The Roman goddess of the dawn (analogous to the Greek goddess Eos, the Germanic Ēostre, the Irish Brigid, etc.), Aurora is the sister of Sol and Luna, and early each day she races across the sky, dressed in saffron, heralding the arrival of her brother, the sun. Even though she is the sunrise, her name has been taken to denote the lights that appear in certain conditions in the northern hemisphere (the Aurora Borealis) and in the southern hemisphere (the Aurora Australis). The Auroras, as we know today, are dependent on the interactions of the sun and our upper atmosphere, and have thus appeared since before history began to be recorded. And it appears that each age of history has had their own ideas about what caused the Auroras, what they consisted of, and what they signified.

In ancient Greece, Aristotle wanted to “explain the cause of the appearance in the sky of burning flames and of shooting-stars, and of ‘torches’, and ‘goats’, as some people call them.” We don’t know the identity of the people who called the Aurora Borealis “goats,” nor why they did so, but Aristotle does explain the lights. There are four basic elements, which combine in various ways to give us every kind of matter that exists: “The earth is surrounded by water, just as that is by the sphere of air, and that again by the sphere called that of fire.” Aristotle’s “goats” are merely a local occurrence of some manner of turbulence that mixes air and fire, which of course causes a fire.

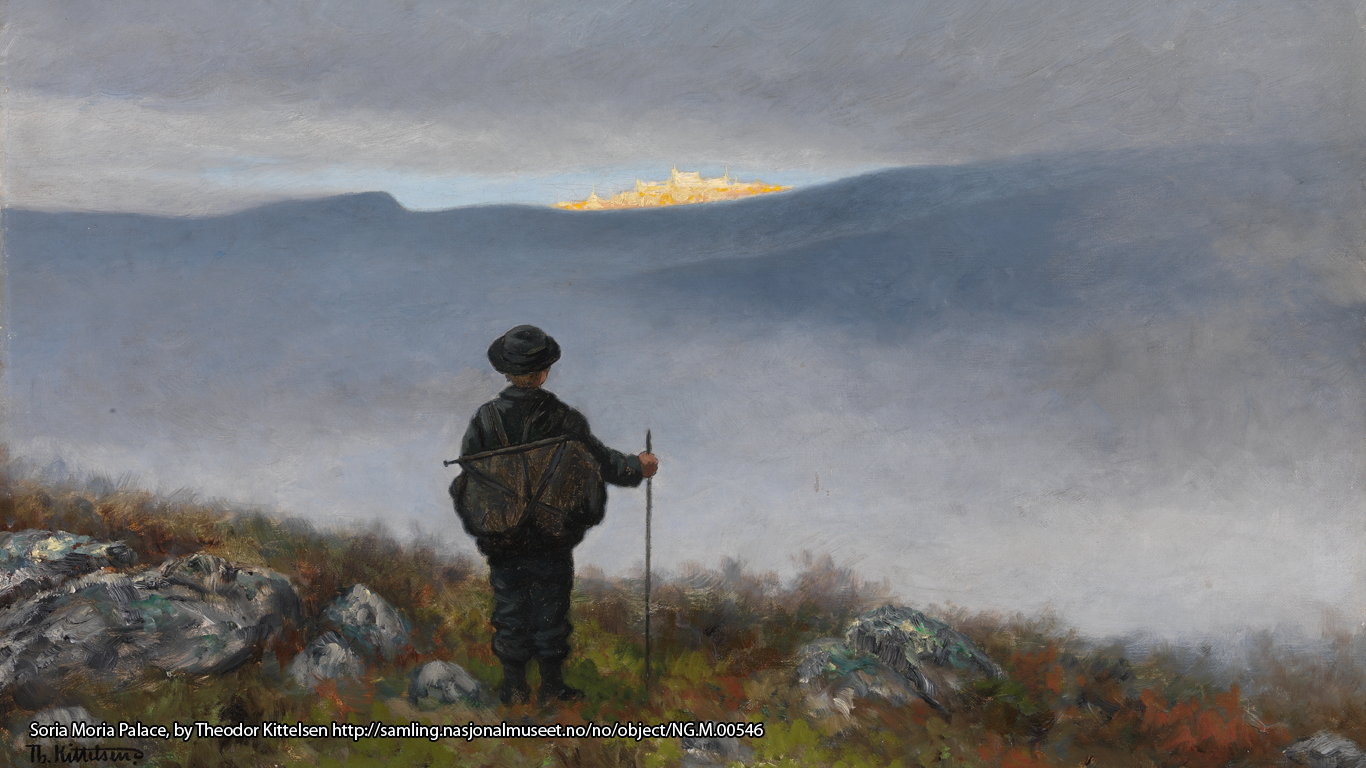

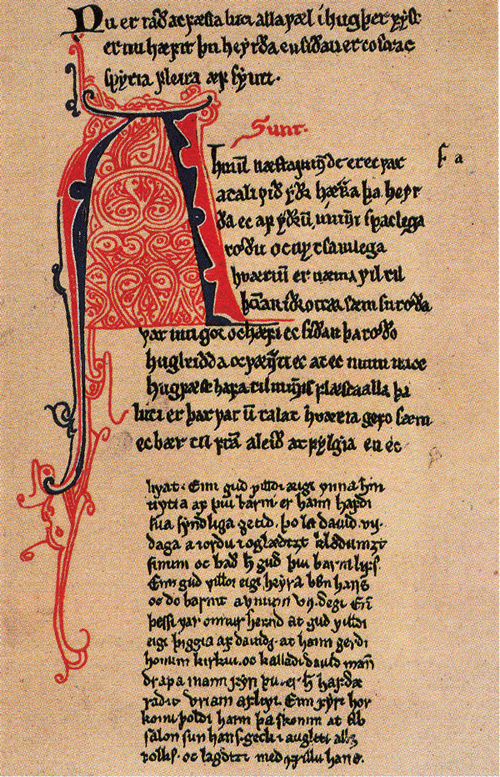

Professor of physics, Asgeir Brekke suspects that Snorri Sturluson’s description of the “bridge from earth to heaven” in the Edda may better fit the northern lights than it does the rainbow that Snorri suggests; Snorri, was simply attempting to interpret traditional material, after all. Brekke’s evidence comes from the Edda itself. First, Snorri’s description that Bifrost “has three colors” better fits the green, red and violet of the Aurora than the full spectrum of the rainbow. (Edda, 13.) Second, perhaps there is an oblique reference to Aristotle: “Then asked Ganglere: Does fire burn over Bifrost? Har answered: The red which you see in the rainbow is burning fire.” Rainbows don’t look like fire, but the Aurora does; a motif of fire recurs in the folklore of the northern lights.

The first naming of the northern lights as such appears in the mediaeval Konungs skuggsjá (The King’s Mirror), which is a didactic book in the mirrors of princes genre, written for the edification and upbringing of the sons of the Norwegian king Håkon Håkonsson (reign 1217–1263). The anonymous text is presented as a series of questions from a son, and answers from his father, and the subjects it covers range from the manners of kings and courtiers, to the natural wonders of the realm.

