On the evening of 11th December, Icelandic children place shoes on the sills of their windows, before they go to bed. That night, the first of the Yule Lads will pay each good child a visit, and leave a gift. Bad children receive potatoes. Each subsequent night before Christmas, the ritual is repeated, each time with a new Yule Lad leaving a gift or a potato.

This modern form of the tradition was reformed from old Icelandic practices, and reintroduced into society through Jón Árnason’s folktales, published in 1862, and thereafter in the Christmas poem “The Yuletide-lads” (1932) by Jóhannes úr Kötlum. It is in this poem the number of Yule Lads is set at 13. Their names reveal the natures of these tricksters:

| Icelandic | English | Trick |

| Stekkjastaur | Sheep-Cote Clod | Worries sheep |

| Giljagaur | Gully Gawk | Hides in gullies, waiting for opportunity to steal milk |

| Stúfur | Stubby | Steals the crusts of pies |

| Þvörusleikir | Spoon-Licker | Licks wooden spoons |

| Pottasleikir | Pot-Licker | Licks pots |

| Askasleikir | Bowl-Licker | Licks bowls |

| Hurðaskellir | Door-Slammer | Slams doors |

| Skyrgámur | Skyr-Gobbler | Steals skyr |

| Bjúgnakrækir | Sausage-Swiper | Steals sausages |

| Gluggagægir | Window-Peeper | Looks in at windows for things to steal |

| Gáttaþefur | Doorway-Sniffer | Sniffs at doorways for laufabrauð |

| Ketkrókur | Meat-Hook | Steals meat by means of a great hook |

| Kertasníkir | Candle-Stealer | Steals and eats (tallow) candles |

The number of Yule Lads has varied through their history, however. Sometimes there are more, as many as 50; sometimes fewer.

