A lot of folklore is concerned with other realms. Worlds that exist apart, yet overlap or interact to varying degrees. It is this aspect that aligns many features of myth, folklore and religion around the terrestrial realm we all share… and the idea of the Three Realms has been repeatedly explored through stories, art, psychology, and now the existence of separate realities is widespread in scientific thought. Why does the belief in the Three Realms persist so prominently across multiple cultures spread far and wide, geographically and historically?

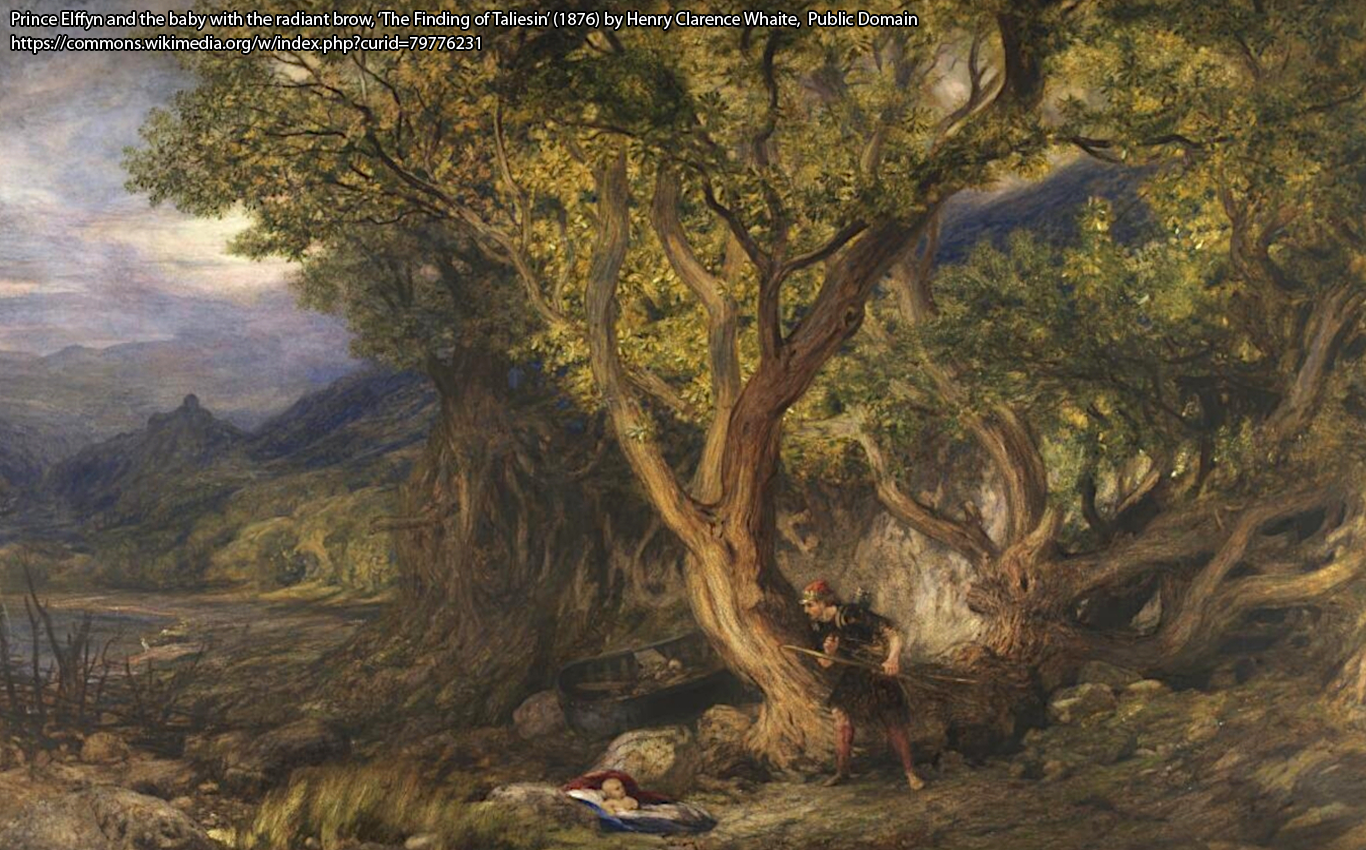

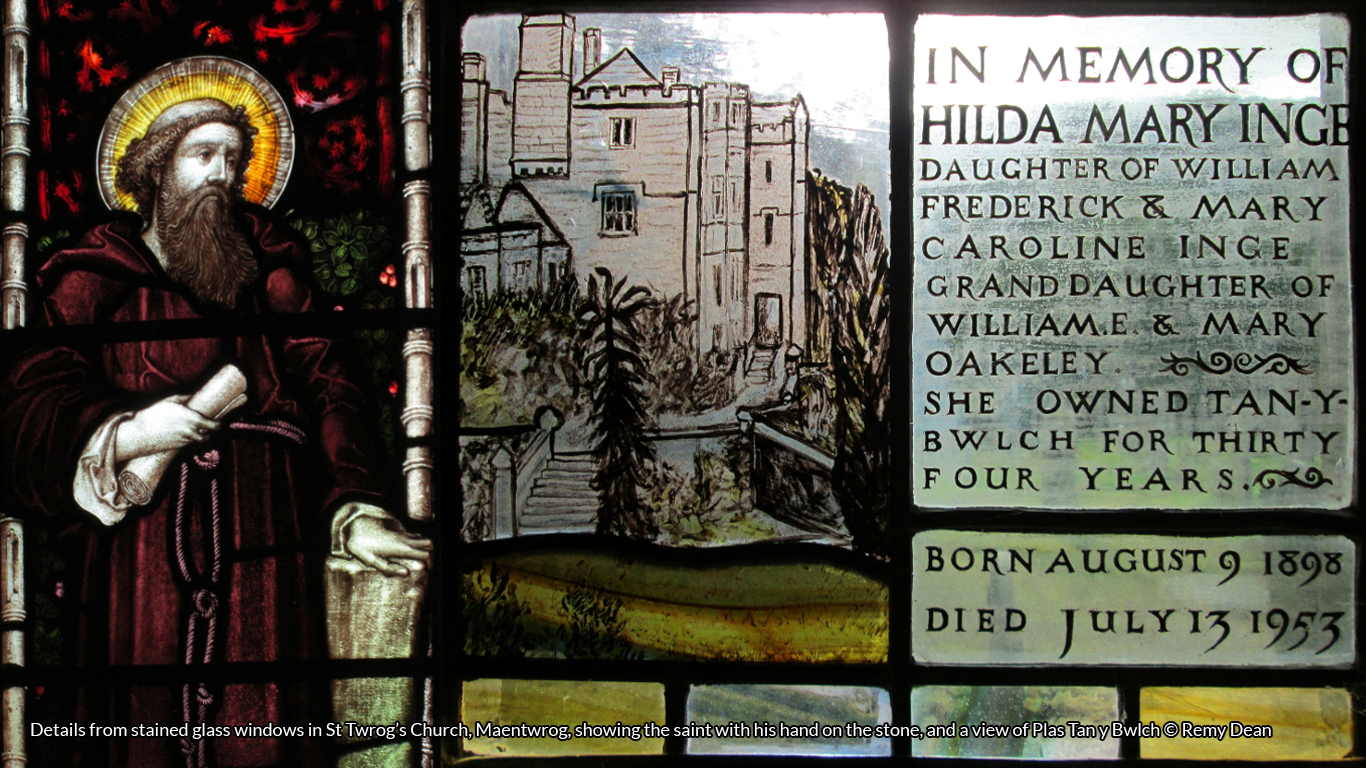

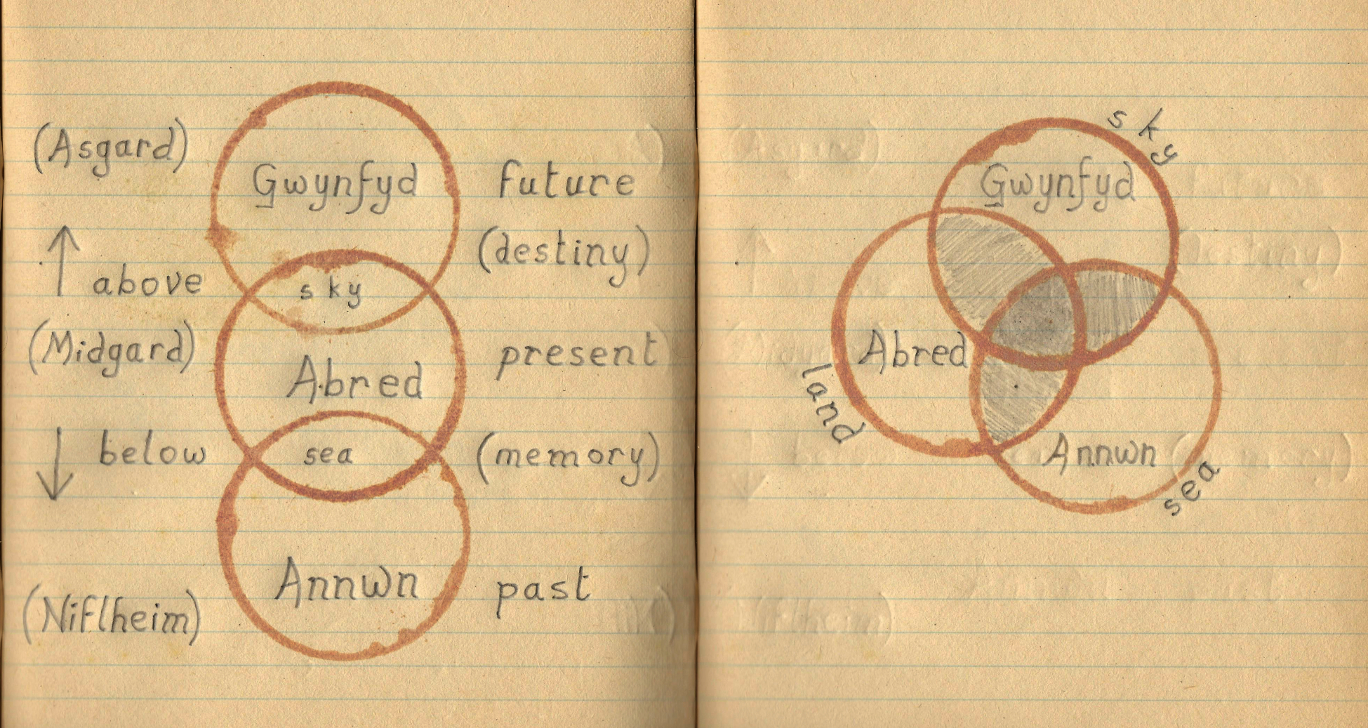

The motif of three worlds is transcultural, and a comprehensive catalogue is impossible here. For me, the closest to home, geographically at least, is the cosmology of the Celtic-revival and Druidry in which we find the three realms of Annwn, Abred and Gwynfyd. Some of these ideas derive from ancient tales collected in the Mabinogion, though they have since been confused and compounded by later stories, such as those collected in the Barddass manuscripts published in 1862.

The Fair Ones reside in the realm of Annwn, sometimes these are spoken of as if they are also the immortal spirits of the ancestors. Their king, Arawn, is one of the most feared, and respected, figures in the Mabinogion. In later tales, more associated with the Arthurian cycle, Arawn is confused with Gwyn ap Nudd, King of Tylwyth Teg (the Welsh Fairy Folk), and as master of the eternal Wild Hunt, leads a pack of spectral hounds, the Cŵn Annwn, across the night sky.

