Merlin, the Mage, slept in the land on two portentous occasions: once leading up to the birth of Arthur; the second just before, and well beyond, the death of the Once and Future King. Each time there was a mighty mythical beast involved – the Afanc and the Red Dragon.

The grass was crisp underfoot, still glittering with the morning’s frosted dew. Gathering mists drifted over pastures, snaking amongst the boughs of ancient trees. Bare branches silhouetted against the blue and peach blush of winter sunset in the western sky or framing the full wolf moon rising to the east. “Don’t you see, all around you, the Dragon’s breath?” That line, spoken by Nicol Williamson as Merlin in Excalibur, John Boorman’s Arthurian epic of 1984, sprang to mind. How appropriate as we descended a long curve of uneven stone steps, all the more treacherous as the freezing fog followed to slick them with a thin film of fresh ice. We were entering the Fairy Glen, a chasm between two worlds, steeped in Welsh folklore where, it is said, ‘wild’ Merlin hermitted himself away to recuperate after the magical exertion of facilitating the birth of Arthur…

Here, the River Conwy tumbles between the cliffs of a deep gorge, cool in perpetual shade. Fairy Glen is an evocative, magical site. A place of pilgrimage for the Romantic poets, in search of ‘the sublime’, and for later generations of intrepid tourists venturing out from the nearby town of Betws-y-Coed to explore the rugged Snowdonian landscape. Often visitors will attempt to tap the magical energies by knocking votive coins into the deadwood of a ‘wishing tree’, a traditional ritual hoped to heal minor ailments and ease joint pain. When the conditions are right, it is said that the songs of fairies can be heard in the musical echoes of torrid waters as they foam, splash, and trickle among moss-topped boulders, crazed with gleaming quartz.

In the twilight, when it is neither day nor night, the fairies may sing a variety of songs, each with a different meaning or outcome. Their sweetest evensong can seduce the visitor into staying long after sunset when the glen becomes a passageway to Annwn, the Celtic underworld, home of Gwragedd Annwn, the Welsh lake maidens. To hear their most mournful madrigal means impending doom, but if one stops and listens respectfully, they may change their tune to one of cheer and good fortune. If any lyrics can be discerned, they may even share magical secrets (yn Cymraeg, of course) or foretell the name of one’s true love.