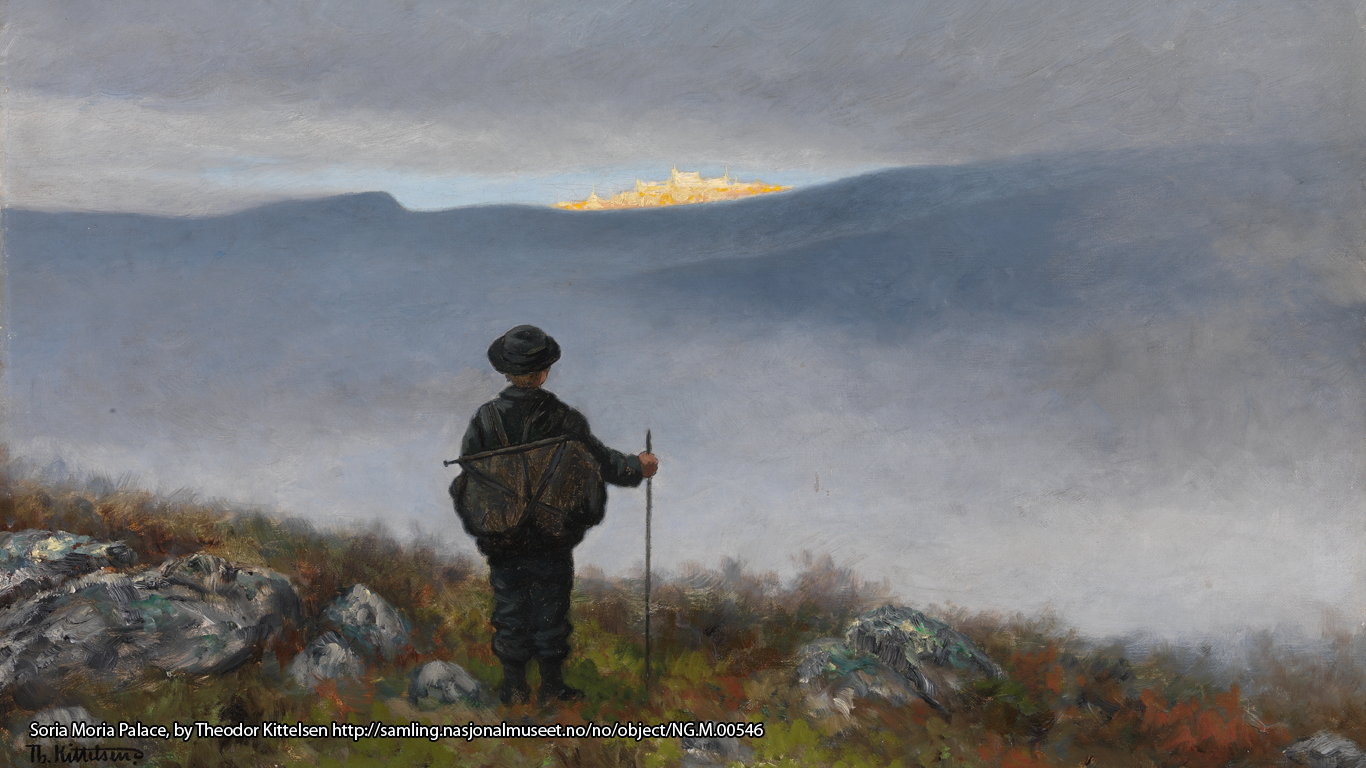

The degree of their malevolence has also changed over time. These days, the Yule Lads are widely regarded as being as benevolent as Santa Claus; and a potato is not the worst punishment for ill behaviour. Historically, however, the Yule Lads have been regarded as tricksters, who “came down before Christmas to steal Christmas food rations and torment people with their pranks.” The threat of the Yule Lads was used to intimidate children into good behaviour during advent. In fact, “by 1746 they became so bloody that the Danes, who ruled over Iceland at that time, issued a law banning stories used for scaring children into good behavior.”

