Some pertinent advice here. How do you rid yourself of a wife who no longer pleases you? Sell her, of course.

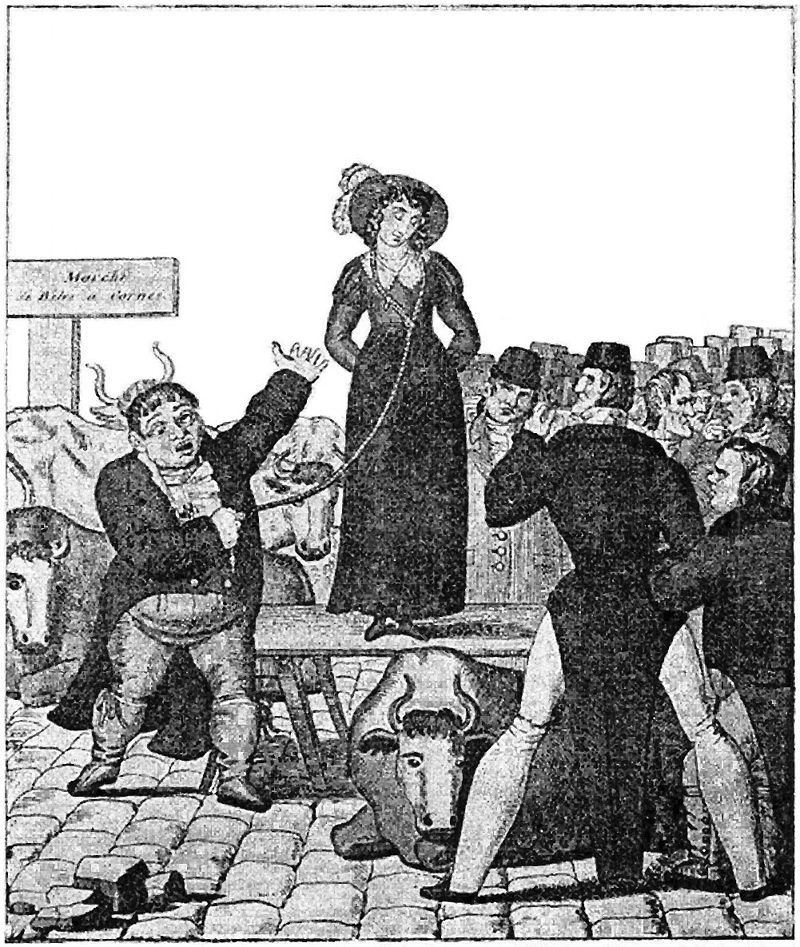

The practice of a husband selling his wife in the open market with a rope around her neck so that she might be led away, as if she were no better than a piece of livestock, would seem to be a throw-back to an unpleasant aspect of medieval feudalism and women’s subservience to men. It was a simple way of ending an unsatisfactory marriage by mutual agreement when divorce was a practical impossibility for all but the very wealthy. After parading his wife with a halter around her neck, arm, or waist, a husband would publicly auction her to the highest bidder. Wife selling provides the backdrop for Thomas Hardy’s novel The Mayor of Casterbridge, in which the central character sells his wife at the beginning of the story, an act that haunts him for the rest of his life.

Although the custom had no basis in law and frequently resulted in prosecution, particularly from the mid 19th century onwards, the attitude of the authorities was equivocal. At least one early 19th century magistrate is on record stating that he did not believe he had the right to prevent wife sales, and there were cases of local Poor Law Commissioners forcing husband to sell their wives, rather than their having to maintain the family in workhouses.

How long did wife-selling last?

This practice was still known in Hereford well into the 19th century. In 1802 a butcher sold his wife by public auction in Hereford market. The unfortunate woman – or perhaps she was fortunate in the change of circumstance – changed hands for one pound, four shillings, and a bowl of punch.

In 1900, a woman of ninety years recalled, in a piece of oral history, having seen the sale of a wife on more than one occasion. This is one sale that she described in her own words. The casual acceptance of this practice – by all concerned – is the most interesting aspect of it. Here is the eye-witness’s view of the proceedings, with all its drama:

At one end of the pig market in Hereford a crowd of people had gathered as I passed by. In the centre stood a woman, smartly dressed in a good hat and a red cloak. Her eyes were downcast. Around her neck was a rope, the end held by the man standing next to her.

‘What has she done?’ I asked, thinking that the woman was about to be hanged for a crime.

‘She has done no good, depend on it,’ one of the crowd replied, ‘or the maister wouldn’t want to sell her.’

The crowd laughed. The bidding started.

‘I’ll give a shilling,’ a man called Jack called out.

‘Well done Jack. That’s eleven pence more than I would give,’ another man called. ‘It’s too much boy, too much.’

Jack stood firm. ‘No. I’ll give a shilling, ‘and you ought to be thankful to get rid of her at that price, maister.’

‘Well I’ll take it,’ the maister replied, ‘though her good looks ought to be worth more than that.’

‘Keep her then,’ the bystanders shouted. ‘Keep her for her good looks.’

‘No, I’ll not keep her. Good looks won’t put the victuals on the table without willing hands.’

‘Well here’s the shilling,’ Jack offered, ‘and I warrant I’ll make her put the victuals on the table for me, and help to get it first.’

Jack held out the shilling and spoke to the woman.

‘Be you willing Missis to have me, and take me for better for worse?’

‘I be willing,’ she said without hesitation.

‘And be you willing to sell her for what I bid, maister?’

‘I be willing,’ the maister said, ‘and will give you the rope into the bargain.’

So Jack gave the maister his shilling and the wife changed hands.

All this happened with no outcry from the crowd that accepted the proceedings. If anything it was a casual source of entertainment, of masculine amusement. Nor does the wife appear to be particularly distressed. Perhaps she considered the change in husband a good bargain. Perhaps Jack had caught her eye! We shall never know.

It was not the only wife-sale at which our eye-witness was present. She, too, accepted it as part of the market scene. Although the passage of time might have embellished her memories and loaded them with artistic licence, we must think that it was not uncommon in rural communities.

I don’t think it is part of the culture of Herefordshire today …

Books by Anne O’Brien

References & Further Reading

Leather, E. L. 1912. The Folklore of Herefordshire