Huw Llwyd has been immortalised in the folklore and fairy tales of Wales, his fantastic exploits told and re-told down the ages, so many times perhaps that people have forgotten that he was, indeed, a real person: a mercenary, magician, bardic poet and bona fide ‘man of mystery’ – the genuine ‘Welsh Wizard’. Born during the first decade of Elizabeth I’s reign, he lived through the entire reign of King James (VI of Scotland, then I of England), and into the reign of Charles I, though did not live to see the upheaval of the English Civil War … or did he?

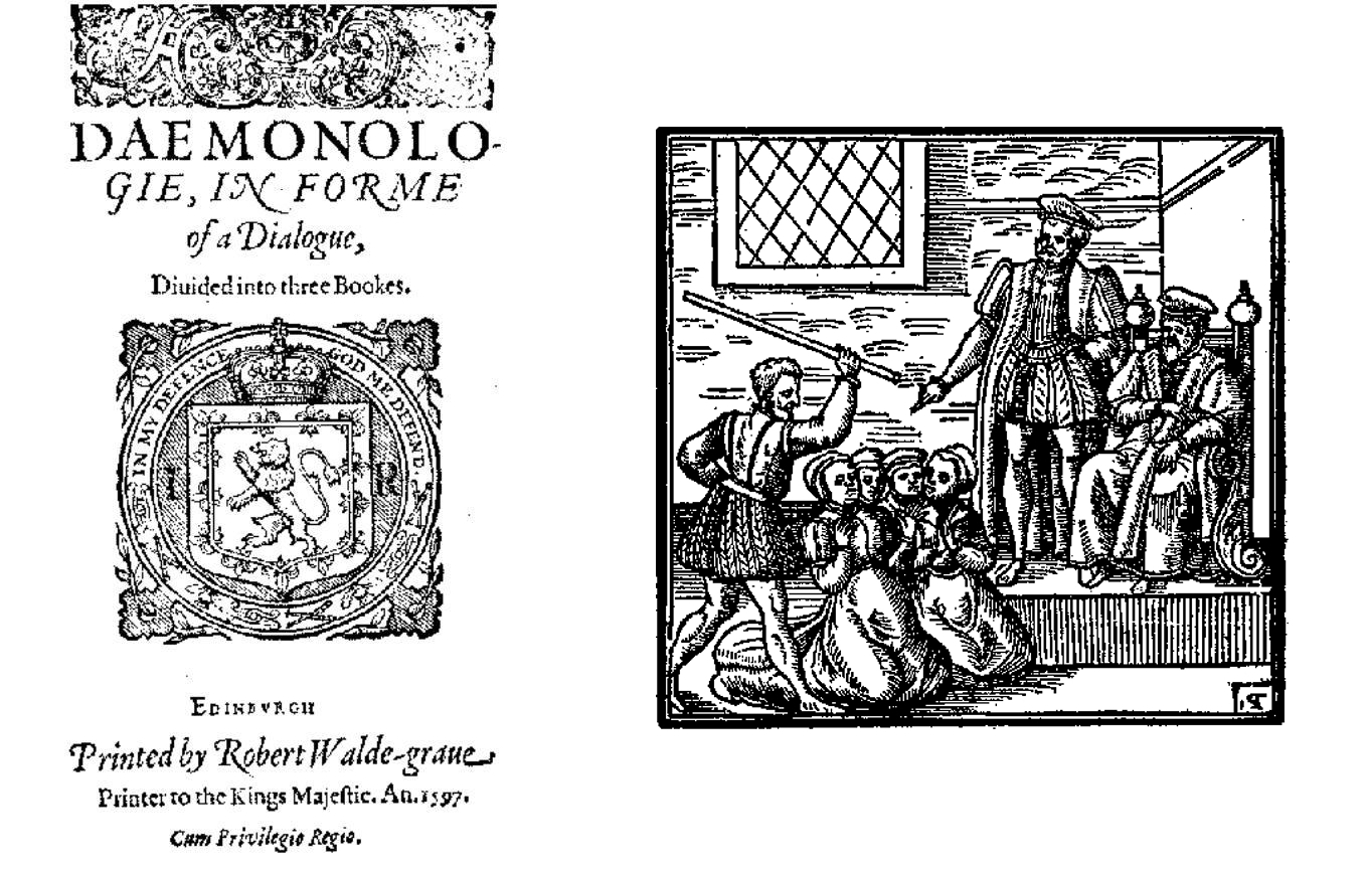

During the reign of King James, alchemy, magic, sorcery and the conjuring of spirits became closely associated with witchcraft. James adopted the ‘Christian Theory of Witchcraft’, which proposed that witches cannot act alone and must be taught by others. This meant that if one witch be found, then there must be other co-conspirators in the vicinity to be routed out. King James was paranoid that witchcraft was being used in attempts to assassinate him and studied the subject in detail. He wrote the extensive volume, Daemononlogie, in 1597, and passed the 1604 Witchcraft Act. Later, in 1611, he oversaw the translation, into English, of the Bible as the Authorised King James Version.