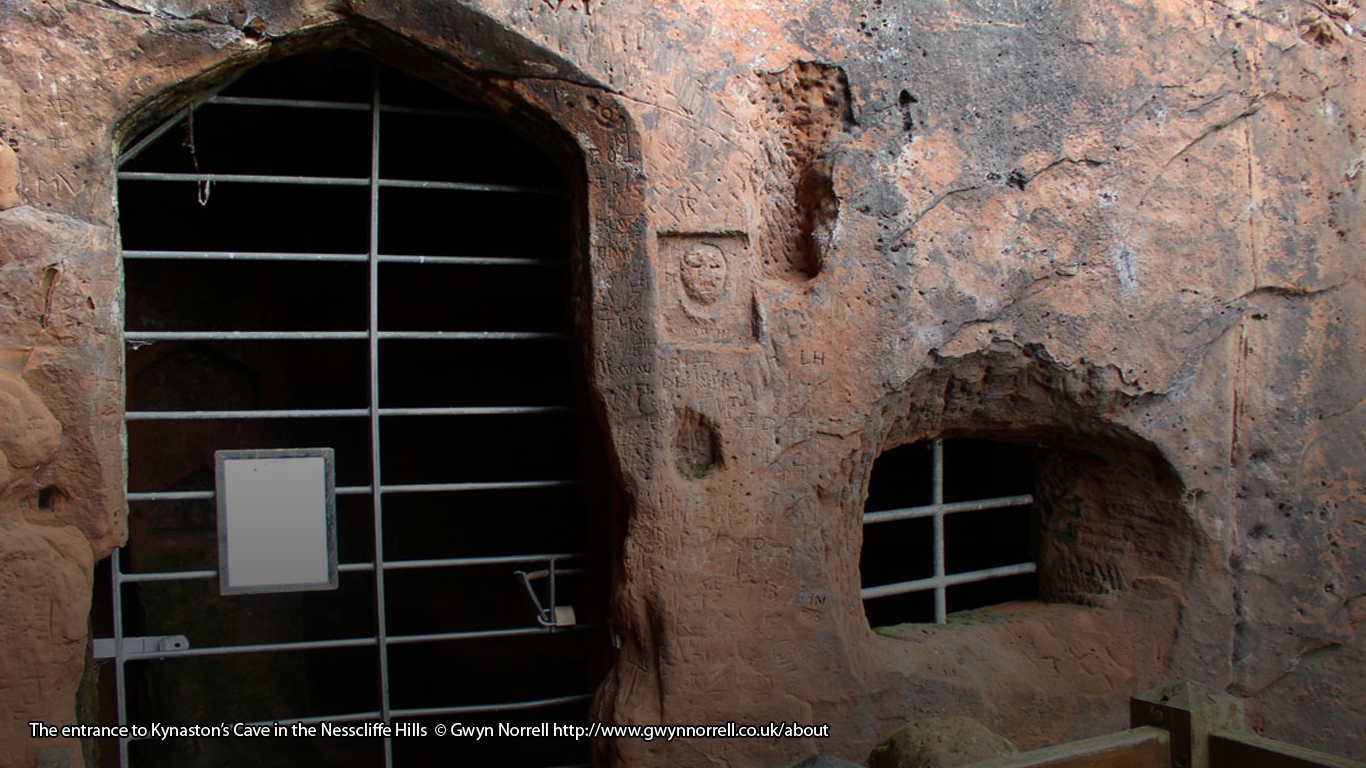

Annwn is the underworld where the afterlife is unblemished by earthly burdens such as disease, hunger and old age. It represents the past, and is associated with lakes, rivers and the sea. Mortals could enter Annwn via underground lakes in deep caves. Access could also be gained through the low mists that appear to lift the tops of hills, or to separate a lake from its shore, to create gaps through the land. A few mortals have entered on the personal invitation of Arawn, who often rode abroad through Abred to guide the dead.

Abred is the realm we usually see around us. It is rock, tree, stream and breeze. A physical realm of land, which our bodies are a part of. It represents the present, the moment we live in, as it moves through the cycle of the seasons. It exists between Annwn and Gwynfyd.

Gwynfyd is a realm of eternal spirits, associated with the sky and the heavenly bodies that move across it. It is also synonymous with destiny. It is much less accessible than Annwn, though some of the spirits interact with us, and can bring drought or flood, disaster or good fortune. The three realms also intertwine and overlay each other. The sky can be seen on the surface of lakes, often touches the land as fog, and the flow of water links all three realms.

In modern Druidry, these three realms have also been associated with the transmutation of the soul and bear parallels throughout other cultures: Christian ideas of earth, Heaven and Hell, the Qabalistic three-pillars, and trifold motifs such as the triskelion – the triple spiral found throughout ancient Greek and Celtic symbolism, and the interlocking Viking Valknut.

