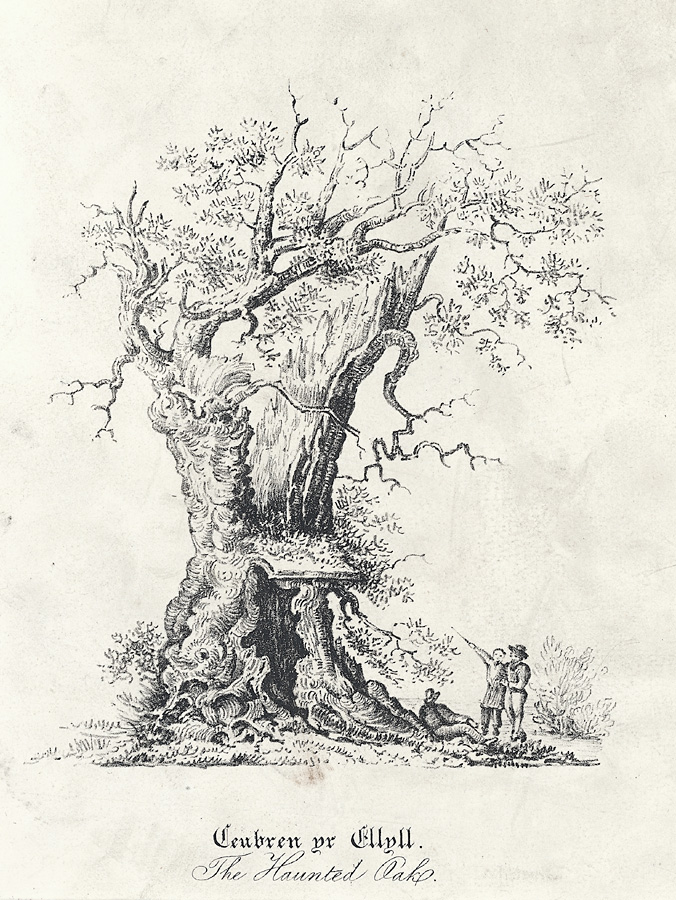

Two famous folktales of North Wales feature the discovery of skeletons in hollow, lightning-struck oaks. There is the Nant Gwrtheyrn ‘Haunted Oak,’ associated with the tragic talethe of Rhys and Meinir, and the Nannau Estate’s ‘Demon Oak,’ from the story of Owain Glyndŵr and Hywel Sele.

The Nant Gwrtheyrn tale is certainly a romantic fiction, bearing so strong a parallel to ‘The Legend of the Mistletoe Bough.’ This story tells of a bride playing a game of hide-and-seek on her wedding day, as part of the ‘bride-quest’ tradition, who proves to be so good at the game that she is never found. The groom is driven mad by a life of loneliness and grief, believing his bride chose to run away, until her skeleton is finally discovered, upon which the now old man promptly dies of shock and horror. Variations of the tale have her accidentally locked in a cellar, in a chest in an attic, in an abandoned tower room, and so on. The story is associated with numerous old mansions and castles across Europe, from southern Italy to Scotland. It was also the inspiration for the 1830s song of the same title, re-told in various short stories, adapted into three film versions (1904, 1923, & 1926) and is referenced in Alfred Hitchcock’s ‘Rope’ (1948). In the Nant Gwrtheyrn version, it is a hollow oak that entraps Meinir, the hapless bride-to-be, and Rhys is the groom who endures decades of grief until lighting splits open the oak to reveal Meinir’s skeleton, still wearing her wedding dress.

By contrast, the story of the Nannau Oak is interwoven with verifiable history and has left several tangible artefacts as a record of its existence. As is the case with oral traditions, folklore and historical fact certainly overlap, though it is often difficult to discern where one ends and the other picks up.

