While the Pied Piper of Hamelin is undeniably a fairy tale, it’s uniquely grounded in real-world specifics – the date for one – June 26. That’s the date in 1284 when the town lost a significant portion of its population, a matter treated as fact in the first written allusion to the incidents, the initial 1384 entry in Hamelin’s town chronicle: “It is 100 years since our children left.”

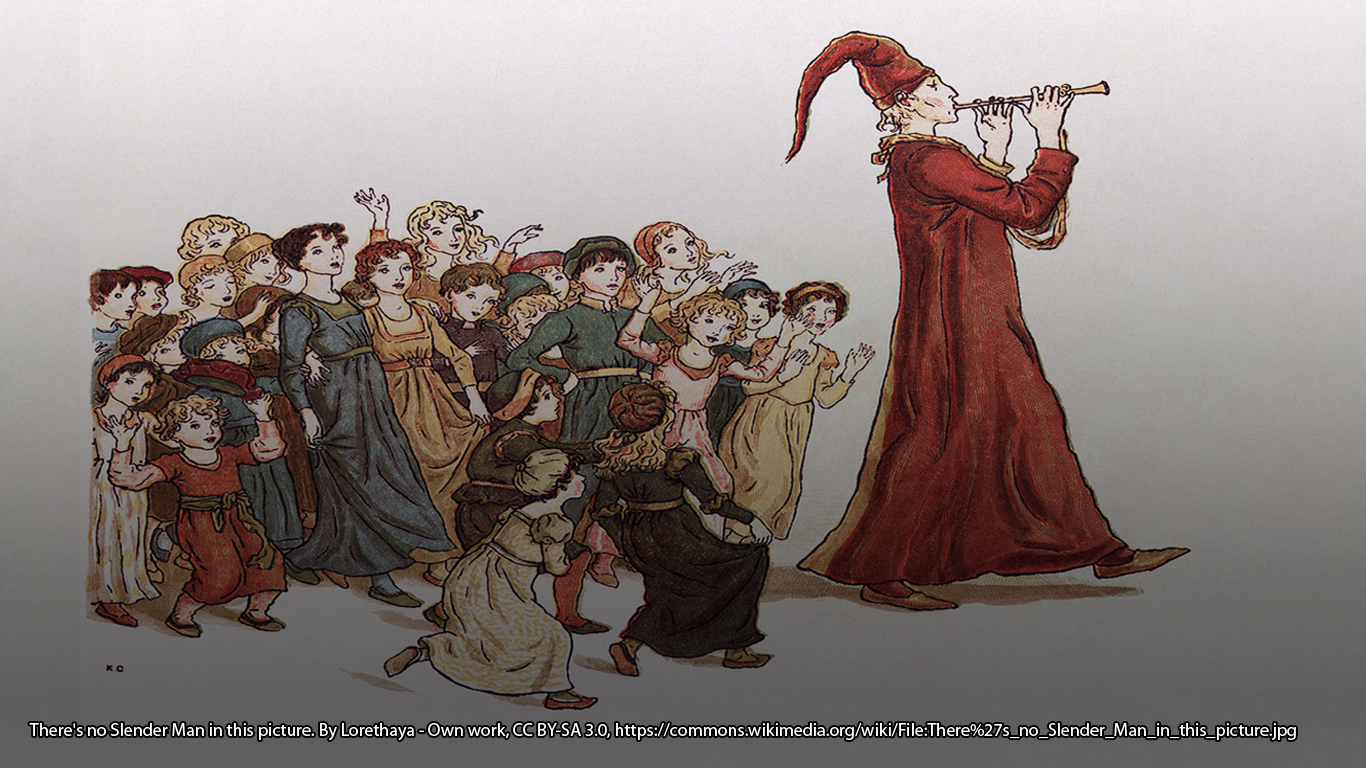

Presumably, the incident was so well known that it required no further explanation. It would have been familiar from oral tradition and had already been represented in a window installed in Hamelin’s Market Church in 1300. Though the window was destroyed in 1660, a painting from 1592 reproducing the window confirms some of the earliest elements of the story, showing a piper and children heading toward what appears to be a cleft in a mountain.

We know a few more details were fixed to the story by the 16th-century as they are painted on a gable of a building of the era that came to be known as “The Piper’s House.” It gives the number of children as 130. The loss occurred “through” a piper, it says, one dressed in pied, or multi-coloured, clothing. He led them off to “Calvary near the hills.” The allusion to Calvary, the site of Christ’s crucifixion, has been taken as an allusion to a sort of fate or martyrdom. Some time after this inscription was created, the final element of the story appears: the plague of rats.

A nutshell refresher on the story as it was finally consolidated: Hamelin is overrun with rats. A mysterious piper shows up offering a fix – for the right price. The mayor agrees. The stranger plays his pipe to draw out the rats and steer them into the Weser River to drown. The mayor reneges on payment, and the stranger leaves, only to return on June 26 to lead the town’s youth away into a cave in a mountain.

