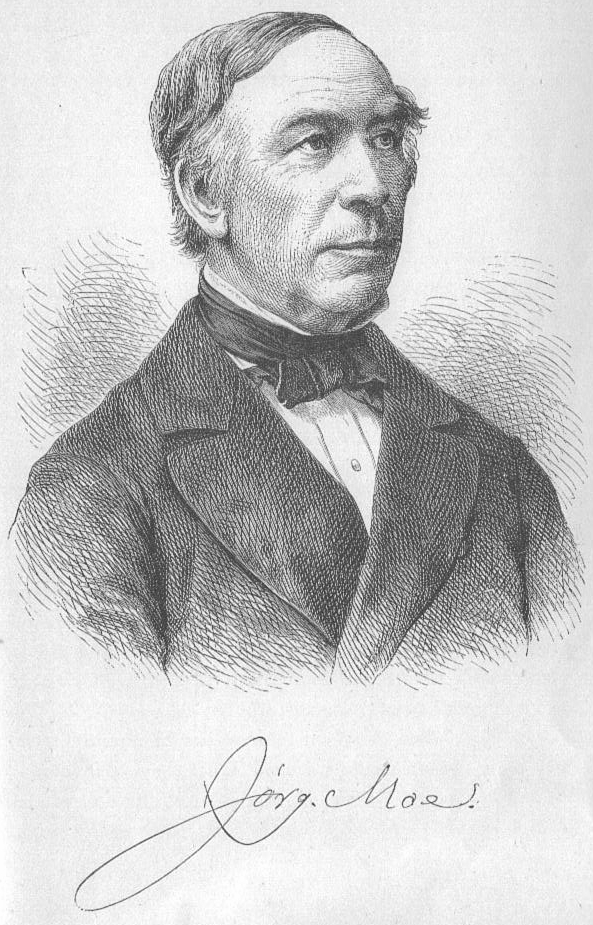

If you have heard or read the folktale “The Three Billy-goats Gruff,” you are aware of the existence of Norwegian folklore, and that it deals with trolls. Indeed, Norway is, and always has been awash with folklore. Thanks to the efforts of two men in particular, Peter Christen Asbjørnsen (1812–1885), and Jørgen Engebretsen Moe (1813–1882), we are still able to read many Norwegian tales and legends in a form that is close to the way they were told in the time before urbanisation and mass communication changed society, and thus folklore, forever.

Andreas Faye

Asbjørnsen and Moe were not the first to think of collecting Norwegian folklore; they had a predecessor—the educator and parson Andreas Faye (1802–1869). After a trip to what today is Germany, upon which he met Adam Oehlenschläger, Ludwig Tieck, Hans Chr. Andersen, Johan Chr. Dahl, and Goethe, and inspired by the Grimms’ Deutsche Sagen (1816), Faye published an edition of Norwegian legends he had collected. Norske sagn (Norwegian Legends) came out in 1833, but was a disappointment. In a review, P. A. Munch slaughtered the collection for lacking style and scientific method.[1] The book was revised and reworked, and republished as Norske Folke-Sagn (Norwegian Folk Legends) in 1844.

Despite the reputation of the material as being “as dry as tinder,” Faye’s title represents the first publication of any Norwegian folkloric material that had been collected from oral sources; he thus served as a model for subsequent Norwegian folklorists.[2]

Asbjørnsen & Moe

For present-day Norwegians, the names of Peter Christen Asbjørnsen and Jørgen Engebretsen Moe are nothing less than synonymous with Norwegian folklore. The pair met in 1826/ 1827, while they were receiving instruction at the parsonage in Norderhov, so they would be able to matriculate at the university.[3] They became life-long friends. The oral tradition concerning their time at the “student factory” in Norderhov tells that the pair were troublemakers, Asbjørnsen moreso than his younger friend, and that they sorely tested the sexton’s patience with their tricks and pranks.[4]

Each went a different way, after leaving Norderhov. Asbjørnsen went back to Christiania to study further at the Cathedral school, whilst Moe waited until 1830 before returning to Christiania. Their correspondence was rich; their letters record their dreams of literary careers. A letter to Asbjørnsen from Moe, dated January 1830, reveals too that they had at some point become foster brothers after the old Norse custom of fóstbræðralag.[5]

Asbjørnsen and Moe found different paths to their common interest in folklore, but the brothers Grimm were pivotal for both of them. Asbjørnsen borrowed Irische Elfenmärchen, Grimm’s translation of Thomas Crofton Croker’s Fairy Legends and Traditions from the South of Ireland, from the university library in 1833, the first of several times he did so.[6] And when a rumour that Faye would publish a further edition of folk legends began to circulate, a mutual friend sent him three legends that Asbjørnsen had collected, among them an early version of “The King of Ekeberg.” Faye wrote a letter of thanks, appointing Asbjørnsen “Extraordinary Legend Ambassador.”[7] In early 1835, Asbjørnsen read the Grimms’Deutsche Sagen and Kinder- und Hausmärchen, and he busied himself thereafter collecting folktales and legends from anyone who had something to tell him.