The Derwen Ceubren yr Ellyll, which translates as “The Hollow Oak, Haunt of Demons” or “The Blasted Oak of Spirits” and is sometimes simply called “The Skeleton Tree,” was certainly a real tree. It is referenced as far back as the fourteenth century, and rumours of it reach even further back. Its long story is a dark and terrifying one, and does not end when the ancient tree was finally felled by the fierce summer storm of July 1813…

“Pale lights on Cader’s rocks were seen,

And midnight voices heard to moan;

‘Twas even said the Blasted Oak,

Convulsive, heaved a hollow groan:”

Just north of the Welsh town of Dolgellau is the small lake of Llyn Cynwch, which features in local mythology. It is said to be the location of a sunken palace of pure white marble, home to the King of the Fair Ones, and that upon its banks a fearsome Wyvern was once slain. The old oak stood between this lake and the peak of Moel Offrwm, where two ancient hillforts testify a long history of settlement in the area. A particularly steep escarpment overlooking the site is known as “The Place of Sacrifice,” and the tree stood in or near “The Field of Succour.” Who sacrificed who is unclear, but given that both forts date back to the Iron Age and one was still used into the Roman era, it has been surmised that Druids may have sacrificed captured Roman invaders there, presumably by flinging them from the cliffs. Of course, oak is the sacred tree of the Druids and so the tree may well have been part of the grove used as their ‘temple.’

