Despite a great many people knowing that Norway is awash with folklore, many would be hard-pressed to name a Norwegian folk narrative beyond the folk tales “The Three Billy-goats Gruff” and perhaps “East of the Sun and West of the Moon.” Yet, from these tales alone, we can surmise that Norwegian folklore features trolls, the four winds personified, white bears, and evil stepmothers. There is so much more, though. In fact, there is so much stuffed into the pages of Asbjørnsen & Moe alone that I have had to constrain myself, by discussing only the most well-known preternatural creatures.

Askeladden

Askeladden is the the archetypal folk hero of many a tale. Jørgen Moe, in his introduction to the second edition of the folktales wrote of Askeladden as the embodiment of peculiar aspects of the Norwegian national character. He is apparently lazy and naïve, but during the course of his adventures, he proves himself to be imaginative and resourceful. He always kills the troll; he always wins the princess and half the kingdom, to boot.

Might he merely be lucky?[1] It is certainly luck that brings him into possession of the various items that he uses to save the day. In “The Princess No One Could Dumbfound” he uses a dead magpie, a hoop, a potshard, two ram’s horns, and a wedge to shut the princess up, for example; but it is his wit, not his luck that allows him to shoehorn these items into some semblance of a plan to win her.

In “Per, Pål, and Espen Askeladd,” his luck brings him into possession of some more exotic items that he uses to win the princess; his witless brothers walk past the items, and thus are doomed to fail in their attempts. There is more than luck at work, here.

(There are too many Askeladden tales to link to individually here, but you will find them behind the link.)