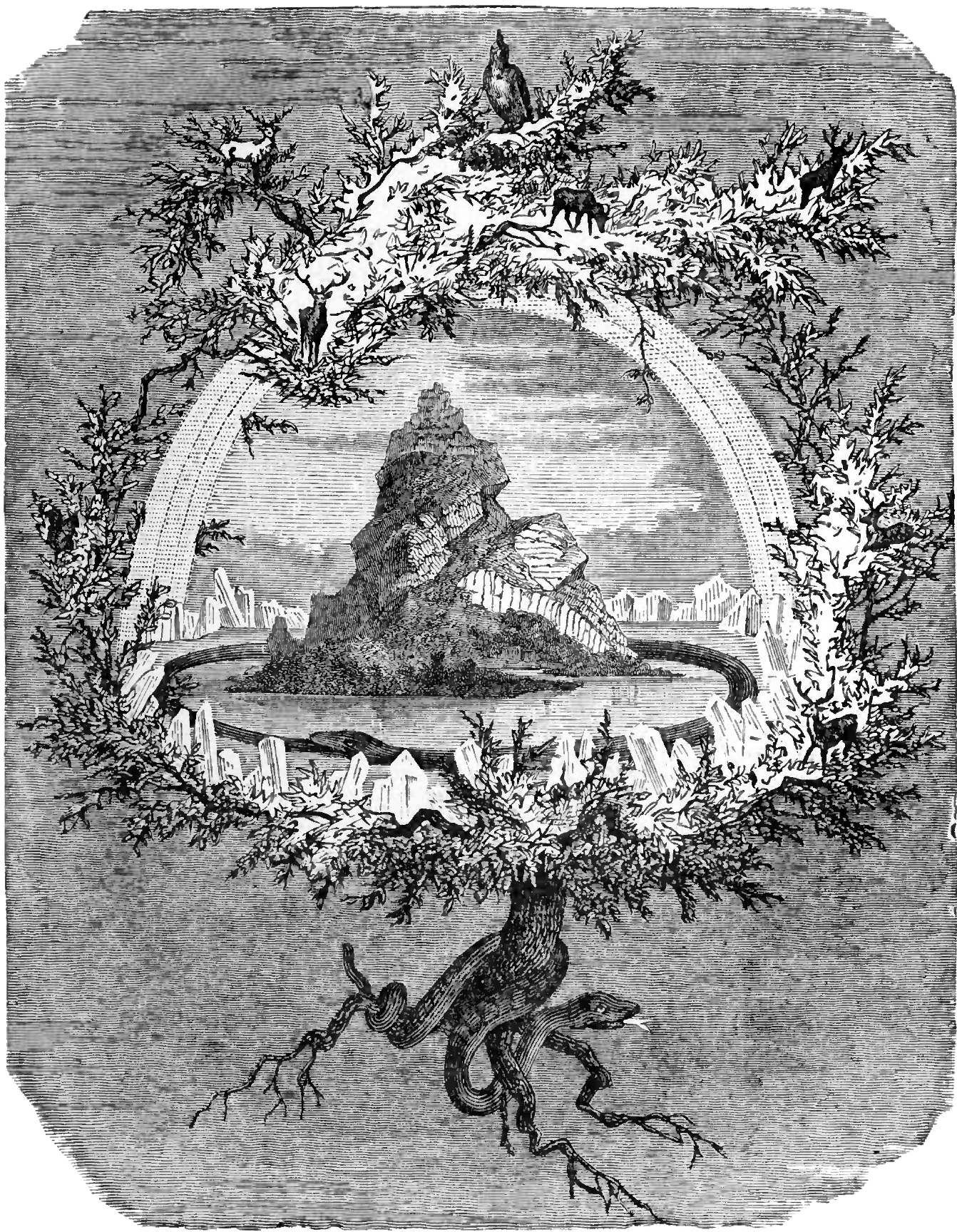

Which reminds me that the cosmology of the Viking peoples also consisted of three realms, though these were each sub-divided to make a set of nine realms, nine being three times three, and a significant number in magical symbolism. The three Norse realms of Niflheim, Midgard and Asgard were represented as features of a cosmic ash tree, the Yggdrasil.