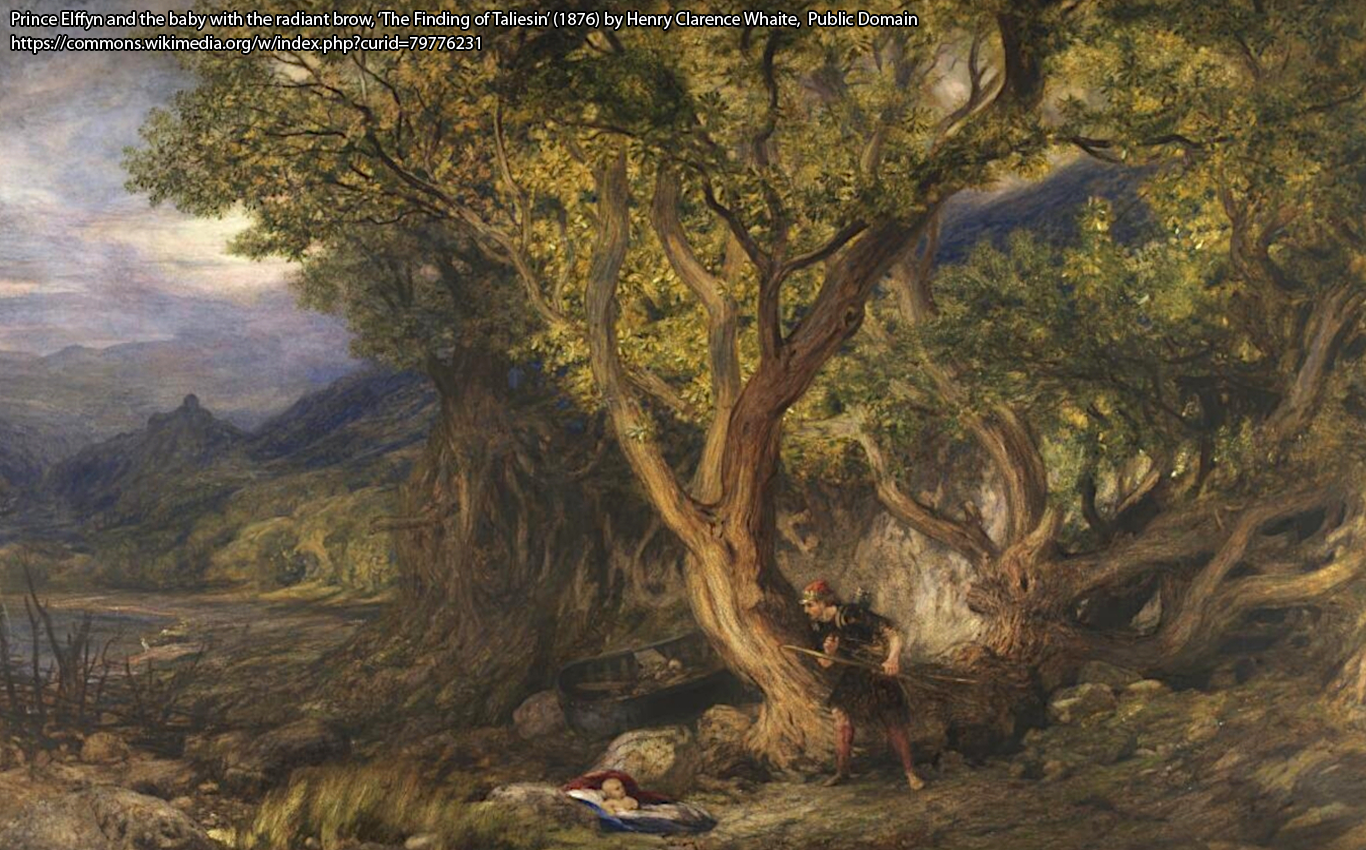

In Arthurian myth, it is this nearness of Annwn that attracted Merlin to the bend in the river now known as Fairy Glen. After casting the glamour to allow Uthor Pendragon to lie with Igrayne, wife to the Duke of Cornwall, Merlin was drained and driven part mad. For the safety of himself and others, he hid away from the human world. The same stretch of river was already home to a fearsome Afanc – a mighty river beast often described as a giant beaver, sometimes a water-dragon, and in some tales, it assumes humanoid form. Merlin befriended the creature, imbued it with magical powers, and trained it to guard his secret cave where he would hide for nine moons. Merlin’s period of dormancy parallels the gestation of the child who would be the future king of Albion. In this way, their destinies are entwined, Arthur’s birth coinciding with Merlin’s rebirth to herald a new age.

The periodic flooding of the Conwy Valley was blamed on the Afanc. It was said to build dams in much the same way as beavers do, only out of huge tree trunks wedged between the cliffs of the Fairy Glen, slowing the flow of the river. However, at times it would become restless and go on a rampage, sundering its dam to venture downriver on the flood surge. After such floods, felled trees would be found along the course of the river, bearing the gnaw marks of its giant incisors. On our recent research trip down into the Fairy Glen, we were lucky enough to find one such tree, evidence that somewhere upriver, a surviving Afanc still dwells.

However, there is a more pragmatic explanation for the distinctive marks. Fallen trees, carried downriver from the highland, are systematically stripped of their branches as they are rolled and dragged over rugged river boulders by the force of the torrent. When they reach the narrow passage of Fairy Glen, they become jammed among the boulders. Other trunks and boughs may join them until a logjam resembling a big beaver dam is created. As the weight of water builds above, these logs will be rocked over the rocks, seesawing and rolling before eventually being pushed onward. Such action may well result in the distinctive pattern of wear and tear that, with just a little imagination, could be taken as marks left by the gnawing of giant teeth.

The Afanc is the star of several traditional stories. Its legend takes different forms implying that, to the ancient Welsh, it was not a single creature but a species of mythological beasts just as dragons and unicorns. Its oldest tales link it closely with the formation of the landscape, particularly the waterways.

