While Pan’s goat-like appearance makes him one of the most recognizable of the Greek gods, ambivalence surrounding the figure makes him harder to pin down.

One constant in Pan’s identity is his role as wild outsider. Usually he’s said to be the son of Hermes – though sometimes it’s Zeus or Dionysus – but his mother is almost always a wood nymph. This maternal connection to the wilderness, along with goatish looks that made him something of a laughingstock amid the gods, is said to have caused him to leave the civilized Olympian world for Arcadia, the central wilds of Greece’s Peloponnese region. In particular he’s associated with shepherds and goatherds active in the Arcadian pasturelands.

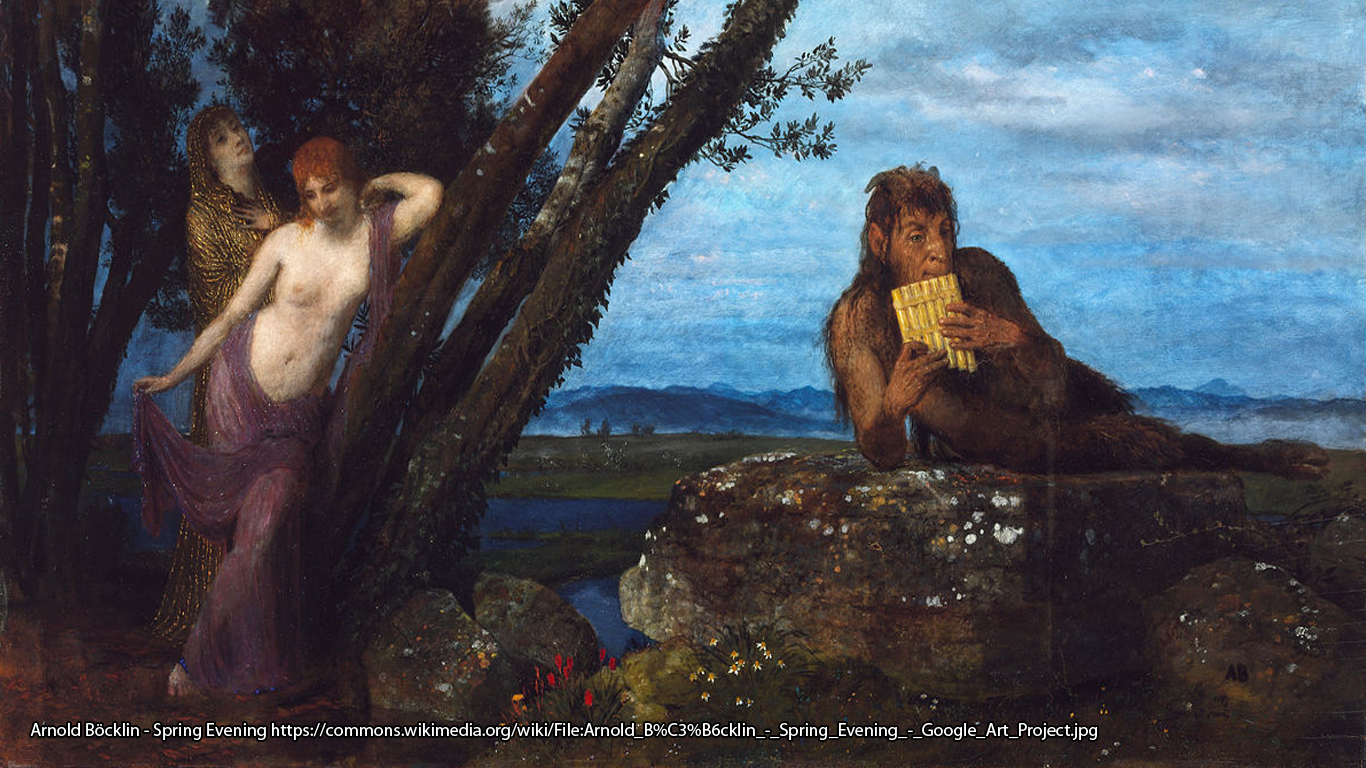

Probably the best-known story associated with Pan explains the origin of the panpipes as a product of the god’s unsuccessful pursuit of the nymph Syrinx. Fleeing Pan, she plunges into a river, transforming herself into a reed. Not knowing which reed represents his beloved, a desperate Pan pulls several from the vicinity, keeping them as a sort of sad consolation and binding them together into a set of pipes.

