You cannot venture into the world of internet folklore without stumbling on the constant squabbles over what folklore is “right” and which version of a story is “correct”, yet the funny thing is that the fact these arguments exist means that people are not grasping how complex folklore is, nor understanding the forces that drive it. Folklore is change, it is variation, and it is an essential part of our culture that is happening all around us, all the time. As Folklorist Jan Brunvand puts it: “The juxtaposition of the terms ‘modern,’ ‘contemporary,’ and ‘urban’ and the word ‘folklore’ may seem contradictory to those who think of folklore as charming, obsolete, unsophisticated traditions passed along by the wheezing old gaffers and crackling crones in the backwoods village of bygone days” [1]. If a culture, or group of folk are currently alive, they are generating folklore which lives alongside them.

The word folklore was first recorded by William Thoms in an 1846 letter to The Athenaeum: Journal of Literature, Science, and the Fine Arts. While the periodical often dealt with ‘Popular Antiquities, or Popular Literature’ Thoms suggested “Folk-lore” as a collective term for this material that he believed: “would be most aptly described by a good Saxon compound, Folk-Lore, – the Lore of the People” [2]. Thoms intention with this letter was to encourage the periodical to continue to print such material; the stories of the folk, but to also understand the social importance of this material and the need for collecting and recording it.

It was not that folklore hadn’t existed before then; the Brothers Grimm by this time had been collecting German Folktales for years–their first collection, Kinder- und Hausmärchen (Children’s and Household tales) was first published in 1812. Over a hundred years earlier the French Charles Perrault had compiled a collection of French fairy tales, Histoires ou Contes du Temps passé: Les Contes de ma Mère l’Oye (Stories and Tales of the Past: Tales of Mother Goose) published in 1697, while some fairy tales can be found in collections as early as Giovanni Francesco Straparola’s 1551 Le Piacevoli Notti (The Pleasant Nights).

While Thoms lamented the fact that there had not been a Grimm brother to collate the history and mythology of the British Isles yet, he was still impressed by Jacob Grimms’ second edition of Deutsche Mythologie which Thoms described as “a mass of minute facts, many of which, when separately considered, appear trifling and insignificant, but, when taken in connexion with the system into which his master-mind has woven them, assume a value that he who first recorded them never dreamed of attributing to them”[3]. This is what Thoms was trying to get people to understand: it is not just the epic story narratives found in legends and fairy tales, but the collective works–anecdotes, wisdom, recipes, and customs–that all help to paint a picture of the real lives of the people of the times–people whose own histories are deemed unremarkable and unworthy of recording, people who get washed away with the sands of time.

While I wouldn’t be a folklorist without agreeing that the recording of this information is important and can yield fascinating truths about the people who share it and the lives they lead, arguably the greater value in folklore is not trying to find the one true source and recording it for posterity, but in analyzing the patterns that emerge in variation over time. As folklorist Jan Brunvand puts it:

“All true folklore ultimately depends on continued oral dissemination, usually within fairly homogenous ‘folk groups’, and upon the retention through time of internal patterns and motifs that become traditional in the oral exchanges. The corollary of this rule of stability in oral tradition is that all items of folklore, while retaining a fixed central core, are constantly changing as they are transmitted, so as to create countless “variants” differing in length, detail, style, and performance technique. Folklore, in short, consists of oral transmission in variants” [4].

While folklore is frequently infiltrated by fascist and racist agendas, those people do not even begin to grasp the fundamental concept of folkloric studies; the true value is in the change and variation, much of which stems from cross-cultural (or cross-folk) exchanges.