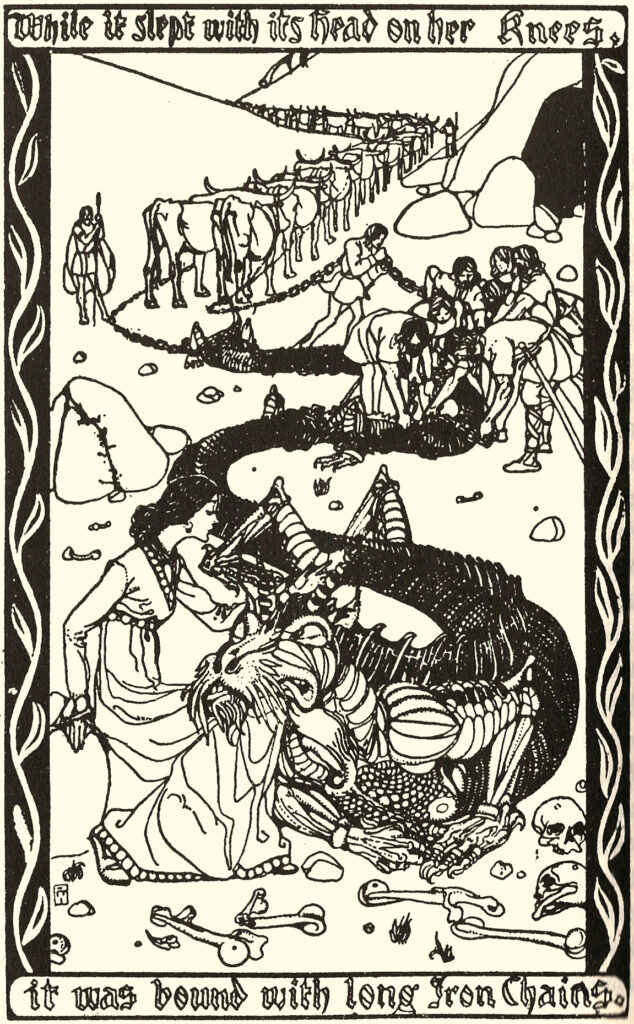

Before any humans came to Wales, the Afanc roamed undisturbed from lake to lake, its journeys creating the riverways. That’s until the first people arrived from across the sea. Their chieftain, the giant Hu Gadarn, brought with him the plough with great aurochs to pull it, carving new valleys where his people could settle and farm. The Afanc resented this intrusion and set about flooding these new valleys, sweeping away settlements and snacking on the settlers. So, Gadarn gathered his magician-priests, who were all blacksmiths, and each forged a length of magical chain with which to bind the beast. The maiden with the sweetest voice then sang the first song ever to be heard in the land of Wales, and this strange sound lured the monster from its lair. In some versions, it does not end well for the maiden. In others, the Afanc is simply lulled to sleep and enchained.

Gadarn then hitched his giant oxen and dragged the Afanc away to a distant lake, the great chains cutting new valleys as they went. The story goes that part-way along the arduous journey, the Afanc woke from its enchantment and thrashed so wildly that the oxen could barely complete their task, and one strained against the chains so much that one of its eyes popped out. A lake formed in the crater where the eye fell, still known locally as Pwll Llygad yr Ych, the ‘Pool of the Ox Eye’.

Eventually, the Afanc was released into a lake in the highlands of Snowdonia, where it was happy to stay. Which lake differs depending on the version of the tale, usually either Glaslyn or Cwmffynnon, and Afanc crop up repeatedly through later legends. One was slain down in Pembrokeshire by Sir Percival and buried in the long cairn known as Bedd-yr-afanc, the ‘Afanc’s Grave’. Another was dragged from Llyn Barfog, near Aberdyfi, by King Arthur and either slain or relocated. Not forgetting our aforementioned Afanc of Fairy Glen, which became Merlin’s fearsome familiar. The stories of Wales are part of the landscape, and the network of rivers and lakes connects the Fairy Glen with another important site in the legends of Merlin with stories that bracket his life.