Surely, in this cultural climate it must have been risky to openly practice sorcery and the magical arts. It appears that Huw Llwyd, a self-styled preacher who associated with respected clerics, convinced the authorities that sorcerers were invaluable in the battle against ‘the evils of witchcraft’. If illness, misfortune and madness be attributed to demons and spirits raised by witches, then it followed that sorcerers would be needed to control and dispatch those spirits. He proceeded to do so, in style.

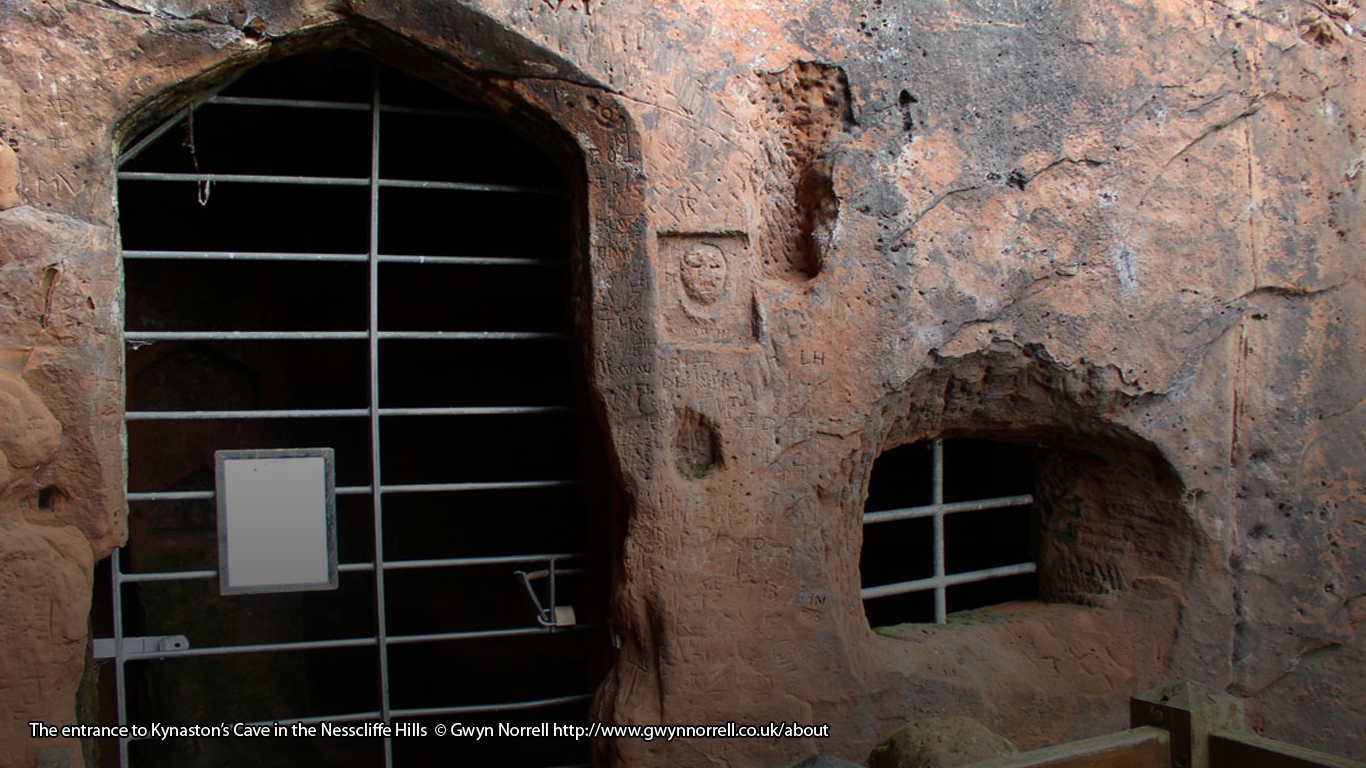

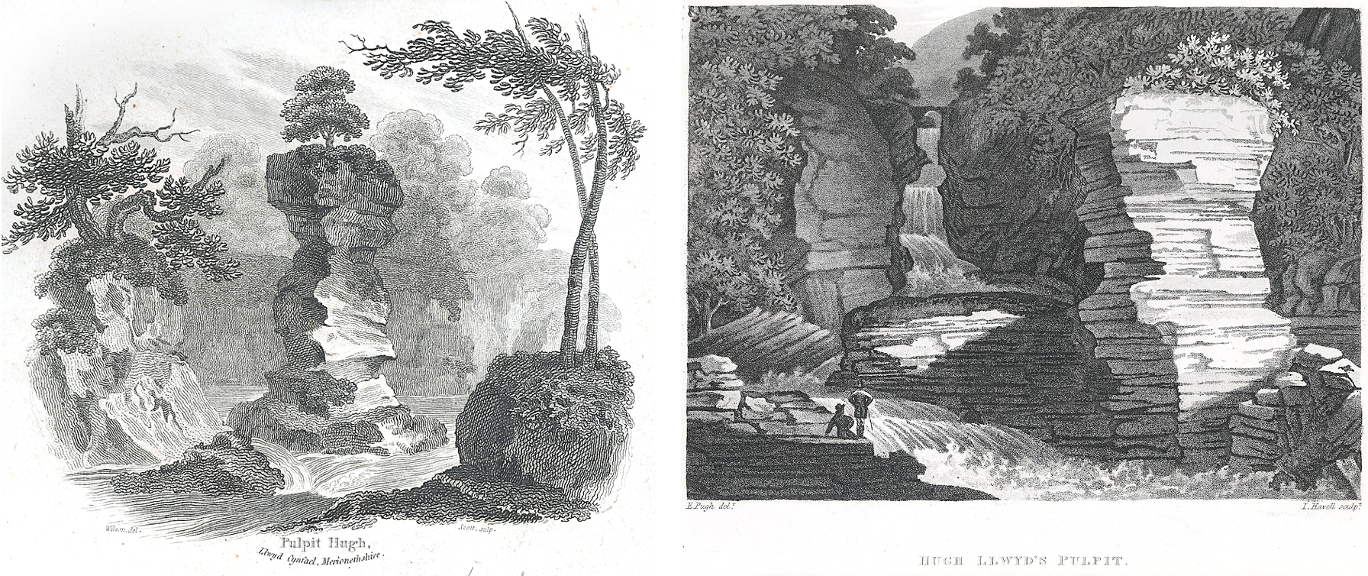

In the mountains around Blaenau Ffestiniog, where the waters of Afon Cynfal pass through a steep-sided gorge above a fierce cataract, stands a natural pillar of stone known to this day as Huw Llwyd’s Pulpit. His congregation would gather in this gorge and he would appear on the flat top of the column to preach. His sermons were dramatic and, miraculously, could be heard over the thunder of white water. This was also the place where he is said to have cast out demons.

It seems that he had studied early forms of hypnotism during his extensive travels abroad and, in a combination of therapeutic theatre, baptism and psychology, performed ‘exorcisms’. He would appear out of the mist, a formidable figure dressed in robes adorned with magical symbols and use fearsome spells to drive out the demons afflicting his patients. Huw reputedly treated patients who had travelled from as far away as France. The demons fled their victims in the form of black shadows, were caught up in the fast-flowing river and dashed apart in the torrential waterfall below. The waterfall is still known as Rhaeadr Ddu, the Black Falls.

To help visualise this, here is a description of a traditional Welsh sorcerer written by historian, T W Hancock in 1875:

“Whenever he assumed to practise the black art, he put on a most grotesque dress, a cap of sheepskin with a high crown, bearing a plume of pigeons’ feathers, and a coat of unusual pattern, with broad hems, and covered with talismanic characters. In his hand, he had a whip, the thong of which was made of the skin of an eel, and the handle of bone.”

Already an acclaimed bard and harpist, Huw was soon recognised as the region’s go-to person to deal with anything weird and witchy. He was called upon to investigate inexplicable occurrences and unsolved crimes, as well as suspected witchcraft. It seems that he was regarded as the ‘Sherlock Mulder’, or should that be the ‘Fox Holmes’, of North Wales in the Age of Discovery.

