The loss of your first tooth is a pretty important event in your life. Providing you carefully place the tooth under your pillow and leave it for the Tooth Fairy, it can also be your first experience of earning money. But who is the Tooth Fairy, and where did she come from?

Enter the Tooth Fairy

Compared with Santa and the Easter Bunny, the Tooth Fairy appears to be a relatively recent addition to the childhood canon. Oral references to her emerge at the turn of the 20th century. But she doesn’t make her first appearance in print until 1927, in The Tooth Fairy: Three-act Playlet for Children by Esther Watkins Arnold.

The contemporary Tooth Fairy custom sees children leave their baby teeth under their pillow for collection, in exchange for money. Some children place notes alongside their tooth, asking for a new one. In some places, children believe the Tooth Fairy will only come if they’ve been good. She won’t come at all if they try to stay awake to see her.

Rosemary Wells (1991) notes that the Tooth Fairy in her recognisable form is largely missing from European folklore. Wells even called her “America’s only fairy”. But while references to the Tooth Fairy are largely absent until the early 1950s in Britain, Tad Tuleja (1991) points to the Venetian witch, Marantega, as an early European version. Marantega also appears in local folklore as a St Nicholas type figure. But she’s more known for exchanging teeth placed under pillows for coins.

In late 19th century France, accounts exist of children leaving their teeth under their pillow, and the Virgin Mary no less makes the exchange for money or toys. Tuleja argues that the exchange of teeth for money is the first step towards educating children about the value and power of money. It must be working. According to Chris Taylor, the Visa credit card company even ran a survey in 2013, and found that the national average had risen 23% to $3.70 per tooth!

But she’s not just buying teeth

Wells disagrees about the link between the Tooth Fairy and a child’s education about capitalism. Children go through a range of transitional phases before they become adults. Losing the baby teeth is usually the first of these. And given it’s sometimes accompanied by pain and bleeding, it can be scary. Even when it’s not, it’s incredibly disconcerting to start shedding teeth!

Who better to make the process seem less traumatic – and even profitable – than the Tooth Fairy?

Cindy Dell Clark (1998) calls the Tooth Fairy a mediating figure, helping the child to process the loss of their tooth. The Tooth Fairy allows the tooth to “be purposefully put to rest”. This role makes the Tooth Fairy a slightly Gothic figure, and she plays an almost funereal role in the disposal of the lost tooth.

It’s hardly surprising; the loss of the baby teeth marks the ‘death’ of childhood and the onset of puberty. The Tooth Fairy stands guard at the boundary between these developmental stages.

But why does she want the teeth in the first place? According to the website toothfairy.org, the Tooth Fairy thought losing baby teeth was actually very exciting. Losing your first tooth is a sign that you’re on the path to being a grown up. She wanted to hold a lost tooth and experience some of that excitement.

So what did children do before the Tooth Fairy?

