Folktales have been told for thousands of years, probably since our ancestors began to sit around a campfire of an evening, before retiring for the night. In this article, I discuss how we know some of the reasons people told each other these stories, as well as some of the purposes behind the telling of tales.

Folklore is at heart oral and behavioural traditions, so the notion of written folklore is somewhat oxymoronic. Any attempt to preserve oral traditions in writing involves a transformation of the material to some degree. Collectors of folklore, such as the German brothers Grimm, also altered their source materials according to their literary sensibilities, and in deference to their readers. Moreover, the editors of subsequent editions of the collections of folklore have made changes to the texts as they were originally published, removing a published text even further from its oral origins. Thus considered, folklore texts may be viewed as the creations of their collectors, authors, and editors, as well as the the result of an oral tradition. The Norwegians Asbjørnsen and Moe appear to have been so aware of the conflict between oral sources and written tales that, in the introduction to the 1852 edition of their tales, they termed themselves ‘retellers’ as well as ‘collectors’.

Peter Christen Asbjørnsen learned a way of returning to a more authentic experience of the folktales from the Irish collector Thomas Crofton Croker. In his Fairy Legends and Traditions from the South of Ireland (1825), Croker has composed frame narratives, each embedding a number of shorter folktales. The purpose of these narrative frames is to illustrate the kinds of people who told the tales, and in what kind of situations they told them. Asbjørnsen’s adoption of this method gives us a cross section of the people who told his tales, and also the function of the tales in the situation they were told.