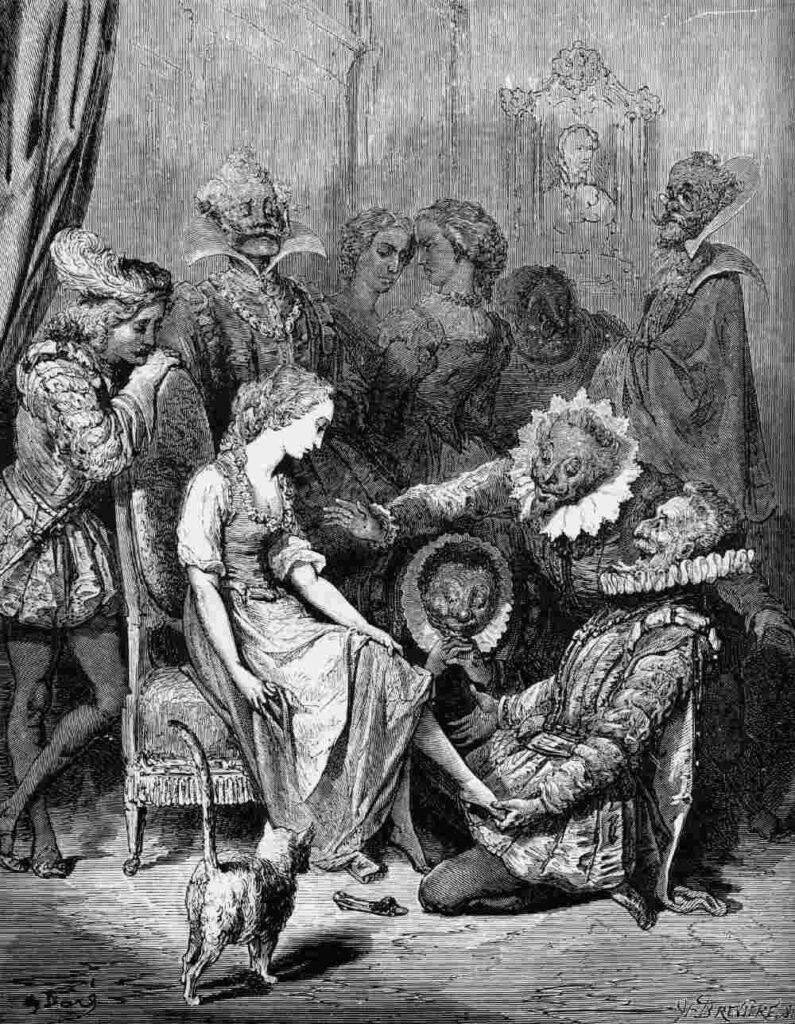

One perfect example of the folklore process is the story of Rhodopis recorded in 1st century B.C. by the Greek historian Strabo. Rhodopis was a Greek courtesan, living in the Egyptian city of Naucratis. One day while she was bathing, an eagle swooped down and stole one of her ruby red sandals he saw flashing in the sunlight. Gripping the shoe tightly in its talon the eagle flew off towards the capital of Memphis where the king was holding court outside his palace. As he flew overhead, the eagle dropped the sandal right into the lap of the king. Intrigued by the delicate shoe and its mysterious appearance, the king sends his men out into the countryside to find its owner. Eventually, the beautiful slave girl is summoned before the king and they were married [5]. Sound familiar–an impoverished girl who loses a shoe, and a royal who comes into possession of it and uses his soldiers to eventually reunite it with its owner; a beautiful girl who the royal figure falls in love with and marries–all elements that are centrally core to what we now recognize as the story of Cinderella.

There are countless variations of this central motif found worldwide. By 1893 Marian Roalfe Cox had already collected and published a study of 345 different variants of “Cinderella” [6], and that does not even begin to touch the countless variations that have blossomed since. As well as the Egyptian Rhodopis, there is the Chinese story of Ye Xian, a young girl who is gifted golden shoes by magical fish bones and eventually marries a sea king. In Belgium Pepelezka is aided by supernatural cow bones which provide her magical church clothes, and when she loses her shoe in the church crowd an admiring emperor’s son comes looking for the mystery girl. There are centuries of countless variations in countless cities of a similar tale, but the moralistic differences, the type of clothing she wore, the social gatherings she attends, the lifestyles in which she lives, and even the suitor that she marries, are all context clues which reflect the differences in the societies in which they are told.

