Anasyrma, or the lifting of one’s skirts to expose genitalia, has been used throughout history and mythology as a method to ward off evil and shame men for their actions. Arguably, the viral Pussyhat™ from the 2017 Women’s March that was worn by thousands of women around the globe can be seen a resurfacing of that symbolism in an evolution of protest folklore for the modern day.

The 2017 Women’s March was a worldwide protest held on January 21st, 2017. According to organizers the aims of the march were for the “Protection of our rights, our safety, our health, and our families – recognizing that our vibrant and diverse communities are the strength of our country”. Fuelled by anger arising from the inauguration of President Donald Trump, a man with a history of offensive behaviour towards women, the 2017 Women’s March was the largest single day protest in US history with an estimated 3-5 million participating nationally, and 7 million people throughout the globe.[i] This anger had also been intensified by a recently released tape of Donald Trump bragging about sexual assault where he infamously said:

“You know I’m automatically attracted to beautiful. I just start kissing them. It’s like a magnet. Just kiss. I don’t even wait. And when you’re a star, they let you do it. You can do anything… Grab them by the pussy, you can do anything.” – Donald Trump

The symbolic Pussyhat™ that was worn by many of the marchers was created by two friends, Jayna Zweiman and Krista Suh, as a direct protest against Donald Trump’s offensive comments. They “conceived the idea of creating a sea of pink hats at Women’s Marches everywhere that would make both a bold and powerful visual statement of solidarity” with the aim of publicly shaming Donald Trump and those that voted for him. Helped by designer Kat Coyle they freely distributed a simple pattern with pussy cat ears to symbolize the vagina that Donald Trump felt he had the right to non-consensually grab.

Historically the mysterious power of a woman’s vagina was believed to be so strong that simply possessing one equipped women with a great natural power source. In many cultures, the vagina has been revered as a powerful object; psychoanalyst Géza Róheim believed that “all magic is derived directly or indirectly from the female sexual organ”,[ii] while Pliny the Elder espoused the power of the vagina in Natural History where he wrote that:

“There is no limit to the marvelous powers attributed to females. For, in the first place, hailstorms, they saw, whirlwinds, and lightning even, will be scared away by a woman uncovering her body while her monthly courses are upon her. The same, too, with all other kinds of tempestuous weather; and out at sea, a storm may be lulled by a woman uncovering her body, merely, even though not menstruating at the time”.[iii]

It is this idea of uncovering a woman’s body to produce an apotropaic effect and adverting evil or bad omens that is known by the Ancient Greeks as anasyrma (also translated as ana-suromai) and is “derived from a Greek word meaning literally ‘to raise one’s clothes’”.[iv]

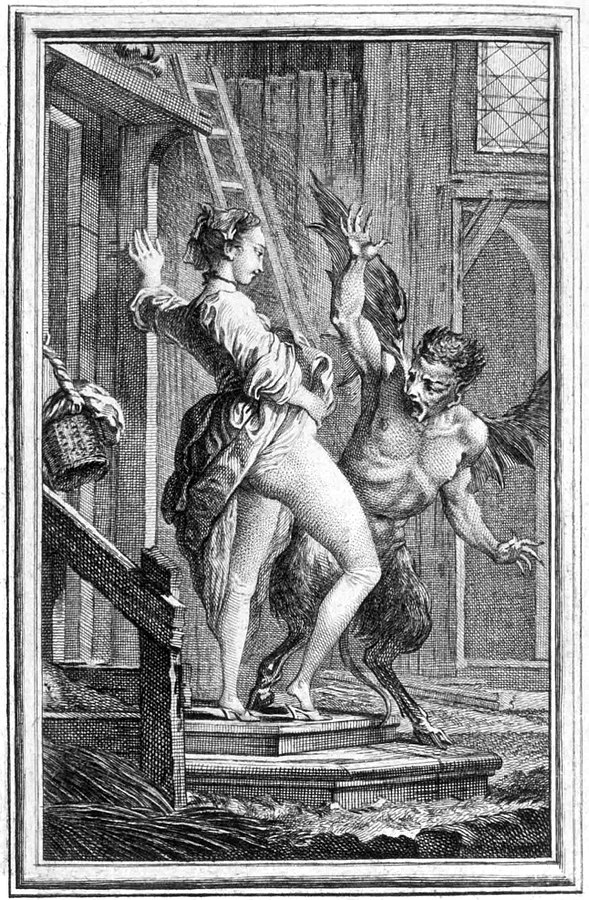

In The Story of V, feminist author Catherine Blackledge collects examples where the vagina is shown to have a apotropaic effect as she recounts how a traveller in North Africa recorded lions running scared from women who were lifting their skirts, how folkloric legends from Russia advocated female genital displays as a method to stave off bear attacks, and a seventeenth century European belief that raising one’s skirts could frighten off the devil himself.[v] Lions, bears and the devil represent some of the greatest fears of humanity; things that have the power to destroy humans and highlight human frailty and vulnerability, yet the mere sight of the female vagina had the power to vanquish them all.