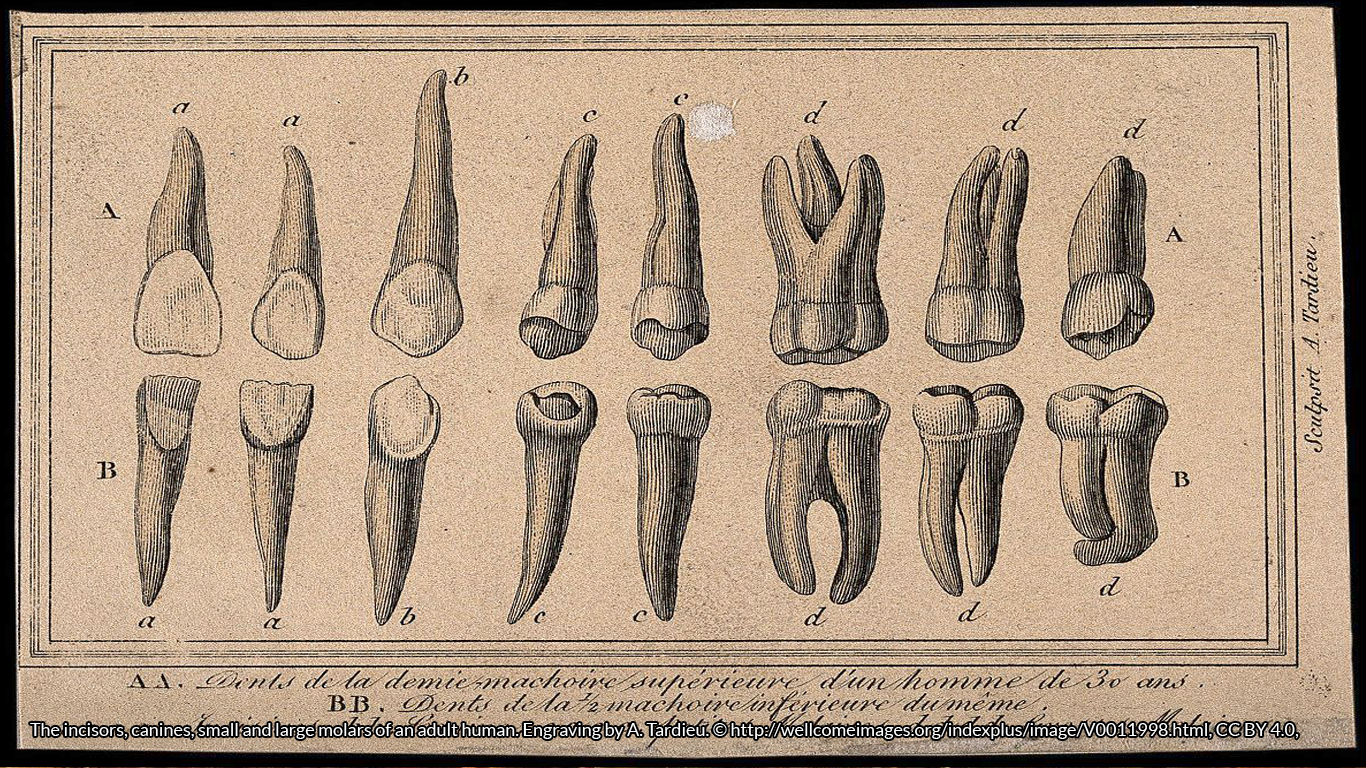

Dentistry as we know it is a relatively new form of medicine. But despite the primitive and often barbaric treatments available for pre-20th century adults, children still lost their baby teeth as they do now. So what did people do with them?

Discarded teeth were often disposed of by casting them into flames. Byrd Granger (1961) explains that teeth were often thrown into a fire and in 1870, Swedish children did so as a form of offering. Theodore Ziolkowski (1976) explains that there was a folkloric belief that teeth should be “salted and burned” so that witches could not use them in their rituals.

Wells even points out that all cultures have lore surrounding the disposal of baby teeth. The methods of disposal all seem to boil down to nine essential characteristics. A tooth could be thrown at the sun or into the fire; it could be thrown between the legs or onto a roof; offered to an animal by leaving it in a mouse hole; burying it; hidden; pushed into a tree; or swallowed.

Leaving the tooth for mice and rats is a particularly common ritual. Anthropologists believe this particular sacrifice was intended to help the child’s adult teeth become strong and sturdy – just like the rodents themselves.

Leo Kanner (1928) describes a Balkan ritual that involved the burying of the first lost tooth within a tree. If it was specifically conducted by an old woman, and the covering was blocked with a peg, then the child would never suffer from toothache.

What about adult teeth?

The Tooth Fairy has never taken care of lost adult teeth. That task falls to the adult in question. Granger makes the point that adults needed to have their full set of teeth on Judgment Day. They didn’t need to have them in their jaw, but they did need to have them handy. If you hadn’t stored all of your lost adult teeth in life, you’d have to look for them after death.

Yet there was a loophole. In Sheffield in around 1895, you could dispose of your shed adult teeth by throwing them into the fire. As long as you said “Good tooth, bad tooth, Pray God send me a good tooth” you didn’t need to worry about looking for them on Judgment Day.

Commentators have noted the growth in popularity of the Tooth Fairy coincided with the success of Disney and his cinematic fairies. Far removed from the vicious or mischievous fairies of folklore, the Tooth Fairy leaves more than she takes. But whatever the reason that they like her, children take comfort in losing their teeth because of the promise of impending adulthood – and the accompanying monetary reward!

National Tooth Fairy Day is usually celebrated on February 28th or August 22, but don’t forget False Teeth Day on the 9th of March too!

Recommended Books from #FolkloreThursday

References and Further Reading

Dell Clark, Cindy (1998) Flights of Fancy, Leaps of Faith: Children’s Myths in Contemporary America, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Granger, Byrd H (1961) ‘Of the Teeth’, Journal of American Folklore, 74, 47-56.

Tuleja, Tad. (1991) ‘The Tooth Fairy: Perspectives on Money and Magic’ in The Good People: New Fairylore Essays, New York: Garland.

Wells, Rosemary (1991) ‘The Making of an Icon: The Tooth Fairy in North American Folklore and Popular Culture’, in The Good People: New Fairylore Essays, New York: Garland.

Ziolkowski, Theodore (1976) ‘The Telltale Teeth: Psychodontia to Sociodontia’, PMLA , 91:1, 9-22.

![Lupercalia by Andrea Camassei, c. 1635 [Public domain] https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Camasei-lupercales-prado.jpg#/media/File:Camasei-lupercales-prado.jpg](https://folklorethursday.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/valentinesday.png)