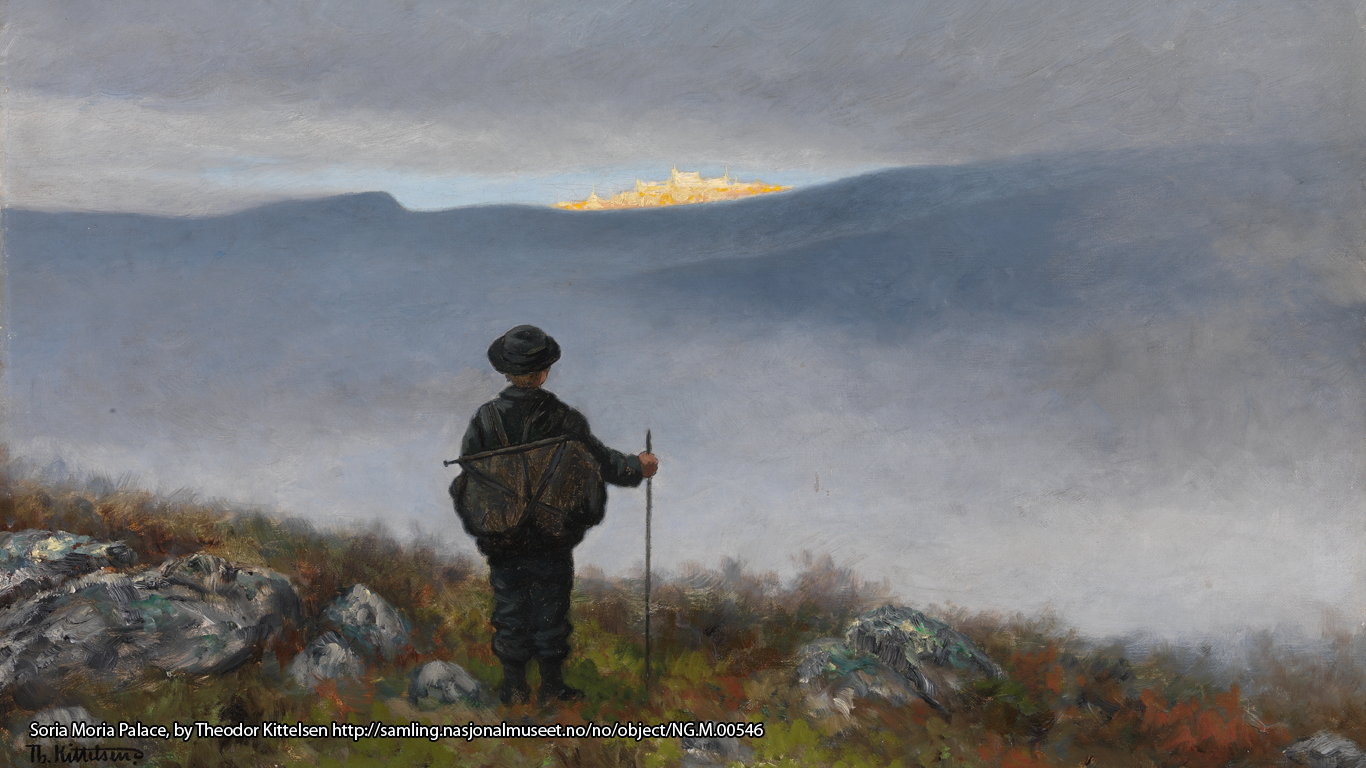

The Norwegian folktale, “East of the Sun and West of the Moon,” in which a white bear comes to take a poor girl away, is loved by people the world over. It is also part of a huge cycle of folklore and myth that has spanned Eurasia in the last 2500 years.

Of the few Norwegian folktales known in the English-speaking world, “East of the Sun and best of the Moon,” the tale of a white bear that promises a poor family wealth in exchange for their youngest daughter, is one of the best loved. Peter Christen Asbjørnsen and Jørgen Moe assembled the tale from various records they had made during their collection tours, and it was first published in Asbjørnsen and Moe’s second volume of Norwegian Folktales (1844).