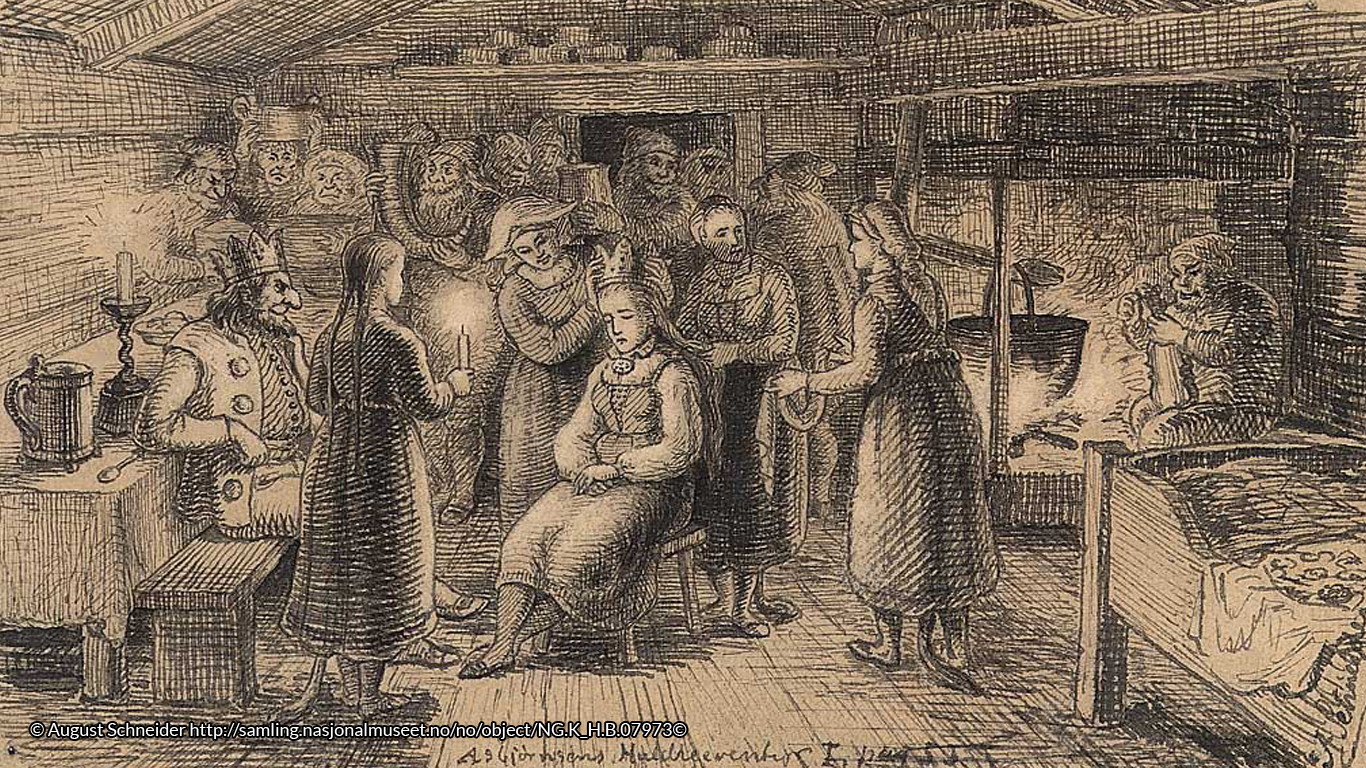

Asbjørnsen shows that folktales were told for entertainment, especially of children. In An Old-fashioned Christmas Eve (En gammeldags juleaften) a pair of old-fashioned, naive spinsters tell folktales of the nis and a church service held by the dead, as a way of entertaining their nieces before their Christmas dinner is ready. The adults are amused when the children are scared by the tales, providing entertainment for all present. In Legends from the Mill (Kvernsagn), after the narrator gets things going with a tale about the mill-growler—a subterranean creature that snags the millrace, and which has a mouth ‘so wide that his lower jaw was the doorstep and the upper jaw the lintel’—an old, grey-bearded sawmill worker with a red woollen hat tells a tale of a parson’s wife who could transform herself into a wicked black cat that leads a host of these sinister creatures. The entertainment is ruined, however, when one of his audience, a half-grown boy on his way home after running an errand for a local clerk, is frightened by the sawmill worker’s tale, which irritates the latter: ‘Aren’t you ashamed to whine like that, so big and tall as you are?’

