The tales surrounding this rather unassuming standing-stone are taller than the stone itself. Plas Tan y Bwlch is a grand manor house nestled amongst woodland on the slopes of the Moelwyn mountains in Snowdonia. It looks out across the Afon Dwyryd river to the village of Maentwrog …

Place names in the Welsh language are often descriptive or commemorative. Plas Tan y Bwlch, means the ‘place below the pass’ (or ‘gap’) and Maentwrog (mine-two-rog) means ‘the stone of Twrog’. ‘Maen’ is also the stem of the word ‘menhir’ used to describe a monolith that is longer-or-taller than it is broad. Twrog was a sixth-century saint who came from Brittany with his four brothers to found some of the earliest Celtic-Christian churches making North West Wales the first foothold of Christianity in Britain. Afon Dwyryd means ‘river of two fords’. Are you taking notes?

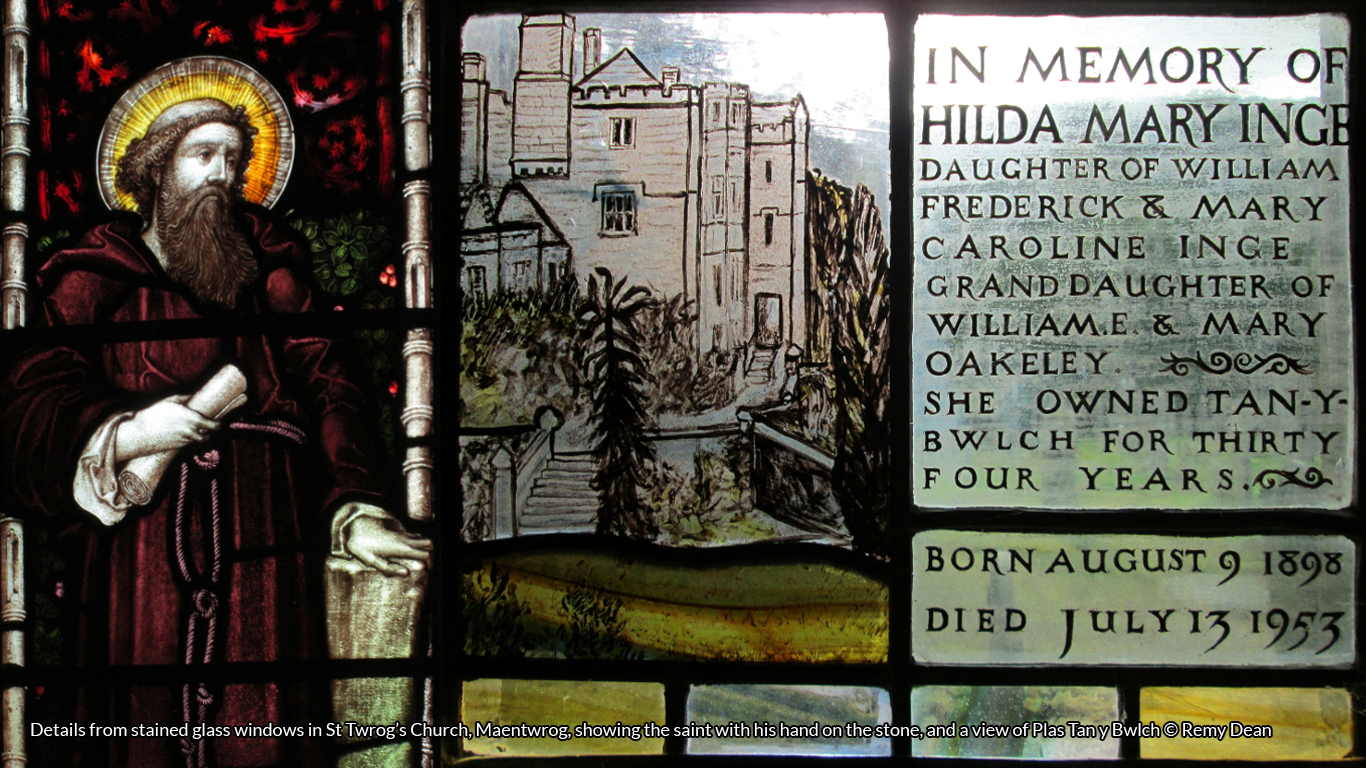

Nowadays, Twrog’s stone stands just inches outside the back wall of a church which was extensively renovated in 1896 by William Oakeley of Plas Tan y Bwlch. His wife, Mary, was an accomplished wood carver and made most of the interior wooden features we see there today. The church is surrounded by a grove of yew trees, the most ancient being 1300 years old. They are thought to have been planted as a source of wood for making longbows, though perhaps also a continuation of the pagan tradition of surrounding significant meeting places with yews. The stone itself is not just any old stone. It had been a central geographical and cultural feature long before Saint Twrog built the first church on the site …

The association between the stone and Saint Twrog stems from a fanciful local folktale:

When Twrog arrived in this place, its people worshipped a devil. Some say the devil, some say a she-devil. Twrog, being a missionary, was determined to dispel this pagan deity and establish a Christian community. He engaged the devil in a battle of body and soul to determine which was the strongest, but when neither had managed to best the other, after wrestling for half a day, they called a respite.