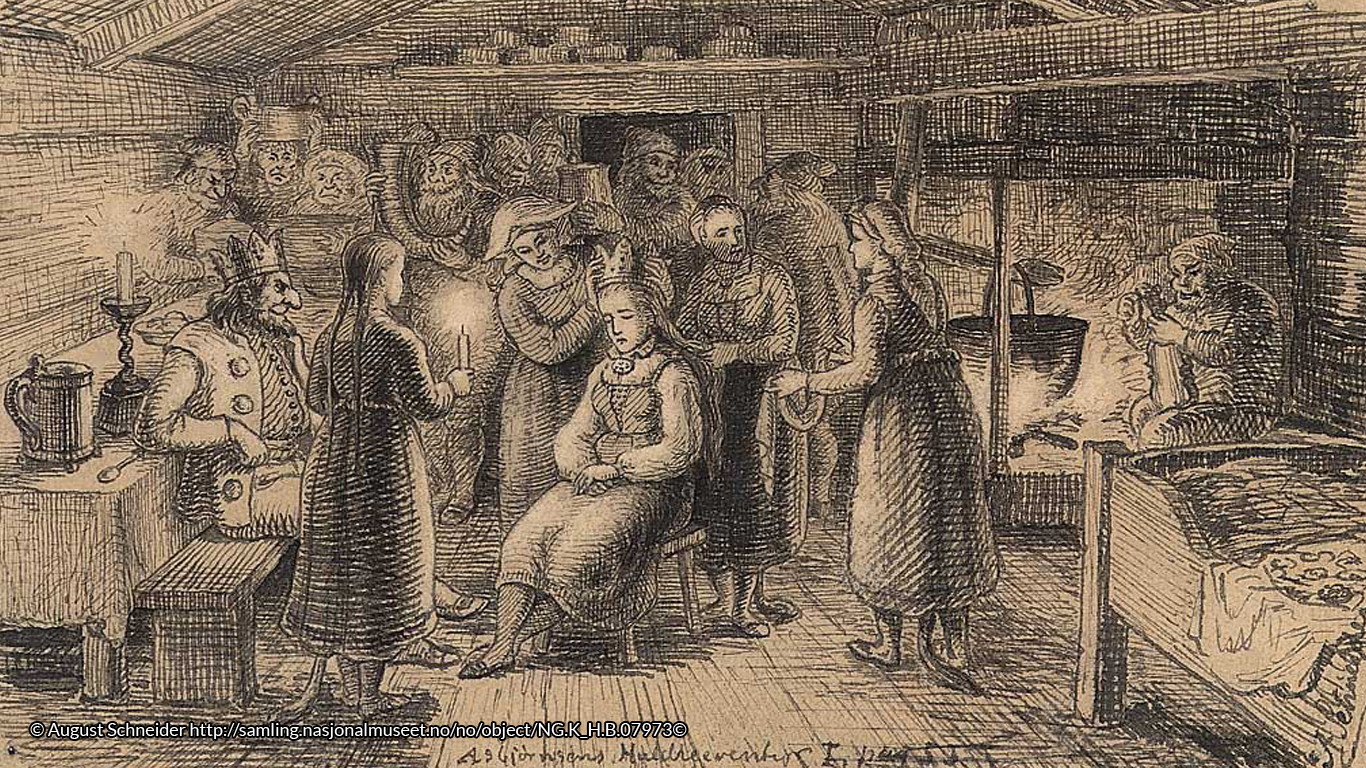

In all, around 80 different variants have been recorded in Norway, including “White Bear King Valemon,” which is just as much a favourite. Here the girl is a princess instead of a pauper, and the white bear entices her with a wreath that no goldsmith is able to replicate. This version also has the princess fall pregnant three times, her lover removing the baby on each occasion before he disappears. Of course, they are all reunited in the end, after the girl releases her sweetheart from the troll-hag who has bewitched him.

Folklorists using the scholarly Aarne–Thompson–Uther classification give folktales of this type the number ATU-425a, and the general title “The Search for the Lost Husband.” Together, these stories comprise a huge cycle of folk narratives, which encompasses tales from right across Eurasia. In the Romanian tale, “The Enchanted Pig,” collected by Petre Ispirescu, three princesses discover a prophecy concerning who each will marry; the youngest will marry a pig from the north. In the Spanish tale, “The Sprig of Rosemary,” collected by Dr. D. Francisco de S. Maspons y Labrós, the daughter marries a man who accuses her of stealing his firewood. In the Irish tale, “The Brown Bear of Norway,” collected by Patrick Kennedy, and the Scottish tale, “The Red Bull of Norroway,” published by Robert Chambers, the princesses name their own husbands in jest. In “The Black Bull of Norroway” also by Chambers, a bull comes to take the daughter away. The Grimms published a few of tales of the same type; the plainest of these is “The Iron Stove,” in which the the princess fears she has to marry an iron stove, not perceiving the prince who has been enchanted inside. Jan-Øyvind Swahn has reportedly treated as many as 1,137 different variants in his comprehensive work on this tale type,1 and has apparently found an early allusion to “The tail of the thre futtiit dog of norrovay,” a folktale of this kind, in The Complaynt of Scotland (1549).2

Ørnulf Hodne summarises the skeleton plot of ATU-425a as follows:

For certain reasons a girl is promised to a monster (white bear, wolf), a transformed prince who is a man at night. After a while she visits her home, but is warned against listening to her mother’s advice. She breaks the prohibitions (kisses him, shines a light on him) and loses him. She undergoes a sorrowful wandering to recover him, and receives the magic objects she needs and is helped to reach the ogre’s castle, where he is living with a witch. She succeeds in disenchanting him and regains him. The false bride is unveiled and dies.3