Hel was the goddess queen of Niflheim. She was the inspiration behind Hans Christian Andersen’s Snow Queen and where the name for the infernal underworld originates. It was the dark and icy realm of the dead, the past, associated with the roots of the tree.

Midgard is the land of the living folk we find ourselves in, and is associated with the lower branches of the world tree. The realm also includes the lands of Nidavellir, where the dwarfs dwell, Svartalfheim, home to the ‘dark elves’, and Jotunheim, land of the giants.

In the highest branches, associated with the heavens, the future, the powers of light, is Asgard – home to the god-races of Aesir and Vanir, though the Vanir are often said to dwell in a region named Vanaheim. Asgard incorporates, Alfheim – home of the ‘light elves’, and is also where the brave battle-slain feast in Odin’s great Hall of Valhalla.

There is no definitive ‘map’ of the Yggdrasil and its realms because the Norse Poetic Edda are rather vague on such details. It all sounds a bit Lord of the Rings or Narnia, and that should come as no surprise as both J. R. R. Tolkien and C. S. Lewis based their mythologies on those of the ancient Norse, as did George R. R. Martin for Game of Thrones. Clearly, as with most surviving folklore, these stories still appeal today and retain a deep resonance. The Freudian branch of psychology may have chosen the Greek myths as a model for the structures of our subconscious, but the Norse sagas are easily as complex and could have served this purpose just as well.

A recurring theme of many shamanic cosmologies is that land, sea and sky embody the Three Realms. The land is our realm. The sea is often the realm, or a gateway to the realm, of the ‘others’ – ancestors or the magical ‘fairy’ folk. Usually, the sky is the home of great spirits or gods. The indistinct places where these realms meet are places of magic and revelations. On the horizon and the shoreline one thing becomes another and therefore signify transformation. In much the same way as the two distinct realms of day and night are parted by the third realm of twilight, at dawn and dusk. Overlaps ‘between the realms’ become highly significant.

Apparently, when the Indigenous Australians witnessed the arrival of explores from Europe, they presumed them to be their ancestors returning from the Realm of the afterlife. They were drained of colour and came to them from the horizon. They had never seen such ships and, in their perception, took them to be clouds – the sails being large billowing white structures that travelled a course driven by the wind.

Indigenous Australians cosmology shares the Three Realm model. The sky is where the great spirits live, and the land is but a shadow, or reflection, of the sky world. Many structures in the sky, are perceived in the land – paths and water courses are seen in the line of stars and the flow of the milky way. In their belief system the realm of the stars is more real than the shadow it casts. Likewise, our Dreaming is real life, whilst our waking life is a lesser ‘echo’ of it.

This leads us nicely to a discussion of how a concept of the Three Realms may have developed as an extension of our evolving consciousness. To operate as social animals, we need to be conscious. By conscious, in this context, I mean an ability to observe one’s own awareness from a point of view within the ‘self’. For one to cooperate with others, there first must be a concept of self and then an understanding of the other. By being consciously aware of one’s own reasoning and reactions, we can develop empathic understanding of how others may feel and respond. This immediately presents us with the self and the other.

We can observe our awareness from a structure within that some psychologists identify as the ego. Something strange soon becomes apparent: when we observe our waking awareness, it seems to be very similar to our dreaming awareness, but obeys dramatically different rules. We have two observable realms of reality. Waking and dreaming, and we exist in a third place from which we can observe both… the Three Realms within.

Once we have self-sense, then we may wonder where that came from and where is it going? Where were we before we were born… and into what realm do we go after death? To a primitive consciousness, the point of another’s death must be a source of profound consternation. Our friend is one moment talking, sharing memories of adventures in this realm, telling us of the journeys that they have been on in the realm of dreams and then, maybe only seconds later – no response.

They look pretty much the same. They are physically still there in front of us, yet they are no longer whole. Something is certainly, yet subtly, different. It is as if they crossed into the realm of dreams, permanently. From one world to the next. Therefore, the concept of an afterlife, where ancestors continue to dwell, is compelling. So, we have three realms that seem to exist, quite obviously, if we believe the observation of our own awareness. There is us awake and learning, there is the realm of dreams, weird and magical, and there is the afterlife. It is very easy to understand how this belief could develop. Once the existence of these realms is widely accepted within a social group, they then lend themselves to manipulation by cultural dogma. (The widespread, trinities, triads and the significance of the number three have already been discussed in previous posts here.)