Moe’s earliest interest in folklore appears to have been as a source for writing literary tales. In a letter he sent to his sister in 1834, he writes: “do you know the tale of the Seven Foals? Refresh my memory as best you can, for I need it.”[8] In 1836, he proposed the idea of publishing literary tales in collaboration with Asbjørnsen. Asbjørnsen was neither interested nor able to take on such a rôle, he said. If, on the other hand, Moe wanted to re-tell and publish folktales in an unreworked form, then he would like to collaborate.[9] It was not before late 1836, at a time of convalescence from a two-year bout of depression, that Moe read the Grimms. He subsequently wrote to Asbjørnsen: “If ever I grow really healthy, then I want to tell tales.”[10]

In the spring of 1837, Asbjørnsen and Moe met twice, and agreed that they would do in Norway what they thought the Grimms had done: collect folklore from the common folk, and publish what they collected.[11] For the next 15 years, the foster brothers would occupy themselves collecting, editing, and publishing all the folktales and legends they could come by.[12]

Collection and Publication

After agreeing on their plan, Asbjørnsen and Moe each went on various tours to collect folklore from their local area. At Christmas 1837, the first of Asbjørnsen’s collected texts were published in Nor, a picture book for Norwegian youth. “Nor is a so-called calendar, a Norwegian variant of the German and French ‘almanacs,’ small books of fiction that were published regularly at Christmas time.”[13] The texts published included early versions of “The Boy Who Went to the North Wind and Demanded Back His Flour,” and the aforementioned “The King of Ekeberg.”

The first booklet of Norwegian folktales was published 29th December 1841 by Johan Dahl, as a favour to old friends. It was an inauspicious beginning; the cover of the small, 96-page blue–grey volume was blank—no title, no authors, no publisher. But despite its shortcomings, and championed by P. A. Munch, the same critic who had slaughtered Faye, it sold.[14]

Asbjørnsen’s and Moe’s collection tours continued, and the second half of what became the first volume came out before Christmas in 1843. The second volume was published in October 1844; Asbjørnsen’s solo project, Norwegian Hulder Tales and Folk Legends, in which he spun frame narratives around numerous short legends, after the manner of Croker, was published in two volumes in 1845 and 1848, respectively.

A second edition of Norwegian Folktales (December 1851), expanded with the tales that had been collected since the publication of the first edition, is considered Asbjørnsen’s and Moe’s masterpiece. The introduction, a meticulous 58-page affair for which Moe had received a grant from the state to write, along with 177 pages of notes, caused the publisher to request that only a few new folktales be admitted.[15] This second edition made its way to the brothers Grimm, to whom it was dedicated. Jacob Grimm wrote back to Moe, calling the Norwegian folktales “die besten Märchen, die es gibt” (“the best tales there are”).[16] More editions followed, both of Norwegian Folktales and Norwegian Hulder Tales and Folk Legends.