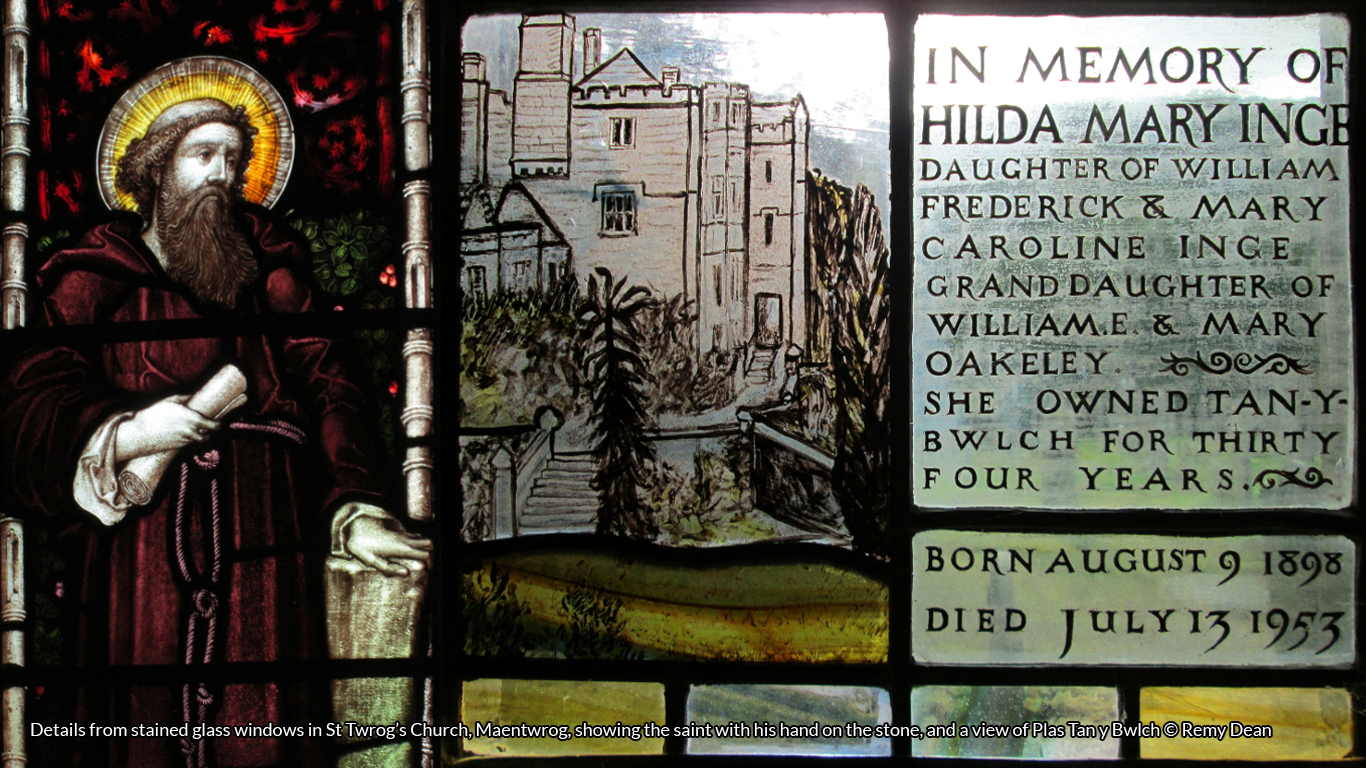

Less than ten miles away is the hill known as Dinas Emrys, most famous for its association with another mythical monster – none other than Y Ddraig Goch Cymru, the ‘Red Dragon of Wales’. The story spans centuries and begins with Lludd, an ancient chief of the Britons in early Roman times for whom London is named. His exploits include ending a succession of plagues and curses that befall his people.