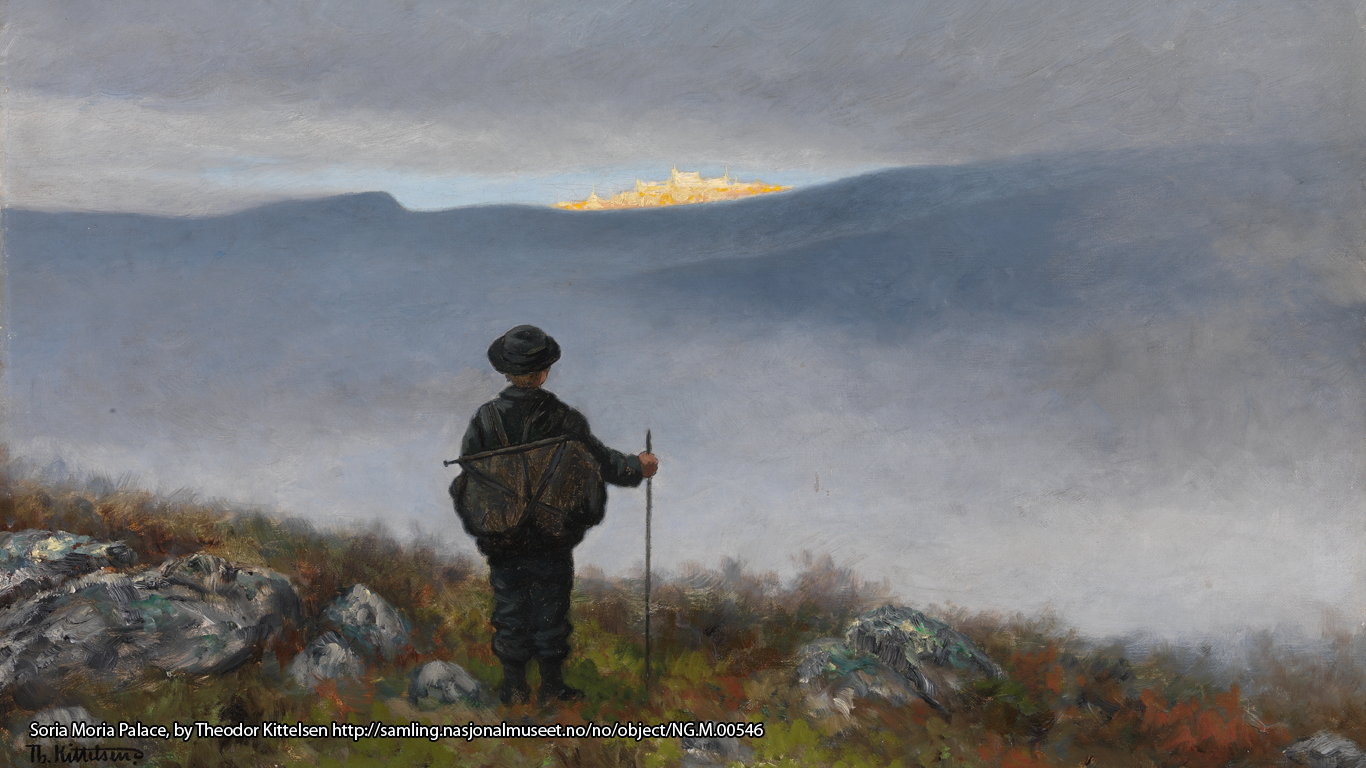

Folktales are also shown to bring comfort to those far away from home. In On the Alexandrian Height (På høyden av Aleksandria), the petty officers and ratings of The Eagle, a Norwegian corvette waiting to berth in Egypt, tell tales to offset the effects of homesickness during the Christmas season. They tell tales of the nis, both on board and on the farm; of a parson’s wife who is exposed as a witch, and condemned to burn, but who escapes by climbing to the heavens from the execution fire; and of the wedding of the subterranean King of Ekeberg—which is sabotaged by the neck*, who in the form of a horse, runs off with the bride.

Sometimes, an informant uses a folktale to explain something. In Berte Tuppenhaug’s Tales (Berte Tuppenhaugs fortellinger), for example, the ‘wise woman’ Berte attempts to heal the narrator’s injured foot by pouring brandy over it and reciting a charm. The narrator asks her how she learnt her arts, and she tells him of her uncle’s powers, and how he was weakened through encountering the hulders. Her tales continue, however, moving to how the hulders spring weddings on unsuspecting Christians. In the same way, although the narrator is not present in A Wise Woman (Ei signekjerring), the wise woman uses tales about changelings to persuade the mother who has sought her advice, that her child is rather suffering from svekk, a folkname for rickets (caused by a vitamin D deficiency). Unfortunately, the cure for the infant’s ‘svekk’ (burying items of silverware at three different locations) is just as ineffectual as the cure for a changeling (thrashing the child on a rubbish heap, three Thursdays in a row, at which time the switch will be reversed), albeit much less brutal.

Once in a while, someone tells a tale for a purpose that goes beyond entertainment, comfort, or enlightenment, however. In Hulder-kin (Huldreætt), Marie, the young daughter of a district governor, uses a tale of how her great-grandfather, or great-great-grandfather (she is not sure which) married a hulder, as a way of parrying the narrator’s clumsy romantic advance. Since she has the hulder’s ‘troll blood’ in her veins, she is no longer a good match; but she half-threatens the narrator, too: ‘You may conclude for yourself what to expect, should you seriously make me angry.’

There have, no doubt, been many reasons for people to tell each other folktales. There is comfort in them; and tellers and listeners have used them to make sense of the world around them. Some may even have used folktales to keep others at arm’s length, when necessary. The most obvious reason for telling tales, however, is the reason we still listen: they are strangely entertaining.

* The neck (Norwegian: nøkken) is a Germanic shapeshifting water spirit that especially enjoys collecting Christian souls by drowning them. Appearances as a man or a horse are the most common manifestations in Norwegian folklore.