Pan’s amorous pursuits were legendary, and his aggressive sexuality was made clear in countless representations of the figure featuring an erect phallus. Though perceptions would change in the Christian era, this sexual aspect related to his original role as protector of herdsmen and was regarded positively, as representative of fertility in the flocks.

The only aspect of Pan to be feared would be that which gave rise to our word “panic.” Between his music-making and sexual adventures, Pan was known to make time for a regular midday siesta. Should noisy herdsmen chance to disturb the sleeping god, he would rise with a terrific shout causing flocks to stampede or scatter. A few stories make the consequences more dire still with an angered Pan transforming the disruptive herdsman into a wolf who would devour his own animals.

Pan is also well known for a story Plutarch told of the god’s death. This news was imparted via a disembodied voice calling to mariners at sea, commanding a particular sailor to announce to the residents of island of Palodes that “Great Pan is dead.” The news spread quickly and is taken seriously enough that Tiberius Caesar was said to have made an official investigation of the matter. Church historian Eusebius of Caesarea, noting that Tiberius reigned during the birth of Jesus, equates this announcement with the defeat of the pagan world through Christ’s birth. Eusebius noted, as further proof of his assertion, that Pan’s name is also Greek for “all,” making Pan a sort of universal embodiment of the entire pagan pantheon.

As an embodiment of everything pagan, the demonized Pan has been regarded as the visual prototype for the goat-like iconography of Satan. While we do see images of a hoofed and horned Satan popping up as early as the 9th century, this image is by no means universal. As demonology and witchcraft scholar Ronald Hutton points out, other common medieval depictions of Satan featured clawed feet, bat wings, or represent the Devil in the form of a dragon. Hutton believes the association has more to with a particular attitude toward Pan that flowered in the Victorian and Edwardian era.

In an age of rapid industrialization and destruction of nature and the old rural ways, Pan was sometimes employed by writers of the mid to late 19th century as a symbol of a lost pastoral world. He appears in this benign, gentler form in Kenneth Graham’s 1908 novel The Wind in the Willows, in the rather startling incongruous chapter “The Piper at the Gates of Dawn.” The elegiac attitude towards Pan, as a symbol of the lost innocence of the pastoral world, was also sometimes paired with a notions regarding the lost world of childhood – as in J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan books and play.