Huw was a seventh son and ate the flesh of eagles to bestow magical powers on himself and his descendants for nine generations …

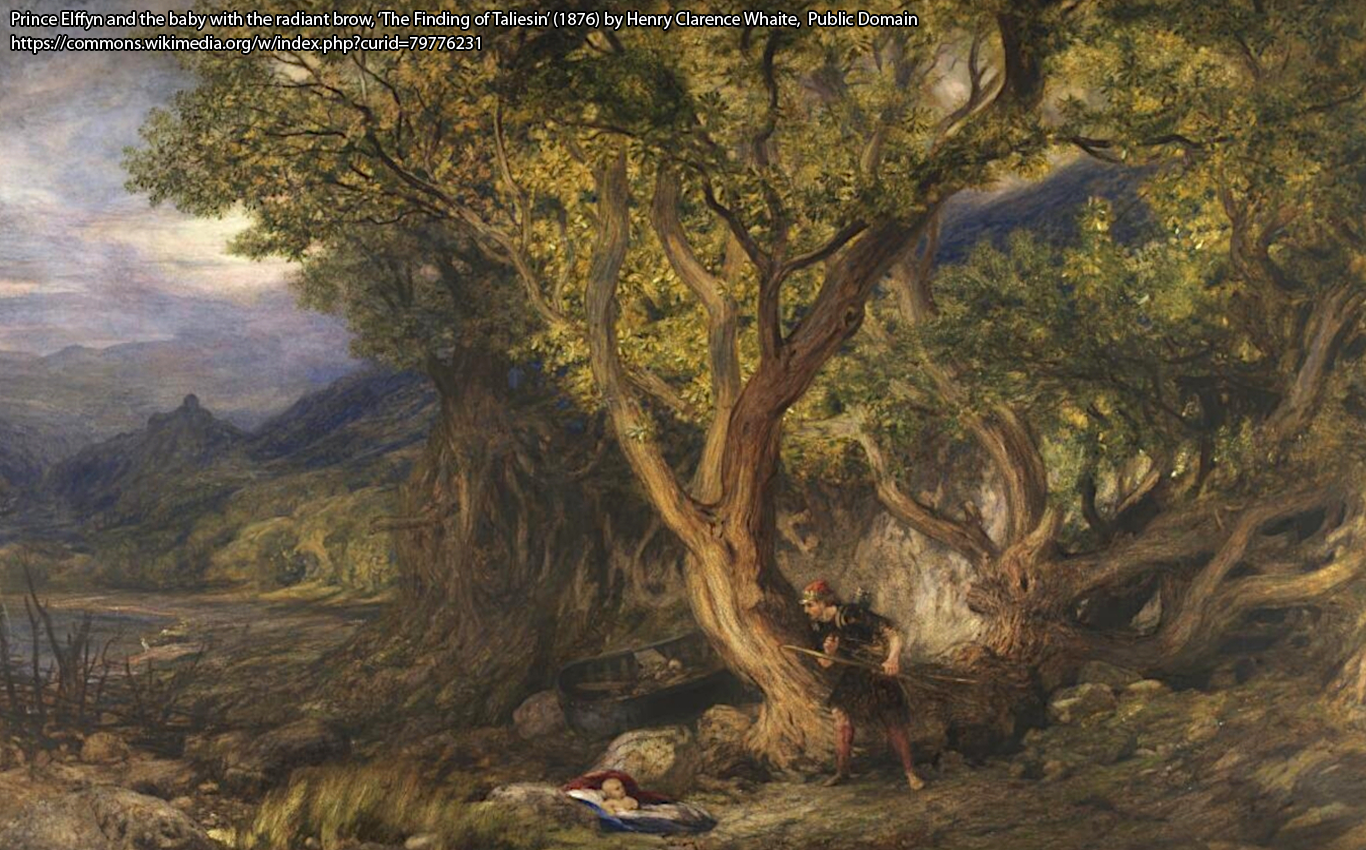

William Jenkyn Thomas includes three stories of Huw Llwyd in his classic 1908 collection of folk tales, The Welsh Fairy Book. He tells us that Huw was a seventh son and ate the flesh of eagles to bestow magical powers on himself and his descendants for nine generations …

In one tale, Huw solves a case of serial theft perpetrated by two inn-keeping sisters, who were also witches and could transform into cats at night to stealthily pore – or rather paw – over the belongings of their guests to steal anything of value. He sleeps with his magic sword at his side and when the cats sneak down the chimney into his room, strikes one a blow. The next morning, one of the sisters has a bandaged hand. Instead of reporting them to a witch-finder for trial, he assures the sisters that the inn is now under his protection and there will be no more stealing. This claim is proven true, for without the reputation of a dangerous place, the inn thrives and the sisters earn a good, honest living from then on.