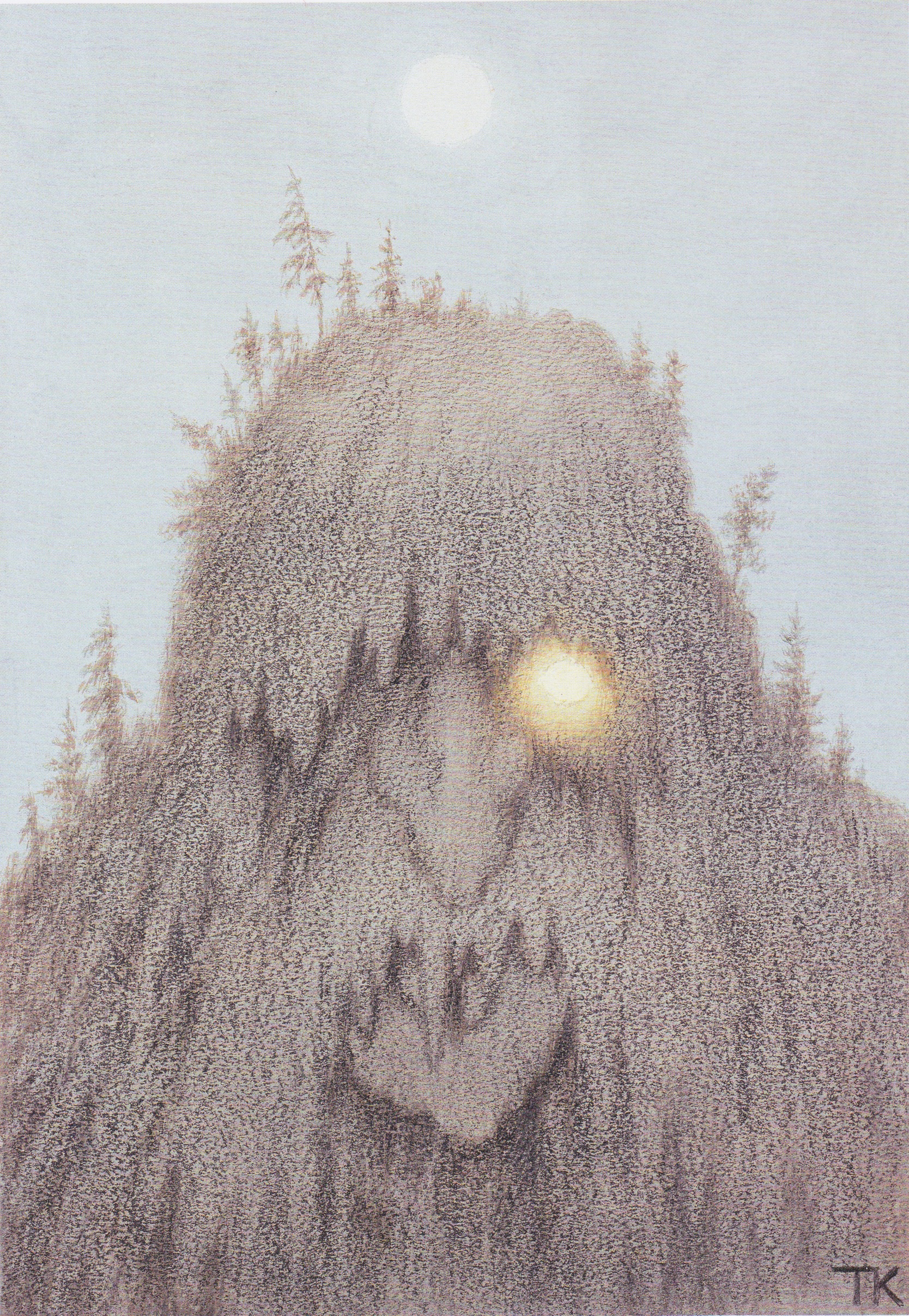

Trolls

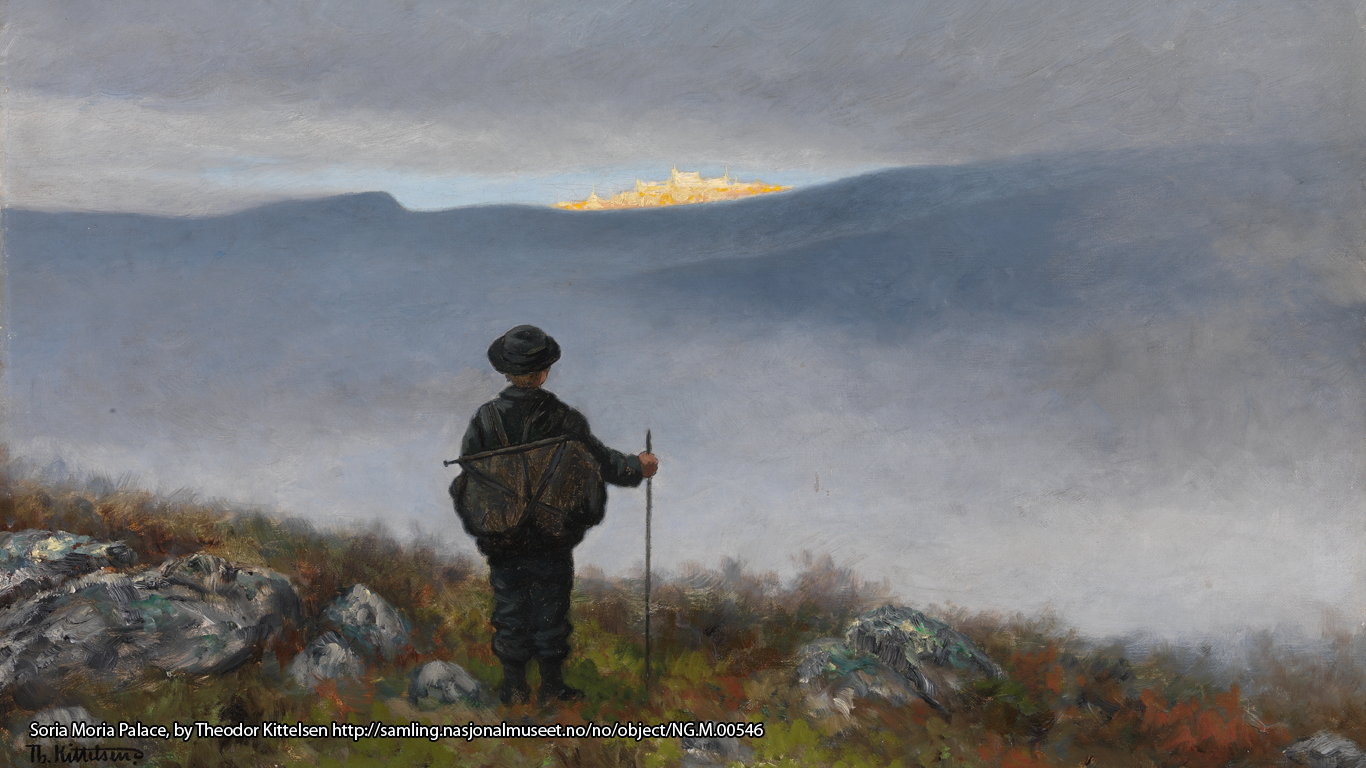

Askeladden deals with a number of trolls of varying size and form, but the element of luck is still present. In “Soria Moria Palace,” Halvor (Askeladden is a title, after all) deals with three trolls with three, six, and nine heads, dispatching them as quickly as he can with an unwieldy sword that he just happens to find in the palace, along with a tonic that gives him the strength to wield it. His seven-league boots and the help he receives from the wind is also fortunate rather than calculated; however, would anyone but Askeladden set out on the quest to win the princess in the first place?

Trolls are one of the most prolific preternatural creatures in Norwegian folk narratives; Askeladden is not alone in having to deal with them. “The Young Boys Who Met the Trolls in Hedal Forest” meet three trolls who have to share an eye and a wife, and are easily outwitted by the boys, who fool them into giving them gold and silver and “good steel bows” too. “Buttertub” defeats a troll family after he is fetched from his farm three times by a mound-hag who has her head beneath her arm. When the troll parents go to church(!), he kills the daughter, boils soup from her, and feeds her to them upon their return.

Cannibalism is a recurring theme. In “Askeladden Who Stole the Troll’s Silver Ducks” Askeladden fools the troll out of his seven silver ducks, his bedquilt with silver and golden squares in, and his golden harp, too. Then he tricks the troll’s daughter into giving him the knife with which he cuts her head off, and feeds her to the troll, who thinks he is eating Askeladden.

The troll in this tale ends up growing so angry that he bursts. Next to being put to the sword, bursting is the most common end of trolls; the “man of the mountain,” the troll in “The Hen Trips in the Mountain” ultimately bursts when the sun streams on him, after he in his wrath forgets the time of day.[2] Not all trolls suffer this fate, however; some can walk in the sunshine with impunity, such as the troll in “Askeladden Who Had an Eating Contest with a Troll.”

Giants