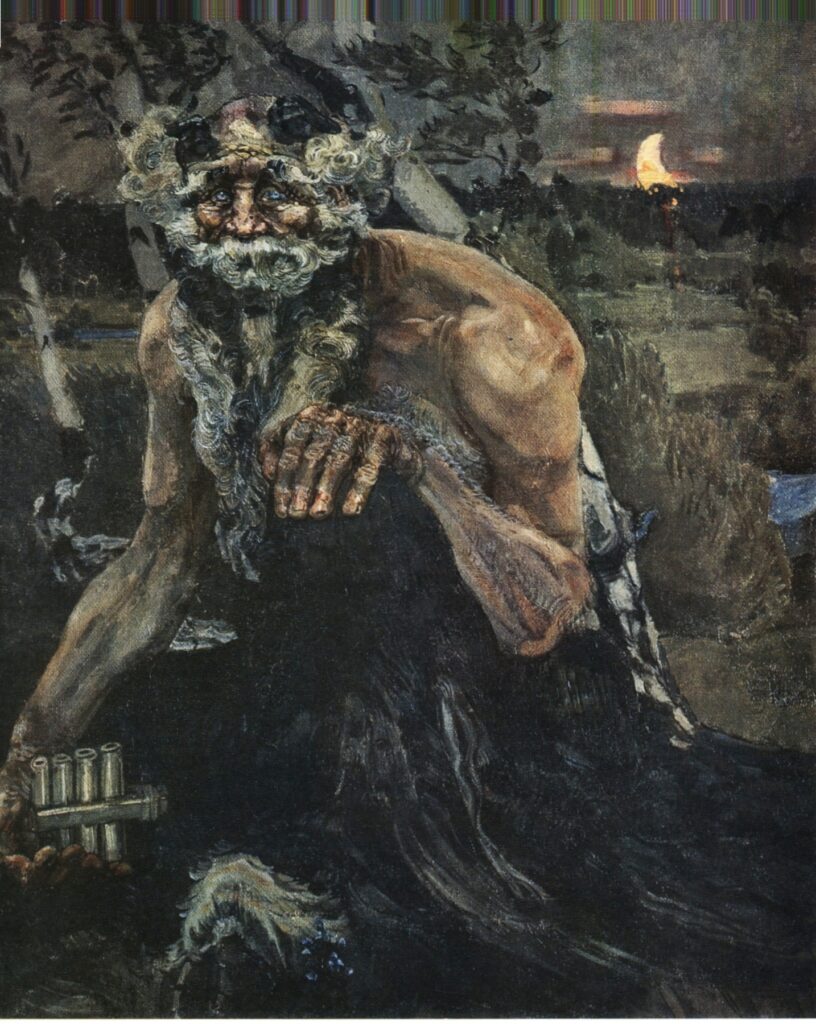

More commonly, however, the era’s attitude toward Pan was influenced by fin de siècle decadence, and the god was embraced in all his hyper-sexualized glory. Oscar Wilde called for his triumphant return in his poem “Pan — Double Villanelle,” while for others he became a symbol of nature’s darker aspect, dangerous urges and frenzy.

E.M. Forster employs the appearance of a Pan-like “wild boy” in 1911’s “The Story of a Panic” to create the titular panic among some very proper English tourists abroad in Italy. Short story writer Hector Munro (aka Saki), in his 1911 tale “The Music on the Hill,” likewise menaces a newlywed couple living in the country with a skulking feral Pan-like boy who seems to command a murderous stag. Other writers (Algernon Blackwood, Stephen McKenna, Forrest Reid, to name a few) used Pan as a catalyst for forbidden sexual encounters. Some imagined an actual resurrection of bloody rites to Pan in the Christian era, like Anglo-Irish writer Edward Plunkett (AKA Lord Dunsany) in his 1928 story “The Blessings of Pan.”

The literary and artistic popularity of the figure during this period also seems to have influenced those interested in a more literal resurrection of pagan or occult rites. Aleister Crowley composed his “Hymn to Pan” while staying in Moscow in 1913, later declaring it “the most powerful enchantment ever written,” even singling it out to it be read at his funeral. His acolyte the aeronautics engineer and magician Jack Parsons was also said to invoke Pan using Crowley’s hymn before igniting his test rockets during his years with Pasadena’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

Generally, this cultural obsession with Pan in the late 19th to mid-20th century might be said to reflect the period’s acute changes in sexual mores and the need for some sort of figure to embody these tensions. Without the same need in the present generation, we’ve seen Pan recede a bit from the limelight.

No longer the fraught, dangerous figure of turn-of-the century art and literature, Pan today is more easily perceived in his original form – not a dangerous stand-in for Satan, but a merry nymph-chasing figure, lounging about with his pipes, and napping. At least until foolishly awakened.

Recommended Books from #FolkloreThursday

References and Further Reading

Forster. E.M. (1959) “The Story of a Panic.” The Collected Tales of E.M. Forster. New York: Knopf.

Hutton, R. (2006). The Triumph of the Moon. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

S., & Munro, E. M. (1937). The Short Stories of Saki. New York: The Viking Press.

Stromer, Richard. “An Odd Sort of God for the British: Exploring the Appearance of Pan in Late Victorian and Edwardian Literature.”

Tonald, Eleanor. (2014). And Did Those Hooves – Pan and the Edwardians. Unpublished PhD Thesis. Victoria University of Wellington.