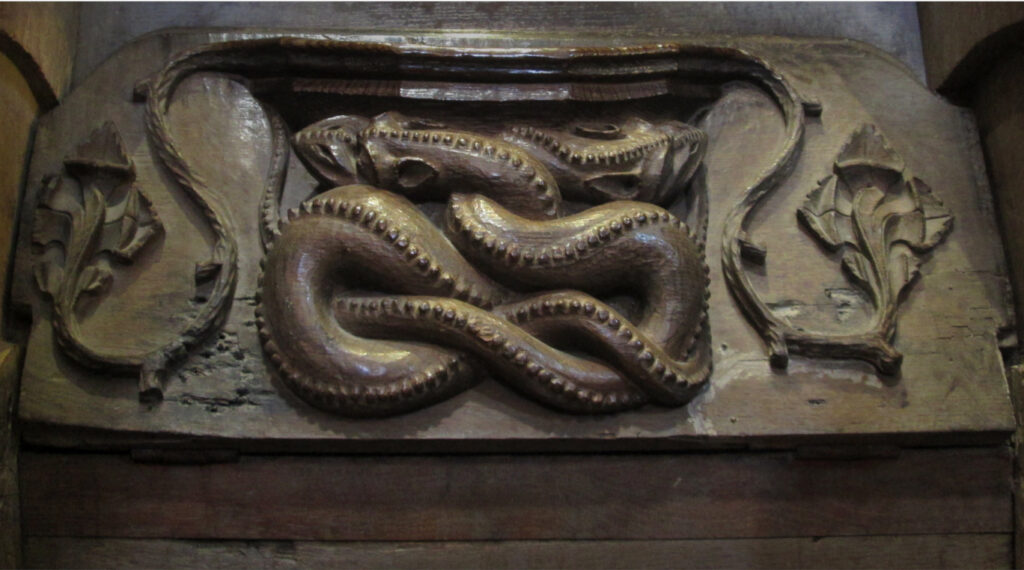

One curse is a shrieking that echoes across the land, so terrible that wherever it is heard, the crops wither, and animals drop dead or are rendered barren. He travels into the mountains of Wales, seeking the source of the hideous screams, and finds an ancient red dragon engaged in combat with a younger white interloper. Lludd subdues them both by luring them into a ‘great cauldron’ that he had built on the hill of Dinas Emrys and filled with mead. As they bite at each other, they cannot help but swallow gulps of the magical mead until they drink enough to stupefy them. Lludd then buries them where they sleep and erects a hall over them.

The area has a long history stretching back to Neolithic times, and the surroundings are dotted with clusters of hut circles. The hill provides a highly defensible natural outcrop and has been the site of hill forts since prehistoric times. When archaeologists excavated the remains of a twelfth-century tower on Dinas Emrys, evidence was found of an earlier medieval castle. A rounded hollow below the castle position had been artificially deepened with a pit to form a large chamber with wooden structures and a stone platform dating back to the fifth century. It may well have been an even earlier place of ritual significance and was probably used as the fort’s cistern. It could also be described as a ‘great cauldron’.

The red and white dragons had been sleeping for centuries when King Vortigern attempted to build his castle at the same site, but its walls repeatedly tumbled down before completion. He sought the advice of local Druids who told him that his problem could only be solved by a boy fathered by Y Tylwyth Teg, one of the immortal ‘Fair Ones’, yet born of a mortal woman. After searching far and wide, his knights finally found such a lad by the name of Myrddin Emrys, who will become better known simply as Merlin. Vortigern may well have intended to sacrifice the child, using the blood to consecrate the foundations, but the boy advised them to first dig underneath the castle. When they did, they uncovered the two entwined dragons, now awoken to resume their battle. It was their subterranean struggles that had been unsettling the foundations of the castle.

Merlin explained that the dragons will be bonded in their battle until long after the reign of Vortigern is over. He also said that one day the Red Dragon shall prevail, its victory heralding a new age when Britain would unite under one king. Of course, this can be read as a metaphor for the unrest of a divided land awaiting a good leader.

This is the earliest act of Merlin the Mage who endures to see Vortigern flee before the forces of the chieftain Ambrosius Aurelianus. Merlin then helps this rival to successfully construct a new keep on Dinas Emrys. Just to confuse matters, the chieftain was also known by a Welsh name, Emrys Wledig, so the hill fort is named after both the young warlock and this new king. In poetic retellings, they are one and the same person! Generations pass and Merlin becomes advisor to a line of successive chieftains, finally orchestrating the birth of Arthur, who would become the foretold one true king to unite all Britain. Merlin’s final act would also take place on the same site, and there is some conjecture that Arthur’s last stand also happened very nearby.

In legend, Arthur is killed by Mordred at the Battle of Camlann, the location of which scholars still enjoy debating. Several sites have been suggested, including Camboglanna, a Roman fort incorporated into Hadrian’s Wall, now known as Castlesteads. Down south, the area around Slaughter Bridge in Camelford is another candidate, mainly because it is near Tintagel, which attracts tourists due to its Arthurian embellishments. However, the slopes beneath Dinas Emrys hillfort lead down into Cwm Llan, the nearest open area suited to battle. Etymologically speaking, Arthur is thought to be derived from ‘Arth Fawr’, which is Cymraeg for ‘Great Bear’, a title applied to respected warriors and, to me, Cwm Llan sounds very much like Camlann!