Trolls are not the only monsters in Norwegian folklore; huge giants also inhabit the pages of Norwegian folktales and legends. There are three Norwegian words that are translated as “giant”: kjempe, rise, and jutul/ jøtul. Kjempe simply means someone big or great, and these beings rarely, if ever, appear in Norwegian sources. Where the word is used, it is used metaphorically, or even as a threat. Rise [‘riːsə] comes from an Old Norse word that denotes a race of giant folk who are difficult to differentiate from the jötnar, a race descended from Ymir, the ur-giant from whose corpse Odin, Vili, and Vé fashion the earth, according to Snorri’s Edda. It is from the jötnar that the Norwegian word jutul has evolved.

The giant in “The Giant Who Had Not His Heart on Him,” a terrifying but ultimately stupid brute who kidnaps maidens, is a rise. He has the power to turn people to stone, and the ability to store his heart elsewhere, but he is susceptible to the charms of a maiden, which leads to his doom.

Although he is just as stupid as the rise, to the point of gutting himself, the giant in “The Jøtul’s Servant Boy” is a jutul. (In the more well-known variant of the tale, “Askeladden Who Had an Eating Contest with a Troll,” the boy eats against a troll). However, compared with the rises or trolls, jutuls can be quite benevolent, as may be gleaned from “The Jutul and Johannes Blessom,” in which the jutul gives Johannes Blessom a lift home for Christmas.

Hidden Folk

The gallery of Norwegian preternaturals also encompasses a number of hidden folk who are analogous to the fairies of other regional lores, chiefly the hulder-folk and the tusse-folk. The Norwegian word hulder comes from the Old Norse word huldú, which means “dark,” “hidden,” “covered,” “latent” Tusse comes from the Old Norse Þurs, which means “giant;” the word has evolved in Norwegian, though, now denoting something a folk that in many ways is similar to be the hulder-folk. Whether the hulder-folk and the tusse-folk are the same is a matter for other people to discuss. The tusse does not appear in Asbjørnsen & Moe except as a metaphor for someone or something very small or insignificant. The hulder-folk are a different matter altogether.