The she-devil sat down to recuperate while Twrog went up into the Moelwyn mountains to pray. In answer to his prayers, a shining angel appeared before Twrog and showed him to a clearing where the earth bore ‘special fruits’. Twrog ate the indicated mushrooms and was suddenly possessed of superhuman strength. From his vantage point, he could see his opponent sitting unawares, so he picked up a boulder and hurled it at her from across the valley. The huge stone sailed through the air and landed between her legs, half burying itself in the ground.

The she-devil was, of course, rather disgruntled by this turn of events. She knew that Twrog had cheated. Surely, he must have asked for divine help to win the contest. So, she reverted to her true form. Horns sprouted from her head and wings sprang from her shoulders, and she flew from the valley, never to return. Twrog founded his church on the site of his miraculous victory.

In other perhaps even older stories, un-picked from the rich tapestry of tales recorded as the Mabinogion, it is written that the stone marks the grave of King Pryderi, an important and recurring character in the Mabinogion, and the only character to feature in all four branches. The story of his final demise is indeed a colourful one, in more ways than one …

The Mabinogion is a very complex set of interdependent myths and legends and this ‘vignette’ has been simplified.

We begin with a visit to the court of Math, God-King of Gwynedd, by two of his nephews, Gwydion and Gilfaethwy. Math was a formidable war-god, and when he was not doing battle could only remain in the realm of mortals if his feet were cradled in the laps of young maidens. At the time of this visit, the virgin on foot duty was Goewin and upon seeing her, Gilfaethwy became sick with lustful desire and grew weaker and paler each day thereafter.

Gwydion hatched a plan to lure Math off to war so Gilfaethwy could have his way with Goewin, in the king’s absence. The plan was to steal some pigs owned by Pryderi, a neighbouring king of Dyfed. These were no ordinary pigs. Their flesh was the most delicious meat one could taste – far sweeter than oxen, deer or boar, and had been a gift from Arawn of Annwn, the Faerie-King of the Underworld.

Gwydion and Gilfaethwy went to visit Pryderi in disguise, among a group of bards and minstrels who entertained his court so well that Pryderi offered them a gift of their choosing. Gwydion requested the herd of pigs, but Pryderi explained that they had been gifted to him on condition that he would never give them away to anyone else. Gwydion already knew this, so he offered to buy the pigs instead. Pryderi explained that he had vowed never to sell them either. Gwydion already knew this too.