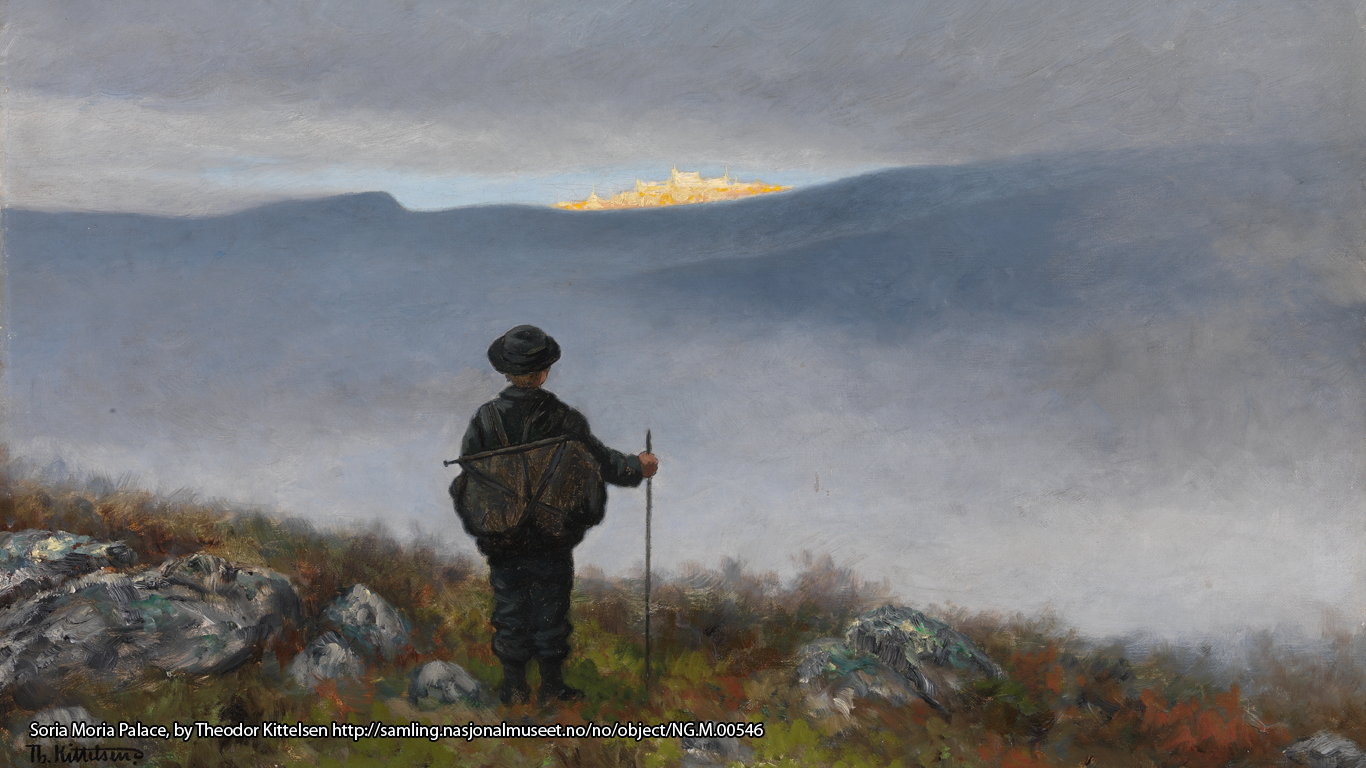

The first illustrated edition of Norwegian Folktales did not appear until 1879, more than thirty years after the publication of the first tales. Asbjørnsen commissioned a number of artists, such as Theodor Kittelsen, Erik Werenskiold, Hans Gude, Adolf Tidemand, and Otto Sinding to depict the tales.[17] The philosopher Marcus Monrad felt a measure of unease: “The Norwegian folk-spirit had expressed itself in the folktales. To interpret them in pictures also bore a great responsibility.”[18] His concern appears to have been unnecessary; the illustrations produced are some of the best-known, most well-loved of any produced in Norway. In fact, some of the illustrators are no longer remembered for much beside their folktale illustrations. And these days, very few people own unillustrated editions of “Asbjørnsen & Moe” as the collected folktales and legends has become known.

Today, it is difficult to exaggerate the significance and the influence of Asbjørnsen and Moe. Most Norwegian households possess at least one edition of their collected tales; its distribution rivals that of the Bible. On a more formal level, too, Asbjørnsen’s and Moe’s work—continued by Moe’s son Moltke (1859–1913)—led to the establishment of folkloristics as a discipline at the university in the capital city; a year after Moltke’s death, the university established the Norwegian Folklore Archives, which is still in operation today. Finally, Asbjørnsen and Moe inspired a veritable army of folklore collectors who worked and continue to work in their wake, collecting and publishing the remaining material from the whole of the country.

Asbjørnsen’s and Moe’s contribution is not confined to Norway; they also define and constitute our world literature. Henrik Ibsen’s most famous work, Peer Gynt (1867) is based on the folklore that surrounds the boastful figure of Per Gynt who appears in Asbjørnsen’s text “Mountain Scenes” (forthcoming) from the second volume of his Norwegian Hulder Tales and Folk Legends (1848). More importantly, the tales of Norwegian Folktales are as significant as those of any other collection, as even Jacob Grimm asserted: they are “die besten Märchen, die es gibt”. And you remember the tale of “The Three Billy-goats Gruff,” don’t you?

References and Further Reading

[1] Munch’s anonymous review of Norske sagn has later been characterised as “one of the most serious ‘axe murders’ perpetrated upon any Norwegian author.” <https://nbl.snl.no/Andreas_Faye>

[2] Information for this section taken from Norges bibliografisk leksikon.

[3] Fourteen years old might seem like a young age to begin preparation for university, but both boys had already been confirmed, and were thus considered adults.

[4] Gjefsen 2001, p. 39.

[5] Grefsen 2001, p. 46. For details on fóstbræðralag, click here.

[6] Gjefsen 2001, p. 100.

[7] Gjefsen 2001, p. 101.

[8] Gjefsen 2001, p. 96.

[9] Gjefsen 2001, p. 96.

[10] Gjefsen 2011, p. 57.

[11] “[T]he Grimms did not travel about the land themselves to collect the tales from peasants, as many contemporary readers have come to believe. They were brilliant philologists and scholars who did most of their work at desks.” (Jacob and Wilhlm Grimm and Jack Zipes. The Original Folk & Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm: The Complete First Edition. Princeton UP, 2014, p. xxi.)

[12] Gjefsen 2001, p. 104.

[13] Gjefsen 2001, p. 107.

[14] Gjefsen 2001, p. 122.

[15] Gjefsen 2001, p. 197.

[16] Gjefsen 2001, p. 200.

[17] Moe had by this time withdrawn from the project in order to devote his time to his calling, and had in 1876 been ordained bishop of Kristiansand diocese.

[18] Skre, p. 129.

Gjefsen, Truls. Peter Christen Asbjørnsen: diger og folkesæl (Andresen & Butenschøn, 2001).

Gjefsen, Truls. Jørgen Moe: En biografi (Dreyer, 2011).

Skre, Arnhild. Th. Kittelsen. Askeladd og troll (Aschehoug, 2015).