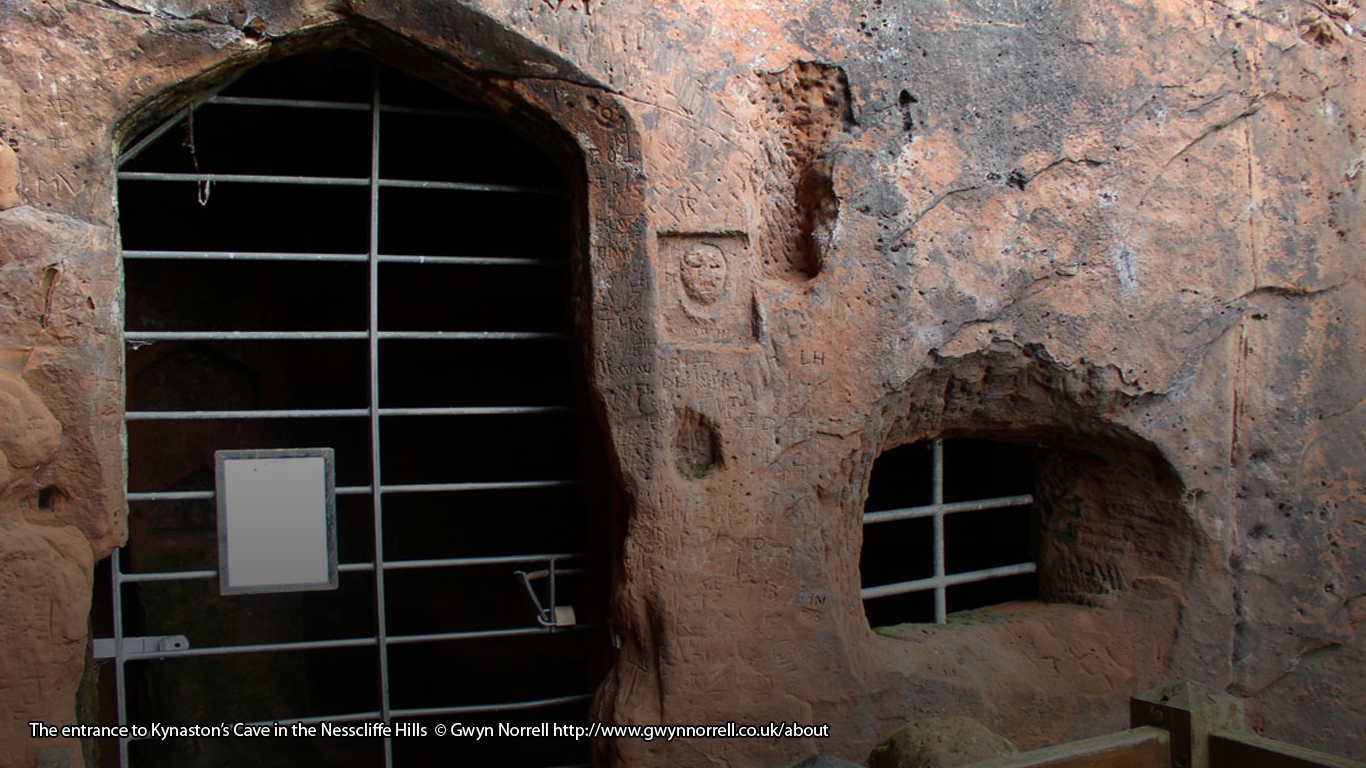

During the Dark Ages, this oak was a meeting place and served as the ‘court’ of ‘justice,’ when it became known as the ‘hanging tree.’ It is said that trials sometimes involved a race between the accused and their accuser. If the accused reached the Oak first, then they were deemed innocent, if the accuser won the race, then the accused was guilty and would be hanged from the tree. It was believed that God would intervene and make sure that the right one reached the oak first.

As is often the case with such ancient oaks that served as boundary-markers, way-markers and meeting places, the site became the local seat of power. Cadwfgan, an early Prince of Powys whose armies were instrumental in repelling the first Norman invaders, is reputed to have resided at the site which became the Nannau (pronounced ‘nan-eye’) estate. By the mid-fourteenth century, it was in the hands of Hywel Sele, supporter of King Henry IV and cousin to the famous Welsh rebel and revolutionary Owain Glyndŵr. So, in the year 1402, the stage was set for a dramatic tale of treachery and revenge to be played out at the Nannau estate.