Another set of three realms that reveal themselves soon after the development of consciousness are past, present and future. The present is the point of view within, from where we can observe our awareness. The past exists, but can only be understood from the present, and can only be visited in memory, dream or spirit form. Then, the future must also exist, but is even more elusive, though it may seem that we visit it in dreams. Again, we have three realms that, though separate, do overlap and remain interdependent.

Perhaps the motif of the Three Realms endures because of its fundamental, evolutionary basis. The internal viewpoint of the conscious self, our observed awareness, and the unconscious self, mediated through dreams. The Three Realms exist in us and so we see them reflected back in our ideas of reality, and in the stories we use to make sense of that. Navigating these realms is an ongoing quest for humanity, especially when it is sometimes unclear which realm we may be in. After all, when we are in the realm of dreams, we feel the dream is real, for as long as it lasts. Perhaps the same can be said of life…

I am currently exploring many of these concepts in my own epic fairytale fantasy, This, That and the Other. It is, of course, a trilogy spanning the Three Realms, inspired by local folklore and deserves a mention here, just so it appears in an article that also references Lord of the Rings, Narnia and Game of Thrones! This (book one of This, That and the Other) is already available as a part-work and a new, illustrated edition is available from The Red Sparrow Press, this Yuletide…

Win a copy of This by Remy Dean with Zel Cariad, with signed, limited edition illustrations!

We have two signed copies of the illustrated edition of This, by Remy Dean with Zel Cariad, each accompanied by a signed limited edition set of four illustrations, as art prints suitable for framing, for two lucky #FolkloreThursday newsletter subscribers this month!

‘They say, “What you don’t know can’t hurt you,” right? Well, of course that’s not really true. They also say, “Knowledge is power.” Well that’s not always true either… because, somewhere between not knowing and knowing, there lies imagination. That’s the key… the key that unlocks secrets.

It did, once upon a time, and it still does today…

It began a long time ago, but for Rietta, it really began when she met Carla, another very special and extraordinary person, and realised that they shared the same dreams. Or perhaps it all started when Rietta and Carla found the severely injured dog in the woods, becoming firm friends as they tried to nurse it back to health and happiness. Then there was the ‘thing’ that they glimpsed watching them from the shadows, and the mystery of the missing standing-stone… but when they find the key to another realm, well, then things really start happening!

‘This That and the Other’ is imaginative fantasy, on an epic scale. The story follows the special friendship between two girls who embark on a magical adventure together, across the three realms. It is a modern fable inspired by Welsh fairy tales and folklore, in the tradition of ‘The Neverending Story’, ‘The Box of Delights’, ‘The Chronicles of Narnia’…’

Sign up for the #FolkloreThursday newsletter to enter (valid November 2017; UK & ROI only).

The book can be purchased here.

References and Further Reading

Thomas Crofton Croker, 1828, Fairy Legends and Traditions of the South of Ireland, The Elves in Ireland, The Elves in Scotland, On the nature of the Elves, The Mabinogion and Fairy Legends of Wales

Williams ab Ithel, 1862 and 1874, Barddas: A Collection of Original Documents, Illustrative of the Theology Wisdom, and Usages of the Bardo-Druidic Systems of the Isle of Britain, Weiser Books (2004 edition) ISBN 978-1578633074

Henry Adams Bellows (translator), 1936, The Poetic Edda, via Sacred Texts on-line

Carl Jung, 1964, Man and His Symbols, Picador (1978 edition) ISBN 9780330253215

Joseph Campbell, 1988, The Power of Myth, Doubleday ISBN 9780385247733

Ellen Evert Hopman, 2012, Two Seasons, Three Worlds, Four Treasures, Five Directions: the Pillars of Celtic Cosmology and Celtic Reconstructionist Druidism, Order of Bards Ovates and Druids, http://www.druidry.org/druid-way/other-paths/druidry-dharma/two-seasons-three-worlds-four-treasures-five-directions-pillars

Luke Esatwood, 2012, The Druid’s Primer, John Hunt Publishing, ISBN 9781846947650