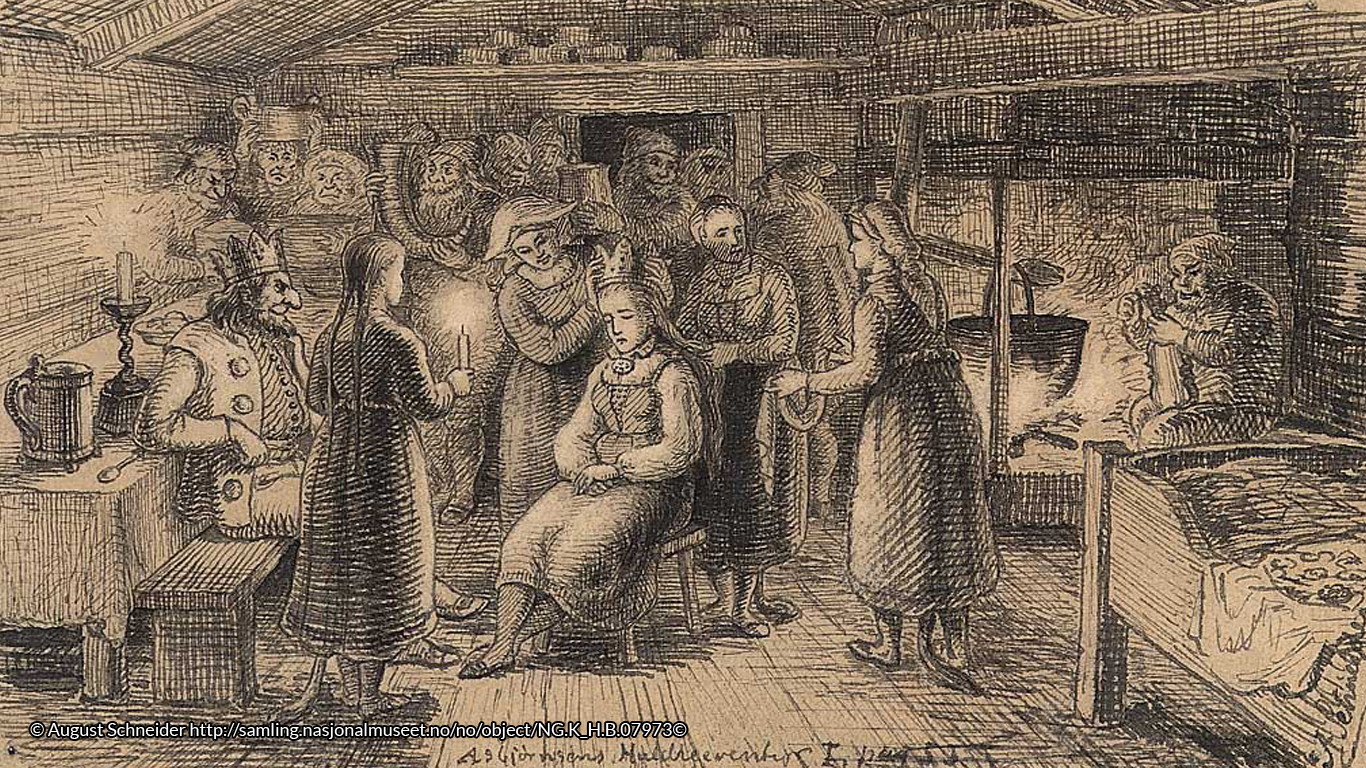

The hulder-folk live in the mound or the mountain, ie. anywhere underground. They apparently own great wealth, their halls being decorated in gleaming gold, and under certain circumstances, such as if one of theirs marries a Christian, they will generously share this wealth. Having said that, stealing, enchantments and snatching are rife, as I have written previously in “Meet the Hulders (Whether You Want to or Not).”

Although the hulder-folk appear primarily in the legends that Peter Christen Asbjørnsen published in 1845 and 1848, some folktales hint at their involvement. For example, when Askeladden throws some steel over the horses in “The Maiden on the Glass Mountain,” he is acting out a widespread folk-belief that the steal will break the enchantments of the hulder-folk. Likewise, the ball of yarn that “the old woman [who] came up through the tussock” gives Askeladden, and which guides him to his destination, in “The Golden Castle that Hung in the Air” alludes to the ball of yarn that the hulder girl uses to ensnare Mads in “Berthe Tuppenhaug’s Stories.”