Because of the origins of the discipline, folk is still often thought of by the narrow definition of European peasantry, or as “the nineteenth-century definition of the folk as illiterate, rural, backwards peasants [7]”. Most modern interpretations have moved away from this restrictive and Euro-centric definition towards a more inclusive description. Folklore is a global process that exists in all groups of people that have a defined commonality that creates a sense of belonging and tradition. “The term ‘folk’ can refer to any group of people whatsoever who share at least one common factor. It does not matter what the linking factor is–it could be a common occupation, language, or religion–but what is important is that a group formed for whatever reason will have some traditions which it calls its own [8]’. So, who are the folk? We are the folk. All of us that participate in societal groups and don’t have the power or influence to directly affect social changes as individuals are the folk and are generating folklore.

Jan Bruvand posits that “We are not aware of our own folklore any more than we are of the grammatical rules of our own language” [9] and that to a large degree is why people only see folklore as something from the past. We are all constantly participating in the creation of folklore, we just are so embedded in the pattern that it is harder to see the picture. If we look at another, more recent, example of folklore; the urban legend, we can see the folkloric process at play here too. As a child growing up in the 80s/90s I had heard tales and told tales of alligators in the sewers in NYC. Sewers were already dark, mysterious, and dangerous places, adding in some alligators really gave them a sense of awe; this was a story to tell all your friends! Was this the same folkloric processes, and same sense of exhilaration that Victorian age school children felt telling their school chums about a giant black sow that had fallen into the sewers beneath Hampstead and created generations of interbred cannibal pig monsters deep below? Did the story from De Natura Animalium written in 2 A.D. about a sewer dwelling monstrous octopus that crawled through the sewers accessing cellars and stealing pickled fish pass among the children of ancient Rome? [10]

As we embrace the idea of folklore as a process of change, there is one more quote I want to consider: “The folklore process is a continuing and infinitely flexible one in which traditional forms may decline, persist, or become more widespread, depending on their relevance. Additionally, folklore may manifest itself in completely new forms in response to developing social circumstances” [11]. Many folklorists cling to the idea that folklore must be oral, and historically this has made sense. Writing skills were initially uncommon, but even as they became common access to mass modes of transmission were still out of touch for most regular folk. The internet and word processing has changed that. You can easily edit a story as you pass it along to your hundreds of friends with a few clicks of a button. When something surges in internet popularity, we call it going viral–the idea of fast change, transmission, and adaption. We call the captioned pictures we trade in response to current events memes–defined in the Merriam Webster Dictionary as: “an idea, behavior, style, or usage that spreads from person to person within a culture” [12]. The very fact that people started randomly faxing each other chain letters and jokes in the brief window that fax machines were common demonstrates how adaptive folklore can be to technology.

Folklore is a process of variation and change in our culture, and it grows alongside it. While it should be preserved as an important part of our growth as humanity, and as a record of our history, we also must allow it to live, breathe, grow, and adapt alongside us. Folklore is our unfiltered reaction to the events that are happening to us, and the cultural and social forces that are applied to us. It is an expression of our creativity and wonder, and as a folklorist I am always waiting and watching to see where, when, and how it will bloom and flourish next.

References

[1] Brunvand, Jan. The Vanishing Hitchhiker: American Urban Legends and their Meanings. New York: W.W. Norton. 1989. Print. Page xi

[2] Winick, Stephen. The Two First “Folk-Lore” Columns.

[3] Winick, Ibid.

[4] Brunvand, ibid. Page 3.

[5] Green, Roger Lancelyn. Tales of Ancient Egypt, London: Penguin, 2011. Print. Page 207-212.

[6] Cox, Marian R. Cinderella: Three Hundred and Forty-Five Variants of Cinderella, Catskin, and Cap O’Rushes. London: Folk-lore Society, 1893. Print.

[7] Dundes, Alan. Interpreting Folklore. Bloomington: University of Indiana Press. 190. Print. Page 6

[8] Dundes, Ibid, Page 6/7

[9] Brunvand, Jan. Ibid. Page 1

[10] MythCrafts. Sewer Monsters: From New York City to Ancient Rome.

[11] Seal; Graham. The Hidden Culture: Folklore in Australian Society. Perth: Black Swan Press 1998. Print. Page 5

[12] Merriam- Webster Dictionary. Meme.