The hulder-folk are a hidden folk in Norwegian folklore. Analogous to the fairies of other lores, they are just as tricksy, just as sinister, and just as powerful and magical.

One of the most disturbing aspects of hulder-folk behaviour, as well as being one of the most widespread, is the snatching of so-called Christian-folk. Hulders take infants, young women and men, and they will take older people. At times, their motives are quite apparent; at others, they are equally as obscure. Fortunately, the folklore tells us how to prevent being snatched, and there are a number of measures that will reverse a snatch.

When the hulder-folk snatch a young child, they leave one of their own offspring in its place in the cradle, a so-called changeling. There appears to be little reasoning behind this habit, although the appearance and behaviour of their own offspring might help us understand; in “The King of Ekeberg” they are presented as “incorrigible screamers with big heads and red eyes, of whom their parents sought to rid themselves as soon as they could.”

But children are not the only people taken by the hulder-folk. Sometimes they use subterfuge to secure themselves a spouse from the Christian-folk. “Berthe Tuppenhaug’s Stories” contains a couple of legends in which young girls are enchanted to believe they are marrying their sweethearts, when in fact they will be marrying hulders. In the first of these tales, the hulders deck the girl out in a fine wedding dress, and they bring silverware, and set the table with wedding fare. Fortunately for the girl, the dog fetches her real sweetheart, who soon discovers the truth of the matter. The prospective hulder-bridegoom in “An Evening by Andelven” is less subtle. He comes to her by night, offering gifts. However, Mari, the girl, is “unspeakably apprehensive,” and asks the farmer’s wife, Inger Margrete, how to be rid of him.

Boys, too, are subjected to the amorous affections of the hulder-folk. Sometimes, the match is consensual; more often, it is not. The tale that Marie tells the narrator in “Hulder-kin” begins with a hulder girl falling in love with Marie’s great-great grandfather (or great-great-great grandfather; she is not sure which) who has remained behind at the pasture to see the hulder-folk. “[T]he boy thought he would like her well enough,” and they are married.

A tale in “An Evening Hour in the District Governor’s Kitchen” is the other way around; here a dragoon, “a great handsome lad” falls in love with a hulder girl “so gorgeous that he did not think he could live unless he could have her.” He wins her – in a manner of speaking – and they are married.

“Done Properly” Hans (“for he used to say, ‘Everything must be done properly’”), in “An Evening Hour in the District Governor’s Kitchen,” is taken by some subterraneans who intend that he should marry their daughter. When he refused, “they finally took him and threw him out from a high knoll.” From that time on, he is followed and bothered by the invisible Kari Karina, his intended. While he is with the hulders, Done Properly Hans is also compelled to steal food for them. It so happens that the hulder-folk cannot touch food or drink that has been blessed with the sign of the cross. “You must help us here,” they tell him, “for this is ‘crickled’ on.” Having the Christian steal for them is certainly an innovative means of getting around their powerlessness in the face of Christian symbolism.

There are even more reasons that the hulder-folk snatch Christian-folk. The woman who goes willingly with the King of Ekeberg, to act as midwife for his Queen, meets her own maid in the mound, grinding meal in the kitchen. The same text mentions that nurse-maids are also stolen, to look after the children that the hulder-folk take, “and often kept […] forever.” Also, Åse in “Lunde-kin” disappears from her maternity bed, “and in her stead there lay an alder stump.” She is found much later, cleaning in a mound.

One of the most striking legends is of the farmer in “A Night in the Northern Mark,” who falls through the floor of his barn, into a place that is “unreasonably fine. Everything was of gold and silver.” This snatch has a purpose, though; for the cattle in the barn above the hulder-folks’ dwelling drop their excrement onto the dining table below. The barn must be moved, and the hulder-folk make their point emphatically by offering the farmer to eat at their table. When the farmer agrees to move the barn, he is released, and he receives help and protection from his invisible neighbours.

It is only the minority of snatches that are beneficial, however, and so there are a number of methods by which people may thwart the attempts of the hulder-folk. Ridding oneself of a changeling, in order to receive one’s own child again, is the most violent method. The formula, “whipping changelings for three Thursday evenings on the rubbish heap, or pinching their noses with glowing fire tongs,” is found in “The King of Ekeberg.” Remedies for older folk are not nearly so distressing. The girl whom the hulder is “courting” in “An Evening by Andelven” is advised to shoot some sulphur over her bed, which rids her of his nuisance. Shooting over the cabin is also enough to break the enchantment over the boy’s sweetheart, and scatter the subterraneans in “Berthe Tuppenhaug’s Stories.”