This hulder girl has a tail, and it is by means of trapping her tail in a split log that Mads escapes. Hulder-folk may also lose their tails when they marry. Another hulder girl, in a legend recounted in “An Evening Hour in the District Governor’s Kitchen,” is obviously worried that people will see when this happens in the church, and so she arranges for a bridesmaid to stand behind her, to hide it from view. There is one very short folk tale-“The Box with Something Strange In“-that suggests that hulder tails were prized possessions.[3]

The Nisse

The nisse, or nis, is a small but powerful subterranean creature that is to be found in local legends, rather than the folktales. He typically wears a red woollen hat, as do a great many people in the folklore of the period (in fact red woollen hats were outlawed by the occupying German forces in the second world war as an unacceptable expression of Norwegian nationalism and therefore resistence), but we have a more detailed physical description in “An Evening Hour in the District Governor’s Kitchen.” He is said to be furry, at least on his hands, he has four fingers on each hand (no thumbs), and eyes that shine.

The word “nisse” comes from the given name Nils, which itself is derived from the Greek Nikolaos, suggesting a connection to the gift-giving saint of the same name. In fact, Santa Claus is called Julenissen (the Christmas nisse) in Norwegian.

Although he helps around the house, or the farm, he does not partake of the Christmas spirit. Some legends, such as those embedded in “An Evening at the Neighbouring Farm” (forthcoming), describe the immense strength of the nisse: “Gudbrand was so strong that he could lift a horse, and carry four barrels of rye, but the nisse was stronger; it was like wrestling a sauna wall, said Gudbrand, and however he wrestled, he was no good to move him from the spot.”

If he is pleased, the nisse will help on the farm. A legend in “On the Alexandrian Height” tells of a nisse, “a little fellow with a load of hay as large and as huge as a horse-load,” that can bring it dry into the barn, even though the rain is pouring down.

The theology student who remarks this questions the nisse concerning his purpose. He asks him first how long he has been at the farm. “For three lifetimes,” the nisse answers. Then the student asks him how many souls he has gained there on the farm. “I have got seven,” says the nisse, “and I’ll soon have two more.”

If the nisse is dissatisfied, then he can cause a lot of trouble before stealing the souls of his household. The first rule of keeping a nisse happy is good porridge. A girl in “An Old-fashioned Christmas Eve” offends him, by offering him oats and milk in a trough on Thursday evening, instead of sour-cream porridge. He takes his revenge by dancing a Halling with her all night, “and when some people came to the barn in the morning, she was more dead than alive.”

Making sure he is not disturbed too early in the morning is another way of keeping him happy. In another legend in the same text, he protests being woken too early by knocking all the plates together and throwing them on the floor. After this incident, the kitchen girls persuade him to move, and he is much happier at his new place with the coppersmith: “It was quieter there, for they went to bed at nine o’clock every evening.” The presence of the nisse brings wealth to the coppersmith, “for people said that the wife there put some porridge in the loft for him every Thursday evening.”

Witches

It is very rare for the Norwegian word heks (witch) to appear in the folklore; most often witches are called trollkjerringer (literally troll-hag), which although it is used as a word for “witch,” may also denote a magic woman or a female troll. The ambiguity comes from the word troll, the Norwegian word for the preternatural creature treated above, but also the word for magic or enchantment. I try to make the distinction as clear as I can in my translation, but sometimes the choice of the most apt English term becomes a guessing-, and then a second-guessing game.

Some troll hags are clearly witches, such as those in “The Gravedigger’s Tales,” who fly on broomsticks (and in or on many other household items), hold black sabbaths in churches, steal milk, have congress with the devil, and are burned when found out. The miller’s wife in “Legends from the Mill,” who fails to burn down the mill a third time, and who leads a band of black cats, is also quite clearly a witch. Also, the shape-shifting women who plan their husbands’ doom, by means of a bewitched storm, in “Mackerel-trolling” are witches rather than trolls.

Other troll-hags are more ambiguous. The antagonist in “White Bear King Valemon” and its relative “East of the Sun and West of the Moon” is, for now at least, a troll-hag. But perhaps her behaviour is more witch-like than trollish; she intends to marry the prince, and keeps him in a different form until she is ready to do so. I may revise the term when the tales are next edited.

There are numerous other creatures inhabiting the pages of Asbjørnsen & Moe, but they occupy fewer pages than the creatures mentioned above.