The Sheela-na-gig, an architectural grotesque carving that represents a woman holding open her exaggerated vulva to display is one such example. This carving is found throughout Ireland, Great Britain, and mainland Europe, commonly perched above a door or window on the facade of castles and churches from the eleventh and twelfth century. While the Sheela-na-gig may have also been assigned a fertility role, many scholars also believe that they served an apotropaic function to guard against evil entering the building. In Barbara Freitag’s book Sheela-na-gigs: Unraveling an Enigma, she uses Celtic scholar Anne Ross’s work on these carvings to help explain how the Sheela-na-gigs came to adorn the outsides of Christian churches:

“To explain how they came to be built into Christian churches, Ross furthermore assigns an evil-averting significance to them, based on the general and wide-spread belief that the exposure of the genitalia acts as a powerful apotropaic gesture”.[vi]

As well as using it to apotropaic effect, women could also use the art of anasyrma to wield power over men and use it as a form of protest designed to shame men for their actions. This usage occurred in the mythology of Bellerophon, the great hero and son of the sea god Poseidon. Astride his flying horse, Pegasus, Bellerophon had already managed to defeat the monstrous Chimera but when King Iobates refused to credit Bellerophon with this deed, Bellerophon marched on his palace intending to destroy the kingdom. Poseidon aided him and sent giant waves rolling towards the palace, and Bellerophon flew in to attack knowing no man could defeat him. The Xanthian women, aware of the carnage that would be unleashed, came rushing out and hoisted their skirts to the waist. Despite his bravery in battle, the sight of these women was too much for the hero Bellerophon and he turned tail and fled, taking the rolling waves with him.[vii]

The Irish hero Cú Chulainn faced a similar sight when he threatened to do battle with his own countrymen. None of Cú Chulainn’s friends or advisors were able to convince him not to go war, so it was up to the women to stop his plan. Led by their chieftainess, Scannlach (‘the Wanton’) the women waited naked on the path Cú Chulainn would cross on his way to battle. As he came across the women he was shamed by the sight and curled up and hid in his chariot in as his men led him back to his palace.[viii]

The ancient Greek historian, Plutarch, recorded a similar instance of anasyrma in his treatise on the “Bravery of Women” where he described how the Persian army, fleeing for their lives, were humiliated into returning to their battle by the sight of their women lifting their skirts and saying ‘Whither are you rushing so fast, you biggest cowards in the whole world? Surely you cannot, in your flight, slink in here whence you came forth.’ The Persians were mortified by the shaming of their cowardice and returned directly to battle.[ix]

The idea of using the vagina to shame men and their actions is one that is still used today in parts of Africa. In recent years the powerful impact of these beliefs was demonstrated in a protest against a large oil corporation’s exploitation of the land and the communities of Nigeria. In June 2002 hundreds of unarmed Nigerian women managed to hold 700 hundred men prisoner and shut down oil production for over a week with nothing but the threat of exposing their genitals. Sokari Ekine, the International Coordinator of the Niger Delta Women explained that the men believed that they will go crazy, suffer from misfortune or become impotent, so the simple threat was enough to keep them compliant and captive.[x]

So, can we connect the pink Pussyhat™ from the 2017 Women’s March to the act of anasyrma? These hats were designed to be symbolic representations of the vaginas that Donald Trump felt he had free reign to grab without consent and the protest was designed to use the hats to publicly shame him and the behaviour he exhibited, much like anasyrma has been used in the past. In a legislative world, where displaying genitals in public is an arrestable offence that can result in anywhere between a $500 U.S. fine and potentially a 90 days jail term, it makes sense that this powerful form of protest would evolve to fit the current environment.

This article is based on a paper presented by the Author at the Popular Culture Association National Conference in Washington DC on the 19th April 2019.

[i] Chenoweth

[ii] Otero 283

[iii] Pliny 28.23

[iv] Blackledge 12

[v] Blackledge 8-9

[vi] Freitag 33

[vii] Graves 240

[viii] Dunn 77

[ix] Plutarch I.V

[x] Vidal & Branigan

Blackledge, Catherine. The Story of V: Opening Pandora’s Box. Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2003.

Chenoweth, Erica. “This is what we learned by counting the women’s marches”. The Washington Post. 17 February 2017,

Dunn, Joseph (trans). The Ancient Irish Epic Tale Táin Bó Cúalnge. David Nutt, 1914.

Freitag, Barbara. Sheela-na-gigs: Unravelling an Enigma. Routledge. 2004.

Graves, Robert. The Greek Myths. Penguin Books, 2017.

Otero, Solimar. “Fearing Our Mothers: An Overview of the Psychoanalytic Theories Concerning the Vagina Dentata Motif F547.1.1”. American Journal of Psychoanalysis 56, no. 3, 1996, pp. 269–288.

Pliny. The “Natural Histories” of Pliny the Elder: an Advanced Reader and Grammar Review. Translated by Chambers, P. L. U of Oklahoma P, 2012.

Vidal, John, and Tania Branigan. “Nigerian Women Take on Chevron Texaco.” The Guardian, 22 July 2002, www.theguardian.com/world/2002/jul/22/gender.uk1