(Public Domain images)

In another story, he mesmerises a gang of bandits, who had followed him to a tavern, by causing the table they are sitting at to extrude antlers that they are unable to look away from, until the following morning when the sheriff comes to arrest them. A third features a conjuror who revenges himself upon an unscrupulous and extortionate inn-keeper by leaving behind a spell that makes everyone in the room relentlessly dance and sing until all are close to terminal exhaustion. He later sends instructions of how to find the spell and fling it into the fire, thus lifting the curse. These three tales imply that he was just, effective and had a sense of humour.

In other less well-known stories, the young Huw collects a barn-full of crows, reveals a much darker side during a magical contest with a rival sorcerer, and inadvertently introduces the devil to tobacco and gunpowder…

The real Huw Llywd certainly lived through exciting times of international intrigue, political upheavals and saw the dawn of a new age of science and knowledge. Notable contemporaries include Tycho Brahe, the Danish brass-nosed astronomer; William Shakespeare, the great bard; and Dr John Dee, advisor and astrologer to Queen Elizabeth I, scholar, international spy, leader of a Rosicrucian Renaissance, and fellow sorcerer.

Sometimes anglicised as ‘Hugh Lloyd’, and also referred to as Huw Llwyd o Gynfal, or Huw Cynfael, there is historical evidence that Huw Llwyd was a soldier, preacher, physician, an accomplished bard, and was consulted as a sorcerer. There are references to his military service, 1585-90, under Sir Roger Williams in France and Holland. He is also presumed to have performed the duties of Chaplain and Doctor for those wounded on the battlefield as he shared some medical training with his brother, Owen Llwyd, who was a qualified physician. There is also mention of his service in Belgium and Germany.

The priest and bardic scholar, Ellis Wynne (1671 – 1734), acknowledges the books of Huw Llwyd as a source for his own work, The Book of Ancient Remedies. Auction records are mentioned of the sale of Huw Llwyd’s treatise on military strategy, as consulted by Napoleon Bonaparte. His writings are noted in the Peniarth manuscripts, collected by the antiquarian and historian, Robert Vaughan (c.1592 – 1667).

on his death bed, he ordered one of his daughters to throw all his books on the ‘black arts’ into a lake – where they were received into a pair of ethereal hands