Although these tales are familiar as folklore, the result of oral traditions, they probably have their origin in literature. Indeed, the literary sources are much older than the oral traditions we know of. In “Pintosmauto” from Giambattista Basile’s Il Pentamerone (1634), the girl Betta, who is dissatisfied with every suitor who attempts to win her, makes herself a husband out of Palermo sugar, almonds, and precious stones. She names him Pintosmauto, after bringing him to life by praying to the goddess of love, in imitation of the Pygmalion myth. Karen Bamford finds earlier evidence of the tale in Shakespeare’s All’s Well that Ends Well (1623); it appears the Bard was familiar with the type, and Bamford speculates that he probably took the motif of the lost husband from Bocaccio’s Decameron (1353). As far as we are aware, though, the oldest of this kind of tale is the enormously productive story of “Cupid and Psyche,” embedded in Lucius Apuleius’s The Golden Ass (circa 180 CE), the only complete novel that has survived from the Roman Empire.

Reading “Cupid and Psyche” today is an interesting experience: this ancient text – the mother, as it were, of every last one of the tales mentioned above, and with which we have grown up – reads like a pastiche of its offspring. The major difference is the divine participation in “Cupid and Psyche,” which does not feature in the folklore. Otherwise, the motifs that we find in the folktales are all present: the beast whom Psyche expects to marry, her abduction, the hidden husband, her pregnancy, the persuasion to discover the identity of the beast, the light that reveals his beauty, the drop of hot oil or tallow, the separation, and the girl’s ultimately successful quest to regain her love, aided by supernatural helpers along the way.

Whilst Ruth Bottigheimer makes a connection to the earlier “The Girl Who Married a Snake” a tale from the Panchatantra (circa 300 BCE), she concludes that “‘Cupid and Psyche’ in its present form appears to be Apuleius’ own invention.”4 M. J. Edwards has found an antecedent to Apuleius’ story in the Sumerian tradition of Ereshkigal, the goddess of the underworld, who marries Nergal, who in turn is named in the Old Testament, which pushes the tradition a further 600–700 years into the past.5 Edwards warns against leaping “too rapidly from parallels to sources,” but it is reasonably safe to assume that stories that resemble the Cupid and Psyche myth were in oral circulation when Apuleius wrote his novel, all those years ago.6

When we consider the relationship between Apuleius and the myriad of folktales his work has spawned, all of the folktales named above, as well as many others, apparently have their origins in a single work of literary fiction by a named author. There has been a lot of movement back and forth between oral and written sources, before they were recorded in the early 19th century, but it appears that “East of the Sun and West of the Moon” may well contain traditions that date back to the cradles of civilisation.

Win a copy of Five Norwegian White Bear Tales by Simon Roy Hughes

This winter, we have a copy of Simon’s brilliant new collection of stories, Five Norwegian White Bear Tales, for one lucky newsletter subscriber, with one also going to one of our Patreon supporters!*

About 80 variants of the tale that is most familiar to us as “East of the Sun and West of the Moon” have been collected in Norway. It is arguably the best-loved of the Norwegian folk narratives that are recognised around the world, helped no doubt by the charming motif of the white bear that comes to take away the girl. There is a lot of scope for innovation within the general schema of the tale type. How the bear and the girl meet, how the girl is tested, how she loses and then recovers her husband may vary, but these five texts all very obviously tell the same story.

*Sign up for the #FolkloreThursday newsletter to enter our competitions (valid January and February 2020; UK & ROI only). For an extra chance to receive copies of the latest books and folklore goodies, become a #FolkloreThursday Patron supporter!

Recommended Books from #FolkloreThursday

Notes

1. Cited in Bettridge and Utley, 159. This rather exact number includes all ATU-425 tales, such as “Beauty and the Beast” (ATU-425c), which are probably from the same source, but which differ from the ATU-425a tales under discussion here.↩

2. Cited in Bamford, 69n. ↩

3. Hodne, 97. ↩

4. Bottigheimer, 5. ↩

5. See 2 Kings 17:30. ↩

6. Edwards, 93. ↩

References and Further Reading

- Karen Bamford. “Foreign Affairs: The Search for the Lost Husband in Shakespeare’s ‘All’s Well that Ends Well’” in Early Theatre, Vol. 8, No. 2 (December 2005): 57–72.

- William Edwin Bettridge and Francis Lee Utley. “New Light on the Origin of the Griselda Story” in Texas Studies in Literature and Language, Vol. 13, No. 2 (Summer 1971): 153–208.

- Ruth B. Bottigheimer. “Cupid and Psyche vs. Beauty and the Beast: The Milesian and the Modern” in Merveilles & contes, Vol. 3, No. 1, Special Issue on “Beauty and the Beast” (May 1989): 4–14.

- Edwards, M. J. “The Tale of Cupid and Psyche” in Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik, Bd. 94 (1992), p. 77–94.

- Ørnulf Hodne. The Types of the Norwegian Folktale. Oslo: Universitetsforlag, 1984.

- Jan-Øyvind Swahn. The Tale of Cupid and Psyche (Aarne-Thompson 425 & 428). Lund: CWK Gleerup, 1955.