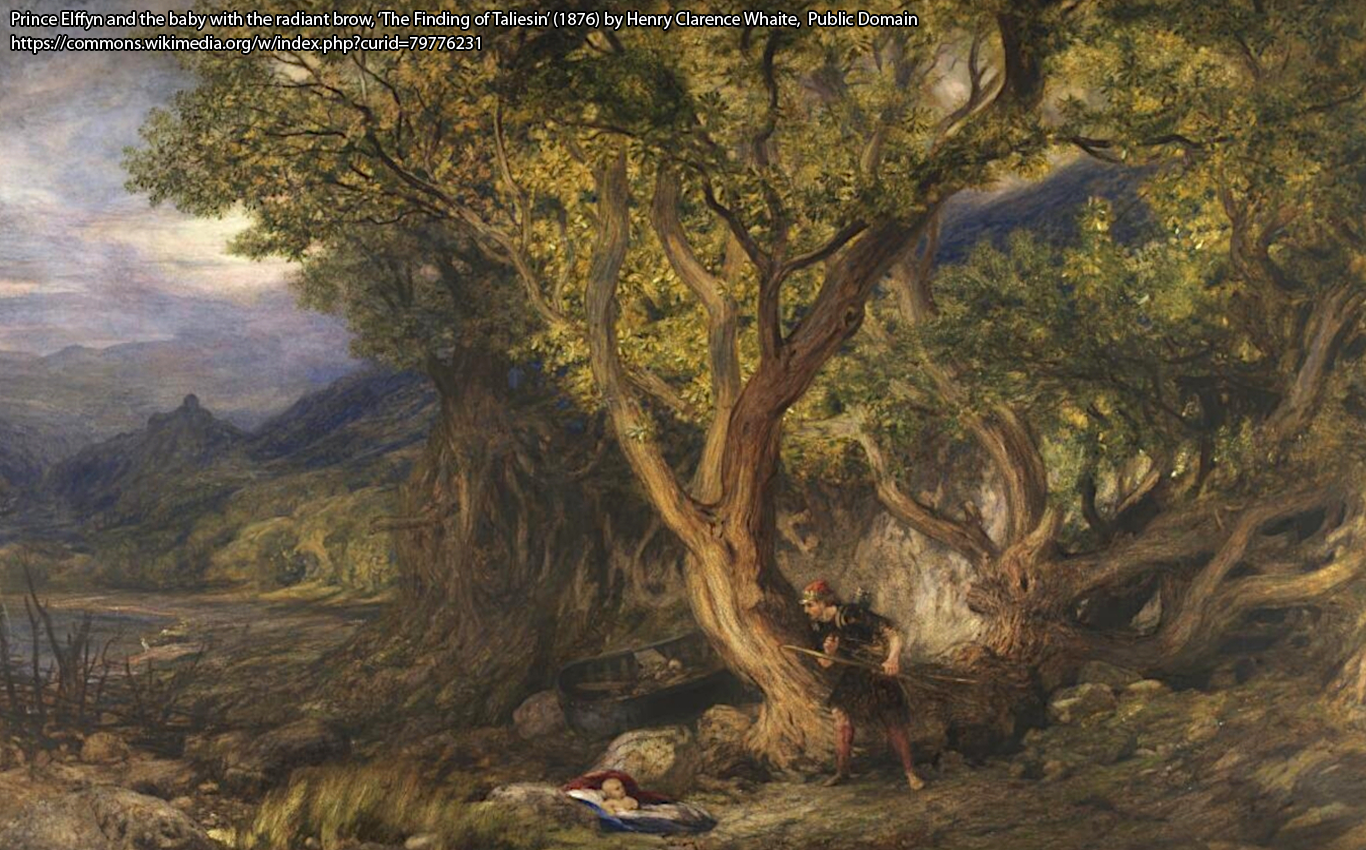

The next day, Gwydion went into the forests of the Moelwyns and collected twenty-four mushrooms. Using magic, he transformed the fungi into twelve noble steeds and twelve handsome hunting hounds. Not only were they all fine specimens, each steed was liveried with bridles and saddles of finest gold and each hound had a bejewelled, golden collar. He presented these amazing creatures to King Pryderi in exchange for the pigs, so he would not be giving, nor selling the swine. Pryderi agreed.

Gwydion and Gilfaethwy hurriedly left with the special ‘sweet-fleshed’ swine of Annwn and hid them in various places. (If you look at a map of the region today, you will find many place names with the pre-fix Moch – from mochyn, Welsh for ‘pig’.) Gwydion’s spell was a great glamour, but could only last for a day. So when Pryderi went to ready his fine new horses and hounds for a hunt, he found only mushrooms in their enclosures. He then realised who Gwydion must have been and took his army to the lands of Math to retrieve the pigs. The God-King Math heard that his kingdom was under attack and so was able to step off his maiden and ride into battle. Gilfaethwy pretended to join the march, but instead doubled back to find the fair Goewin alone, and with no king nor soldiers to protect her, forced himself upon her.

Even with magic on the side of Math’s army, the battle was fierce and many warriors were slain on both sides. Eventually, Pryderi suggested that the outcome of the war should be decided in single combat between himself and Gwydion, the one who had deceived and wronged him. Gwydion chose the place to do battle at Y Felenrhyd – the ‘Yellow Ford’ – a band of sand that ran across the Dwyryd estuary between high and low tides.

Where the land meets the sea, and where the sea meets the sky, are boundaries that span two realms and are potent magical spots. So, of course, with formidable magic on his side, the demi-god, Gwydion was able to defeat Pryderi, who was a brave though mortal man. The war was over and Pryderi was laid to rest at nearby Maentwrog, the stone erected to mark his grave.

The ‘true’ origin and meaning of the stone is also fascinating. Folklorists and archaeologists agree that the importance of fords was both symbolic and practical, and that the stone would have marked a safe crossing point through the marshlands. This would have enabled travellers to make their way down from the pass above Tan y Bwlch, cross the river Dwyryd and continue on through the opposite pass towards Dolgellau. The route became the roman road, Sarn Helen, and later a busy mediaeval drovers’ route.

In prehistoric times, the stone could have been a territorial marker, some say attended by a priestess who, for a small tribute, would bless travellers and ensure they had a safe journey across the valley. The stone is as old as the hills, literally, but was put in its place before the Roman period, before the arrival of Twrog, and long before the times of Dyfed and Gwynedd, and their mythical kings. Today, the stone marks a place where the realms of story and history may meet.

These stories were found during research into local folklore undertaken as part of my Writer’s Residency at Plas Tan y Bwlch, and a ‘thank you’ of legendary proportions goes to Twm Elias, who lectures there and hosts residential courses on the Mabinogion, and other fascinating topics, and has been a regular contributor to the magazine Llafar Gwlad, since its first publication in the 1980s . I am also most grateful to Andrew Oughton, for giving me the opportunity in the first place, and for access to the archives. Plas Tan y Bwlch is the Snowdonia National Park Environmental Studies Centre.

Recommended books from #FolkloreThursday

References

Merfyn Williams and Twm Elias, 2015, Plas Tan y Bwlch, Snowdonia National Park Centre, ISBN 978-1-84524-237-4

Evangeline Walton, 2012, The Mabinogion Tetralogy (collected), Duckworth Overlook.

Sioned Davies, 2007, The Mabinogion, Oxford University Press.

Lady Charlotte E Guest, 1877, The Mabinoion, Quaritch Books, (available in Dover Thrift Editions.)