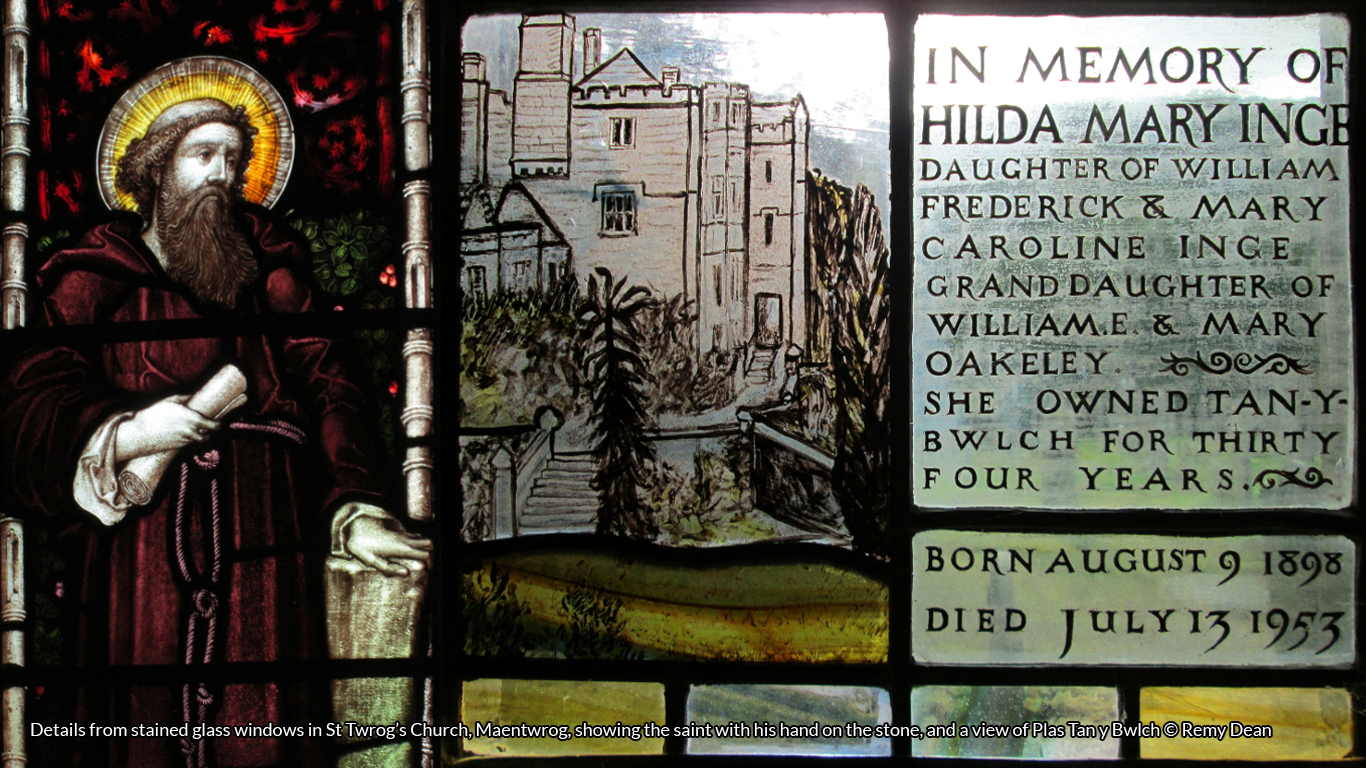

In other documents held at the National Library of Wales, Huw Llwyd is listed as purchasing greyhound ‘cubs’ in 1606, publishing verse in 1620, and still being in residence at the Maentwrog Cynfal Fawr house in 1629, where he had been neighbour to Edmwnd Prys (1544 – 1623), Archdeacon of Merioneth, Rector of St Twrog’s Church in Maentwrog, known for assisting in the first translation of the Bible into Welsh, and who was also a bardic poet.

Huw is recorded as the father of three sons and two daughters, though there are also mentions of a fourth son and third daughter, which leads us to the final mystery of Huw Llwyd: there are no records of the births nor deaths of these two ‘extra’ children. Apart from a story that, on his death bed, he ordered one of his daughters to throw all his books on the ‘black arts’ into a lake – where they were received into a pair of ethereal hands – I am unable to find any record of the death of Huw Llwyd, or his wife. There are no known portraits of Huw Llwyd. No will was ever executed or probate granted for his estate in Maentwrog. It is as if… he never died …and may yet live on.

Research for this article was undertaken during my 2016 residency at Plas Tan y Bwlch, Maentwrog, and, again, I extend big thanks to Twm Elias for generously sharing his knowledge of local history and folklore, and to Andrew Oughton for having me at the Snowdonia National Parks Study Centre and granting access to the archives. Other works generated during my residency, including visual responses, are currently on exhibition there, in the Stable Block Gallery.

Recommended books from #FolkloreThursday

References & Further Reading

Robert Vaughn, 1667, The Peniarth Manuscripts Collection, The National Library of Wales

T W Hancock, 1875, Llanrhaeadr-yn-Mochnant: its parochial history and antiquities, Montgomeryshire Collections vol. 8

W Jones, 1879, Hanes Plwyf Ffestiniog (History of Ffestiniog Parish), Ffestinfab

G J Williams, 1882, Hanes Plwyf Ffestiniog (History of Ffestiniog Parish), Hughes and Sons

Jenkyn Thomas, 1908, The Welsh Fairy Book (Illustrations by Willy Pogány), F A Stokes NY, available as Dover Publications edition: ISBN: 1537491350 and on-line here http://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/celt/wfb/

J H Davies, 1908, Gweithiau Morgan Llwyd, archived research papers at National Library of Wales

E Lewis Evans, 1930, Morgan Llwyd: Ymchwil i rai o’r prif, ddylanwadau a fu arno, H Evans Liverpool

Mrs K W Jones-Roberts, 1959, Merioneth Historical & Record Society Journal

Dr M C Bridge FSA, October 2011, Tree-ring Dating of Cynfal Fawr in Maentwrog, Oxford Dendrochronology Laboratory Report 2011/35

Merfyn Williams and Twm Elias, 2015, Plas Tan y Bwlch, Snowdonia National Park Centre, ISBN 978-1-84524-237-4

The National Library of Wales https://www.llgc.org.uk/collections/learn-more/archives/

The Discovering Old Welsh Houses and North-West Wales Dendrochronology Project

http://www.datingoldwelshhouses.co.uk/

The Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments in Wales http://rcahmw.gov.uk/home/

Plas Tan y Bwlch, the Snowdonia National Park Environmental Studies Centre http://www.eryri-npa.gov.uk/study-centre