing, Sussex, skeletons are linked with a Midsummer tale. According to the legend, first recorded in 1868, skeletons emerged from an oak tree near Broadwater Green on Midsummer’s Eve. They danced until dawn and then sank back into the ground when the sun’s rays warmed the soil. Perhaps the story isn’t so far-fetched. Daniel G. Brinton notes a belief that the word ‘bonfire’ comes from ‘bone-fire’ – in essence, a fire used to burn bones as a form of sacrifice. He noted that, in 1890, remote parishes in Munster and Connaught in Ireland still burnt a bone in their St John’s Eve bonfires. Are these bones symbols of the earlier Summer Solstice sacrifice?

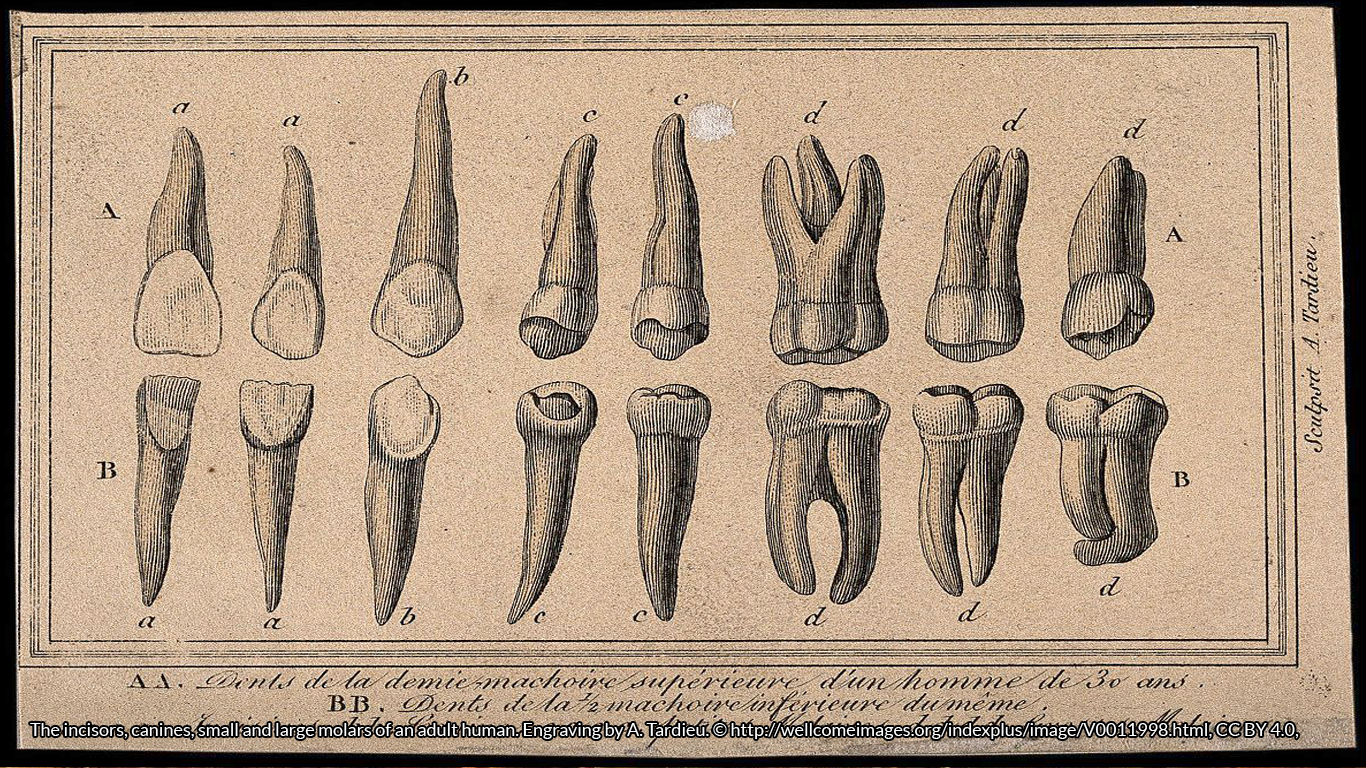

Brinton also notes the old belief that “the personality of the individual clung to his skeleton“. Perhaps it explains the superstition that if you remove a human bone from a cemetery and take it home, you’ll be tormented by the corpse’s spirit until you return the bone.

He does also relate an old belief that human bones held medical virtues. Apothecaries might add ground up bones to a range of concoctions. A popular 17th-century superstition claimed that ale was more intoxicating if you’d mixed the ashes of human bones into it. The custom was even officially forbidden in Ireland.

In Jersey, the Ankou (harvester of the dead) often appears as a skeleton. Sometimes he wears a shroud. He trudges around the countryside with a cart, collecting the dead. In some tales, skeleton servants accompany him and “he stands in his cart scything his harvest of the dead” (Bois 2010). You can hear either the cart wheels creaking or the dead screaming, announcing his approach. If you feel yourself pushed into a ditch, beware; this omen foretells impending death. Feeling a shudder means he will return soon.

We haven’t had the time or space to delve into the mysteries of religious relics (often bones), or the legends that cling to famous skeletons (see Richard III). But we have explored skeletons in art, in ossuaries, and superstitions that accompany the bony framework we all share.

Question is…what does the skeleton mean to you?

Recommended Books from #FolkloreThursday

References

Bois, G. J. C. (2010), Jersey Folklore & Superstitions Volume One, AuthorHouse.

Brinton, Daniel C. (1890) The Folk-Lore of the Bones

Cheshunt, R. Andrew (2012) Devoted to Death, Oxford University Press.

![Lupercalia by Andrea Camassei, c. 1635 [Public domain] https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Camasei-lupercales-prado.jpg#/media/File:Camasei-lupercales-prado.jpg](https://folklorethursday.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/valentinesday.png)