Grýla

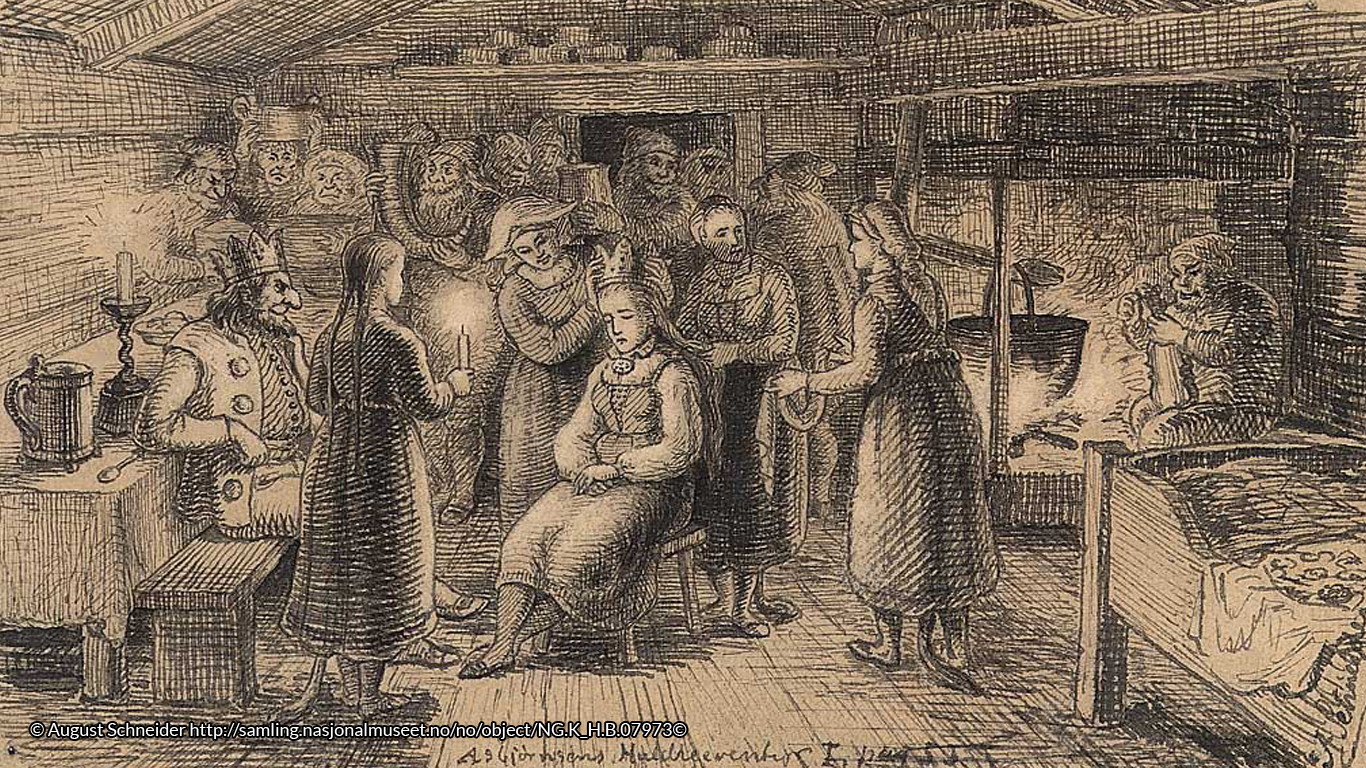

The Yule Lads are all brothers. Their mother, Grýla is a bloody troll, as Terry Gunnell notes:

One of the oldest Icelandic folk traditions — if not the oldest — is that connected with the figure of Grýla, the ugly, ever-ravenous mother of the Icelandic jólasveinar, who, in league with the dreaded jólaköttur [the Yule cat], annually terrorises the under-six year-olds when she descends from the mountains at Christmas in search of badly-behaved children to bundle into her sack.

There have been numerous attempts at banishing Grýla from Christmas; but she is a tenacious old troll: “Despite the recent efforts of certain parties to ease the fears of the young by announcing Grýla’s death, the ancient ogress seems to hang on interminably. She is not so easily persuaded to give up the ghost.”

First named in Sverris Saga (approx. 1300), Grýla has been recognised by Icelanders since the 13th century; “there seems little question that in Iceland at this time, her name was synonymous with something threatening.” However, Gunnell finds evidence of Grýla’s name being associated with animal skins, costume, and (cursed) folk dance. She is connected with folk entertainment. He also links the Icelandic troll with Bovi, a Germanic figure who leads a devilish dance, “travelling through the countryside” of Germany and/ or Orkney. Bovi is known in Ireland as a “‘possessed’ straw figure that was carried by certain Danish women as part of a ring-dance which had been designed to entertain a pregnant friend.” Elements of all these traditions are still familiar in the Nordic lands.

The Oskoreia

In Scandinavia, the Oskoreia (Norwegian) or Odens jakt (Swedish) is a variant of the wild hunt that is often heard at Yuletide among the farmsteads. There are various traditions connected to this superstition. A turn in the weather, accompanied by the barking of dogs signalled the hunt; and painting a cross in pitch on the doors of your farm buildings would protect you and your animals from being taken as it passed. The fear of meeting the hunt was so great that in certain places, people going to and from church during the Christmas period would carry with them a piece of steel to throw before the leader of the hunt, and bread to feed his hounds.

Lussi Langnatt

Lussi Langnatt is another tradition that may be related to Grýla. People would keep indoors on the night between 12th-13th December (the longest night of the year in the Julian calendar), for fear of meeting the Oskoreia, and the farmstead would be visited by Lussi, a tempremental spirit who wished to ensure that all the spinning and threshing was done before Christmas. The Christmas baking should also have begun. If Lussi was not satisfied with what she saw, she might come into the house down the chimney, or even pull down the chimney to express her displeasure. Although this tradition has mostly died out, thanks to the church’s imposition of the celebration of St. Lucy, which is still widely observed in Scandinavia, there is an odd remnant: the lussekatt buns that are baked and eaten on 13. December, a way of demonstrating that the chores are completed, and the Christmas baking begun.

The Yule Goat

The Scandinavian Yule goat also appears to be related to the “‘possessed’ straw figure” mentioned above in relation to Bovi, and thus Grýla. There are several traditions concerning the goat. The figure has been seen as a way of marking the end of the farming year; it has been taken around the farmsteads by masked people dressed in skins, who would play and dance in return for food, drink, and Christmas fare; and it has been used in dramatisations of the Oskoreia. In every one of these traditions, we catch a glimpse of Grýla.

The Yule Lads

And thus we come back to the Yule Lads. Their behaviour in their older format mirrors that of the mother, who may also be discerned in many of the mid-winter/ Yule/ Christmas traditions in the Nordic countries. It would appear, that this ancient, threatening troll Grýla is, as Gunnell states: “a shared myth of some kind relating to an adult-created bugbear that in later times (in Iceland and the Faroes) was used to frighten children.” However, since such is now banned in Iceland, the Yule Lads have assumed a friendlier role.