The Neck

The neck (nøkken) only appears in one legend, but it is feared in others. The narrator in “A Night in the Northern Mark,” jumps at a booming noise from across the water. “Is it the neck?” he asks. “In Jesus’ name, don’t speak that way!” says his interlocutor, Elias, explaining that the sound comes from a northern diver.

The legend that features the neck may be found at the end of the text “On the Alexandrian Height.” A rowing boat, on its way out of Oslo Fjord is surprised by someone rowing a half-boat. The half-boat follows him, rows circles around him, and effortlessly outpaces him. He stops a couple of times, to drink a dram or two, and to see if he cannot rid himself of his bothersome companion. The second time he takes a break, a man comes to him, and asks him to row him to a wedding on Håøya. It is the king of Ekeberg, who is on his way to marry the king of Håøykollen’s daughter.

When they get out on to the fjord, the fellow in his half-boat is waiting for them, and the king of Ekeberg is enraged, and promises the rower a whole bushel of money, if only he will land first.

But it is the half-boat that lands first, and the neck-for it is he-rushes up the bank as a grey horse with a gilded saddle, lures the bride on to his back, and disappears with her, much to the disappointment of the king of Ekeberg, who races after them on a horse.

The Unicorn

The unicorn is another creature that appears in only one text, “The Golden Castle that Hung in the Air.” Here, Askeladden and his ass are on their way to the silver castle to rescue the first princess when “a unicorn charged them, as if it would eat them alive.” Understandably, Askeladden is “mostly afraid,” but the ass has him offer the unicorn “two-score bull carcasses” if only “it would go before them and bore a hole in the mountain so that they could get through.” It obliges, heartily: “When it heard this, it bored a hole and cleared a way through the mountain, so quickly that they could hardly keep up.” This unicorn is about as far removed from the classical idea of a beautiful horned horse as we may get. It more resembles a rhinoceros.

Dragons

“The Golden Castle that Hung in the Air” is also one of three texts that speak of dragons. Three dragons guard the silver castle, mentioned above. They are huge, fearsome beasts, but like the unicorn, they are easily bribed with hundreds of bull carcasses: “then they grew quite placid and good-natured, and let the boy go between them, into the castle.” These dragons then go with Askeladden, and bring back the golden castle back to the silver castle on their backs.

The dragons in the other two tales are not so easy to deal with. In “The Boy Who Turned Himself into a Lion, a Falcon, and an Ant,” the nine-headed, fire-breathing dragon first appears as a messenger who receives a tribute of pigs from the king, on behalf of the mound-troll who has abducted his daughter. The eponymous boy kills the dragon, and then goes on an epic journey before he discovers, beneath “the ninth tongue in the ninth head of the dragon,” the grain of sand that releases the princesses from the thrall of the trolls.

The last dragon is a proper nitpicker. In “The World’s Pay Is no Different,” a man discovers a dragon stuck in a hole. The dragon, having not eaten for a hundred years, would eat him. The man begins to negotiate: “I saved your life,” he says, “and so you will eat me up for my trouble; that is shamefully ungrateful.” They seek an arbitrator among the animals who happen past. A dog that has been abandoned in its old age, and a horse no longer worth its feed, both side with the dragon: the man may expect nothing more from the dragon-“the world’s pay is no different,” they say.

Finally a fox is appointed arbitrator. He sides with the man, for the price of his chickens, and advises him to fool the dragon back into the hole, whereupon he drops the stone slab back into place, trapping the dragon again.

I could continue at length (as if I haven’t already). The above treats only the most common preternatural creatures. Norwegian folklore also encompasses the folk, the religious figures, and a great many animals that only a thought for the word count of this article, and a very guilty conscience, has prevented me from writing about. If you want to read the rest, then please take a look at my blog, norwegianfolktales.blogspot.com, where I post all the tales, as I get around to translating them.

Recommended Books from #FolkloreThursday

Endnotes

[1] It was Gypsy Thornton who got me thinking about the rôle of luck in Askeladden’s adventures.

[2] There is a common idea that trolls turn to stone in the sunlight, and Tolkein’s (literary) trolls certainly did, but I have yet to find a folk narrative in which the troll turns to stone. Such a narrative may well be Out There Somewhere, but as yet, I have not read it.

[3] A tip of the hat here to G.H. Finn, who first made the connection of the tail with the hulder-folk.