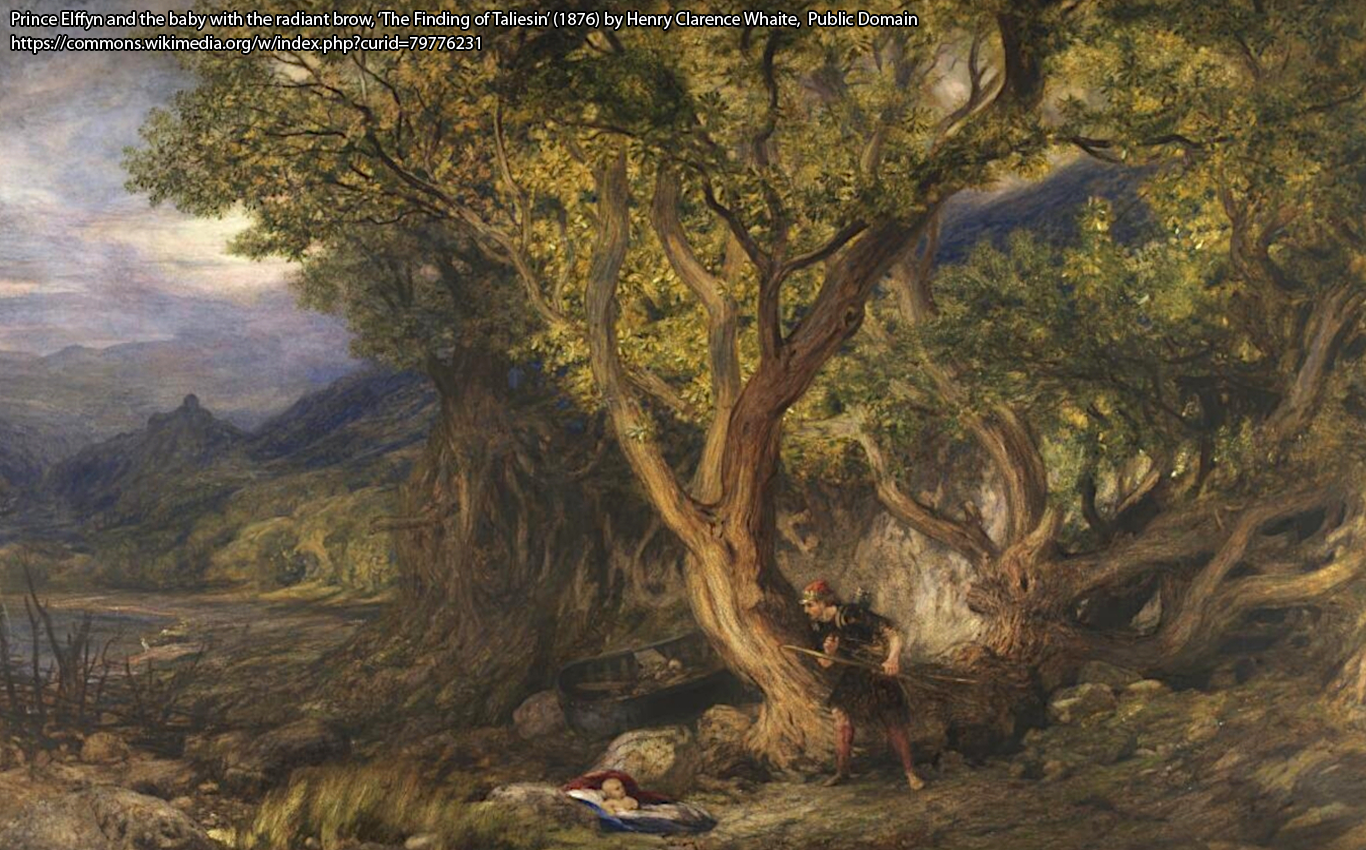

Versions of this story differ, and the motivations have changed with retellings, adapting the dominant attitudes towards the Welsh or the English. The action takes place when Owain visits Hywel to enjoy the estate’s extensive deer park and discuss political matters. Hywel invites Owain out on a hunting trip, deep into the forest, to seek a specific spotted deer. Owain, suspecting ulterior motives, wears his chainmail under his jerkin. Sure enough, as Hywel takes aim at their quarry, he turns his bow on his cousin! The arrow bounces off Owain’s metal underwear and then the men draw their swords. The fight ends with Owain dealing the fatal blow, finding himself faced with a dilemma…

Tensions between the English and Welsh are already running high, to say the least. Owain, a supporter of Welsh independence, killing his cousin who openly welcomes English rule, will spark off a war before proper preparations can be made. So, remembering a great ancient oak they had passed, Owain drags Hywel’s body there and hoists it into the hollow trunk. It is said that, to cover his tracks, he then set fire to the house so it would be presumed that Hywel failed to escape and was consumed by the flames.

Decades later – after Owain Glyndŵr has led a successful revolt against the English, establishing Welsh Parliaments before eventually being defeated at Harlech – a mysterious emissary visits the house at Nannau. He has news from Owain, who now lives out his final days in hiding. The messenger tells Hywel Sele’s widow of her husband’s true fate and leads a group of men to the ancient oak. Over the years, the tree has grown gnarled and twisted, its branches losing their bark and resembling skeletal arms, as if trying to mime its dark secret. The men split open the great bole of the oak to uncover the body stowed within, a rusting sword still clutched in its bony hands.

“And to this day the peasant still,

With cautious fear, avoids the ground;

In each wild branch a spectre sees,

And trembles at each rising sound.”

So, by the 1500s, the Great Blasted Oak at Nannau already had a dark reputation. It was generally avoided by locals, who believed that spirits haunted its twisted boughs and reported cries of terrible anguish issuing from the hollow trunk at night. As that century drew to a close, it seems that the local witchfinders were again using “The Hollow Oak, Haunt of Demons,” as their designated ‘hanging tree,’ and took to persecuting with such great gusto that, when King James passed his 1604 Witchcraft Act, it was deemed that Dolgellau needed a proper Gaol and Courthouse. When the Jailhouse was completed in 1606, the role of the tree was commemorated in decorative plasterwork.