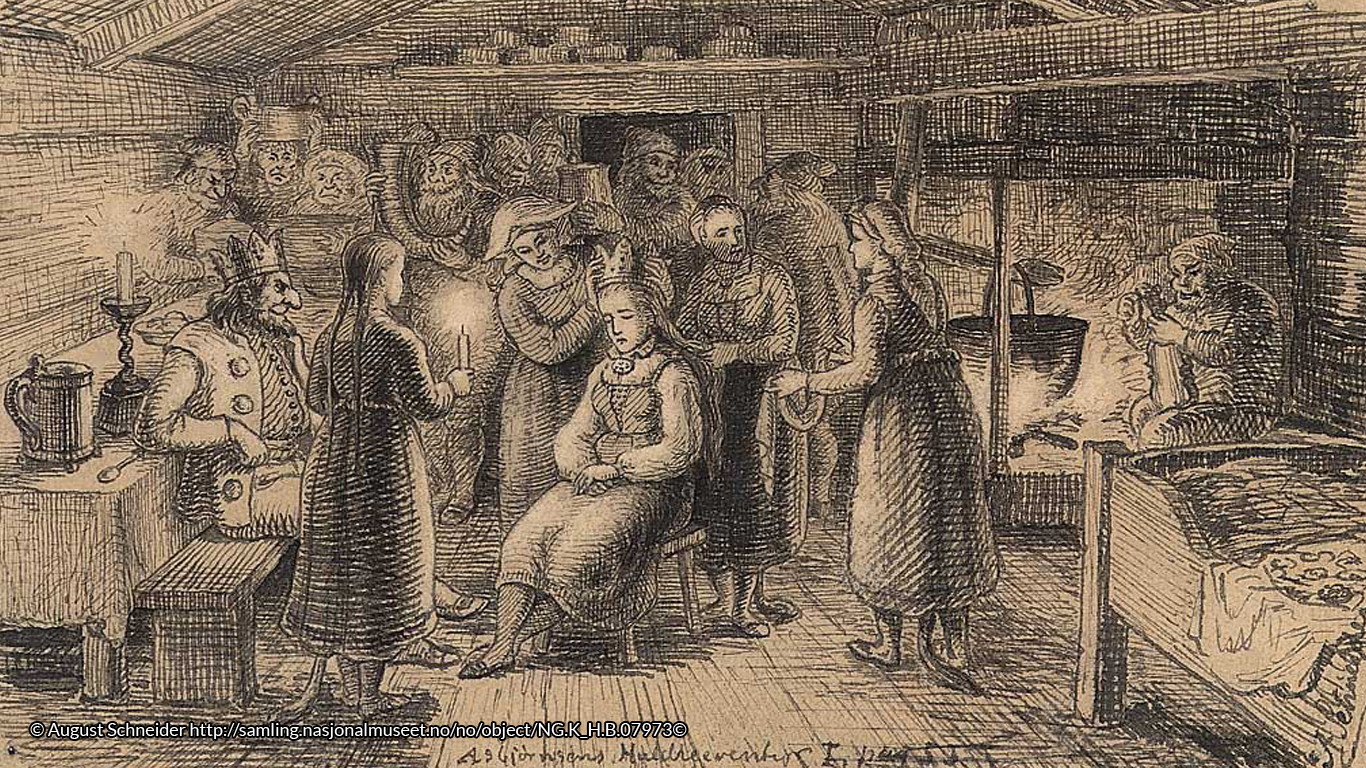

Illustration by Hans Gude. Source

There are also a number of ways of returning from the mound, once taken. The simplest is one that old Ola in “From the Mountain and the Pasture” discovers:

Once he said: “In Jesus’ name, shall I never return to Christian folk?” Then the hulder wept, and said that since he had mentioned the name that she could not have on her lips, they could not keep him any longer.

He is sent away.

The maid that the midwife discovers in “The King of Ekeberg” escapes her nightly jaunt to the mound by remembering to say her prayers, and singing a hymn before she goes to bed. A nurse-maid in the same text escapes, but the narrator is not sure how:

Whether it was because they had rung for her, or because she had placed her shoes backwards, or she spoke rashly, or she found a sewing needle in her tunic, I don’t remember. It is enough that she escaped.

The ringing of church bells is a motif that returns in a number of texts; but they must be rung for long enough. When Åse Lunde is discovered, cleaning for the hulder-folk, she complains that they should have rung a little longer for her, for she only had one foot within the village boundary, and was thus compelled to return to the mound when they stopped.

We are fortunate to have all these records from people who return from the hulder-folk. Without them, any one of us might be taken at any time, and there would be nothing we could do to escape the mound.

Do check out Simon’s new book: Erotic Folktales from Norway!

‘Once upon a time, in the 19th century, certain men began to travel the highways and byways of rural Norway, collecting the tales, legends, and fables that the local population had to tell them. Many of these tales were published almost at once, such as “The Three Billy-goats Gruff,” and “East of the Sun and West of the Moon.” Certain others tales, however, because of their plain treatment of the sexual side of human experience, were repressed. The manuscripts languished in the archives of the university for nearly a hundred years, before being brought into the light, and published in Norway.

Here are tales of witches, trolls, giants, soothsayers, and princesses; as well as tales of sinners, sextons, parsons, beetles, fleas, and mice. Even Adam and Eve make an appearance. Some of them are hilarious, others astonishing, with the odd cringe-worthy tale thrown in for good measure. All of the tales reveal the society that brought them forth—from a certain perspective.

This is the first time the collection has been translated into English.’

The book can be purchased here.

References & Further Reading

Asbjørnsen, Peter Christen. Norwegian Hulder Tales and Folk Legends, Vol 1. Christiania: 1845. (Simon Hughes, translator)

“The King of Ekeberg”

“Hulder-kin”

“An Evening Hour in the District Governor’s Kitchen”

“Berthe Tuppenhaug’s Stories”

“An Evening by Andelven”

“A Night in the Northern Mark”

“From the Mountain and the Pasture”

“Lunde-kin”