The son asks his father about “that thing […] which the Greenlanders call the northern lights” after discussing the wonders of the rest of the king’s dominion: Norway, Ireland, and Iceland. His father is quite honest; after discussing the geography of Greenland, and repeating the accepted propaganda concerning its pleasant climate (Erik the Red gave the country its name, hoping to attract settlers), he admits that he is uncertain about the nature of the Norðurljós. He describes the phenomenon: it is all the brighter when the night is darker, it never appears during the day, and seldom in moonlight. It looks like a distant flame, he says, and when it is at its brightest, it is possible to navigate and hunt by its light. There are three plausible explanations, the father says:

1. “these lights shine forth from the fires that encircle the outer ocean”

2. “during the hours of night, when the sun’s course is beneath the earth, an occasional gleam of its light may shoot up into the sky”

3. “the frost and the glaciers have become so powerful there that they are able to radiate forth these flames”

Of the three explanations, he judges the last to be most probably the truth, but offers little evidence to support any of the three hypotheses.

Speculation concerning the nature and significance of the northern lights has continued into the folklore of more modern times, too. In their article “Det historiske nordlys” (The Historical Northern Lights), Brekke and Egeland give a list of Nordic traditions. In Sweden, the Aurora may have indicated a civil war fought by angels flinging flaming fragments of fatwood at one another. Or perhaps the lights come from Sámi reindeer herders searching for their herds by torchlight. In Sweden and Denmark, the northern lights were thought to come from a fire-spitting mountain, given by God to bring warmth and light to the cold darkness of winter. Often folk feared a vengeful Aurora, which would maim or kill those who mocked it. And there was a widespread notion that old maids would in death be taken up to the northern lights, perhaps even providing fuel for its fires. The Sámi were afraid that the Aurora would come down to take or kill their children. On the Faroe Islands, children were warned to keep a hat on in the winter for fear the northern lights would scorch their hair off. This fear was possibly the reason Swedes would not cut their hair beneath the light of the Aurora. The earthy Norwegians, however, understood the northern lights to be “sildeblixt,” the gleam from huge shoals of herring, projected on to the clouds.

The northern lights have drawn the fascination of humans since we began keeping written records. Many of the earliest records tell of oral sources, which means the fascination goes even further back in time. And no matter whether the Aurora is best represented by goats or flames or the gleam of fish, our fascination remains; few can but wonder at the show, when the glimmering lights appear in the sky, on a clear night.

Recommended Books from #FolkloreThursday

Referencecs & Further Reading

- The King’s Mirror.

- Meteorology.

- Asgeir Brekke. Ottar: Nordlyset: Fra fantasi til forskning, No. 252. Tromsø: Tromsø museum, 2004.

- Asgeir Brekke & Alv Egeland. “Det historiske nordlys.” Ottar, No. 121-122. Tromsø: Tromsø museum, 1980: p. 8-21.

- Snorri Sturluson. Edda.