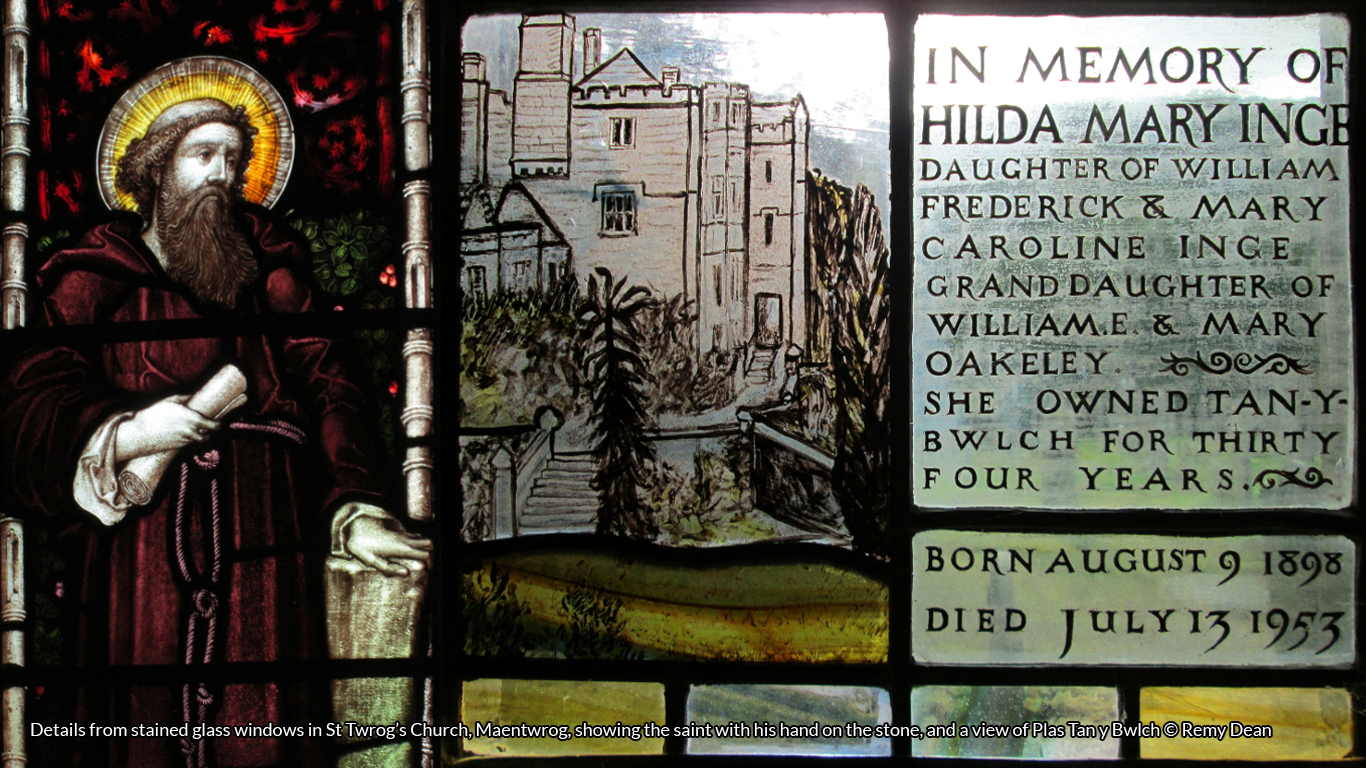

Today, the building is home to Y Sospan, a quaint coffee shop. If you venture upstairs to the function room, you will find that some of the original plasterwork is preserved, having been hidden behind cladding for much of the building’s modern history. A coat of arms featuring a lion and dragon as its bearers, dated 1606, is emblazoned above the mantelpiece. Above this, tucked away in an out of reach gable-end, is an altogether more sinister and disturbing image.