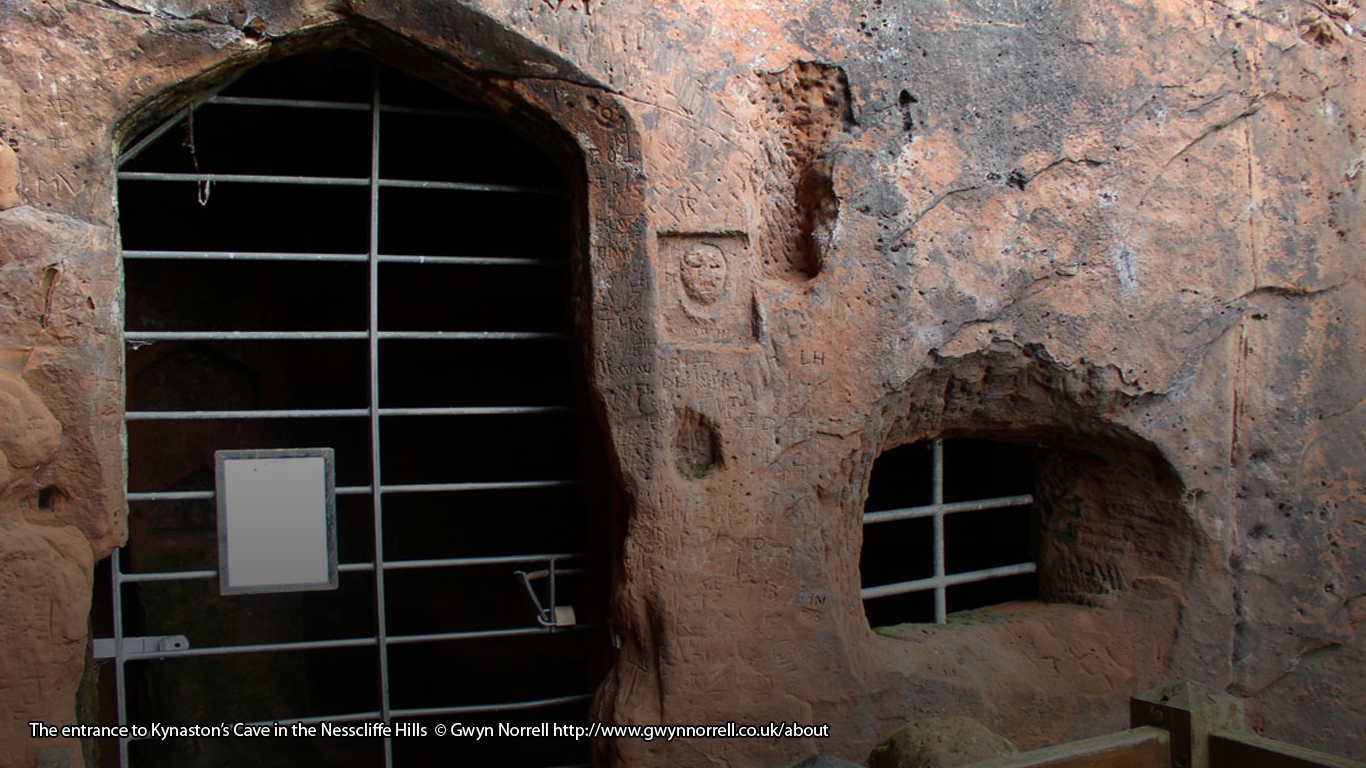

To lend supernatural aid in Arthur’s last battle at Camlann, Merlin descended into a crystal cave within the heart of Dinas Emrys where he crossed over into Annwn. Again, there are so many versions of this story that they can be mixed and matched to suit one’s sensibilities. Some say that after the battle, Merlin hid a magnificent horde of treasure in the cave, including the most valuable artefacts from Camelot. Maybe even the Grail. Some claim the so-called treasure is the secret knowledge of Merlin recorded in his magical grimoires. Others tell us that Merlin, himself, is the fabled treasure. He never returned and instead sleeps there still, dormant and awaiting another rebirth to coincide with the return of Arthur, the Once and Future King with whom his destiny is forever entwined.

References

Barker, L. (2008) Dinas Emrys. Available at Coflein, the online database for the National Monuments Record of Wales. (Accessed: 26 January 2022)

Dames, M. (2007) Merlin and Wales: A Magician’s Landscape. London: Thames & Hudson.

Dean, R. and Cariad, Z. (2020) This Part Four: This Fair Land, Wherein Dreams & Magics Meet. Snowdonia: The Red Sparrow Press.

Sikes, W. (1880) British Goblins: Welsh Folk-lore, Fairy Mythology, Legends and Traditions. London: Sampson and Low.

Snowdonia National Park (2016) Historic Landscapes from the Dark Ages to Modern Times. Available at: https://www.snowdonia.gov.wales/addysg-education/snowdonia-from-the-air/historic-landscapes (Accessed: 26 January 2022)

Thomas, W.J. (1907) The Welsh Fairy Book. Reprint. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 1995.

Tolstoy, N. (1985) The Quest for Merlin. London: Hamish Hamilton.

Westwood, J. (1985) Albion. London: Granada.