While we know the rats are merely an element of the storyteller’s craft (because rats actually can swim quite well), the sober entry in the town chronicle and stained glass commemoration of the event only 16 years after the fact, as well as the specificity of the gable inscription all argue for a real-world tragedy that calls for explanation.

So what answers have been proposed?

On theory has to do with the plague. Here the Piper is simply a symbolic representation of the Grim Reaper. In reference to the plague, Death was frequently represented as a musician in the danse macabre trope. But the black death did not arrive in Europe until 1347, 50 years after the incident.

It’s also been suggested that Hamelin’s youth left to take part in the Children’s Crusade, an effort to retake the Holy Lands not by warfare but the evangelizing presence of children. However, the Children’s Crusade was supposed to have happened in 1212, not 1284. How or whether the crusade happened at all is also subject to debate.

A more attractive theory relates the loss to the medieval dancing plague or dancing mania, a form of mass hysteria during which groups ranging from dozens to thousands were seized by an uncontrollable desire to dance or leap about wildly for days, weeks, or even months at a time – usually to the point of exhaustion and sometimes death.

This theory at least fits into the appropriate chronological window as the dancing mania afflicted mainland Europe beginning in the 11th century and lasting in some places into the early 17th. And it keeps the Piper as a literal musician leading a sort of dancing processional out of the city.

Those overtaken by the dancing mania were often said to travel while dancing. The Hamelin story seems not so different from what happened in 1257 in the German town of Erfurt, a couple of hours to the south. There, it’s reported that 1,000 children left the town furiously dancing, leaping, and singing, traveling 15 miles to the town of Arnstadt. Most of them, however, did return.

Adherents to this theory suggest that since the mania proved contagious, Hamelin might have hired a piper to lead the dancers beyond the city walls to prevent citywide infection. Perhaps it was conceived as some temporary measure but some unexpected evil befell the children once they were removed. But the dancing mania itself is so little understood that it hardly feels like a rational answer to our question.

One of the most widely accepted theories posits a mass emigration. This explanation understands the so-called “children of Hamelin” metaphorically as “those who belong to Hamelin,” a usage more commonplace in German. It suggests that a generation of youths, young men, or young families left en masse to seek their fortunes in more promising lands, namely Baltic regions to the northeast (the former Pomerania and East Prussia), Morovia (now the Czech Republic and Silesia), or Transylvania (Romania). All of these areas were settled by German migrants during the period in question. The Grimms’ version, which itself is supposed to have been synthesized from 11 earlier sources, explicitly mentions the last, saying:

“Some say that the children were led into a cave, and that they came out again in Transylvania.”

In the emigration scenario, our Piper would have been the figure historically known as a Lokator (A Latinate coinage meaning “re-locators”). These individuals were employed by nobility to recruit military, agricultural and trade workers needed to colonize under-populated or hostile areas under their rule. The Lokator would have arrived as a stranger, perhaps in a foreign uniform or brightly dressed to attract attention, and may have announced his presence in the town with musical fanfare. The pipe-playing of the folk tale could have thus been a sort of “song and dance” likely to take in younger, gullible folk eager to enjoy the promised riches of these eastern lands.

This last theory seems the most reasonable. But ascribing the Piper’s dress and music-making to the Lokator, while interesting, may be over-burdening the theory a bit. The story is a folk-tale, after all, and the motif of enchanted music used to seduce mortals into another realm is a staple of fairy stories throughout Europe. It is, like the element of the rats, quite likely a bit of embroidery by storytellers steeped in such lore.

In the early years of the story’s evolution, the seductive music could also be the most psychologically compelling element of the story, healing wounds in a community that suffered this loss. Regardless of the cause of the tragedy – through plague, Children’s Crusade, dancing mania, or mundane recruitment efforts – ascribing this tragedy to an irresistible supernatural agency might relieve the sense of guilt of those remaining behind. And for modern audiences, the magic piping does, after all, make for an engaging tale – one that’s lived to mark its 735 anniversary this month.

Recommended Books from #FolkloreThursday

References and Further Reading

Florescu, R. (2005). In Search of the Pied Piper. London: Athena Press.

Gutch, E. (1892). “The Pied Piper”, Folkore, 3(2), 227-252.’

Hecker, I. F., & Babington, B. G. (1835). The Epidemics of the Middle Ages. London: Sherwood, Gilbert and Piper.

Humburg, N. (1990). Der Rattenfänger von Hameln: Die Berühmte Sagengestalt in Geschichte und Literatur, Malerei und Musik, auf der Bühne und im Film. Hameln: Niemeyer.

Manchester, W. (2014). A World Lit Only by Fire: The Medieval Mind and the Renaissance Portrait of an Age. New York: Sterling Publishing.

Tatar, M. (2019). The Hard Facts of the Grimms’ Fairy Tales. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

“The Pied Piper of Hameln.” (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.pitt.edu/~dash/hameln.html

Florescu, R. (2005). In Search of the Pied Piper. London: Athena Press.