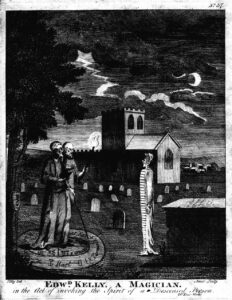

The plaster’s frieze is centred by a great tree. The body of a convicted witch hangs from a lower bough and, beneath, an accused woman is being ‘tried’ on a ducking stool. The figures are huge-headed and grotesque in the medieval style. On the other side of the tree, is a scene of a church and graveyard in which a robed figure, seemingly knelt in a magic circle, appears to be practicing necromancy, summoning another hooded figure to rise from a tomb. This scene is in a more sensitive style, with correct proportions and perspectives, and probably replaced earlier imagery that had fallen away.There is a clear similarity, in both layout and subject, to an 1806 engraving of Edward Kelley, and an associate, “in the act of invoking the spirit of a deceased person,” found in the book Astrology by Ebenezer Sibly. This was most probably the inspiration for the plasterwork picture and leads some to speculate that the entire frieze may be a Regency, perhaps even Victorian, folly.

Closer inspection of this intriguing frieze reveals strange details in the central motif of the tree. There is an owl, some sort of squirrel-goat, a Tudor rose, and prominently presiding over all is the bat-winged figure of the Devil, with horns, clawed hands, cloven hooves, and his second face grinning from his groin.

The plasterwork is obviously very old and presumed to be original, though its provenance is not fully verified, so this heady mix of motifs raises more questions than answers. Perhaps the most interesting detail to note is that the boughs of the tree are not moulded from the plaster, but seem to be real branches, set into the plaster plane. Some say this is a form of reliquary and the branches were taken from Derwen Ceubren yr Ellyll itself, to record its role in the witch trials. If this is the case, it would not be the only surviving remnant of the great Oak…

In 1813, Sir Richard Colt Hoare, the renowned horticulturist of Stourhead, was visiting his friend and fellow Baronet, Sir Robert Vaughan, at his home at Nannau. Hoare had a particular interest in ancient trees and so chose to draw the (in)famous Derwen Ceubren yr Ellyll, on “one of the most sultry days ever felt.” The girth of the oak had been recorded as nearly 28 feet, indicating that it was around 900 years old at the time. It turned out to be fortuitous that Hoare drew the tree, for a great thunder storm that had been brewing on that “most sultry” day in July broke during night. The very next morning, the “ancient and venerable oak” was found felled by lightning and scattered by the storm.

Sir Vaughn ordered the wood to be collected and had several items made from it, including a set of turned stirrup cups to be used at celebration dinners. It is said that those who drank from the cups were plagued by ghostly apparitions and suffered nightmares for several nights afterwards. At least four of these cups were sold at auction by Tamlyn & Son of Bridgwater in 2008, and one of the silver-rimmed, acorn-shaped vessels is now displayed in the National Museum in Cardiff. The wood was also used to make furniture and picture frames; one used for an etching made from Hoare’s fateful drawing. This item was sold by Bonhams auctioneers in 2014 as part of a lot to accompany “a Victorian figured oak breakfast table, Welsh, the timber reputedly from an oak tree known as Derwen Ceubren yr Ellyll.”

The folktales of the tree have inspired writings by Rev George Warrington (1744 – 1830) – quotes from his poem ‘The Spirit’s Blasted Tree’ punctuate this article; Elliott O’Donnell – who based his 1924 short story ‘The Strangling Oak of Nannau Woods’ on the Demon Oak; and its darkly rich history was the seed (perhaps I should say ‘acorn’) for my own 2008 tale of the supernatural, ‘Final Bough.’

On this zoomable map surveyed in 1887, a cross shows where a sundial had been placed, marking the “Site of Ceubren yr Ellyll.”

Do check out Final Bough by Remy Dean!

‘An internationally renowned sculptor accepts a commission that will take him back to his childhood homeland, where deeply rooted fears and half-forgotten memories threaten to surface once more… The Tufflin Oak had stood like a sentinel of the valley for centuries until recently felled by a freak lightning strike.

What was it about the ancient tree that had fascinated him as a child?

What dark family secrets still lurk in the branches of the local lord’s own family tree?

Set against the legend-rich landscape of Snowdonia and inspired by local folklore, Final Bough is a contemporary tale of the supernatural, with a traditional twist – from the author of Scraps.’