The parts of folklore which appeal to us are deeply revealing. For the Romans wolves played a vital part in their myths, about the world and about themselves.

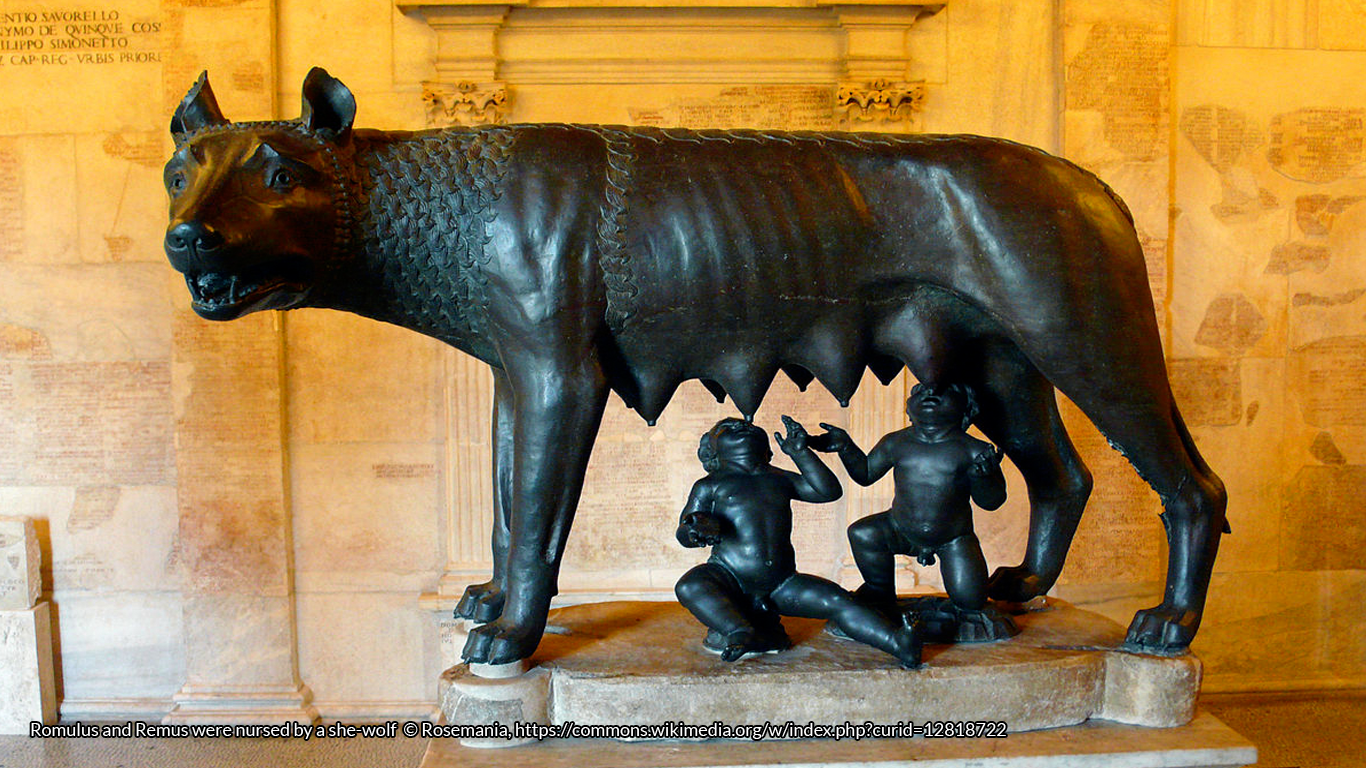

One of the defining symbols of ancient Rome is a remarkable piece of animal folklore. The image of it is still to be seen everywhere in Rome: The twins Romulus and Remus crouching beneath a she-wolf and suckling her milk.

When Amuleis drove his brother Numitor from the throne of Alba Longa, so the story goes, he forced the deposed king’s daughter, Rea Silvia, to become a Vestal Virgin. This would ensure the rival bloodline would die out. As other religions have proved though, abstinence is not always a 100% effective form of contraception. Rea Silvia fell pregnant and gave birth to twin boys, Romulus and Remus. When asked who the father was she claimed it was the god Mars.

As other religions have proved though, abstinence is not always a 100% effective form of contraception.

For this Rea Silvia was imprisoned. And the boys were placed in a basket and floated down the Tiber. Like so many boys floating on rivers in baskets these ones were destined for great things. On the banks of the Tiber the boys in the basket were discovered – by a she-wolf. She suckled and cared for the boys until a shepherd came to the rescue and raised them in human ways.

The stories we tell about ourselves are most revealing. For the Romans what did they see when they looked at the babies and the beast? The sons of a warlike god and a mortal imbibing animal strength from their adopted mother. Their descendents, those who looked on the statue, would know that they had the best of all worlds – human wit, animal power, and that divine spark which would give them Imperium sine fine – An Empire without end!

Here we will be examining not only the grand myths of Rome but her wolf folklore; the little stories shared by both farmers in their huts who heard the howls at midnight and learned men in libraries who never saw a wolf in their lives. Folklore is a way of understanding the world. It is not always right in all aspects, but is very rarely wholly wrong either.

For instance Livy tells us that the wife of the shepherd who raised Romulus and Remus may have been a prostitute.

“He took the children to his hut and gave them to his wife Larentia to bring up. Some writers think that Larentia, from her unchaste life, had got the nickname of “She-wolf” amongst the shepherds, and that this was the origin of the marvellous story.” Livy, Ab Urbe Condita 1.4

A lower class prostitute was known as a lupa – a she-wolf. Either this is a doubling of theme common to folk tales or a hint at the real she-wolf who suckled the founders of Rome, one who had to be erased from the boundless Empire’s supposedly glorious past.

The notion of human children being raised by animals is not unique to Rome’s founders. Aelian’s delightfully non-specific text, Historical Miscellany, gives us Cyrus nursed by a dog, Telephus and Heracles by a deer, Pelius and Tyro by a horse, Alexander son of Priam by a bear, and Aegisthus by a goat. There are also convincing reports that humans raised in the wild exist in real life as well as in fiction, though obviously startlingly rarely.

The wild wolf was an animal companion to the god Mars. Since he was the father of Romulus and Remus it makes sense that a she-wolf would come to the rescue. The notably martial race that was the Romans found the wolf coming to their aid as a divine messenger. When the Romans and Gauls were drawn up for battle:

“A hind, pursued by a wolf that had chased it down from the mountains, fled across the plain and ran between the two lines; they then turned in opposite directions… the wolf towards the Romans. For the wolf a passage was opened between the ranks, but the hind was killed by the Gauls… the Roman side called out: ‘that way flight and slaughter have shaped their course, where you see the beast lie slain that is sacred to Diana; on this side the wolf, sacred to Mars, unhurt and sound, has reminded us of the Martian race and of our Founder.” Livy, Ab Urbe Condita, 10.27

Livy reports numerous times when a wolf would wander inside the walls of the city as a portent, either good or evil. “A wolf entered the City through the Porta Esquilina, the busiest part of the City, and ran down to the Forum; it then ran through the Tuscan and Cermalian wards, and finally escaped through the Porta Capena almost untouched.” At other times a wolf found its way to the Capitol, where there was a statue of Romulus. Each of these events prompted an animal sacrifice to ward off the wrath of the gods.

Livy reports numerous times when a wolf would wander inside the walls of the city as a portent, either good or evil.

Cicero spoke once about a terrible storm when many of the statues of the gods were struck by lightning: “Even Romulus, who built this city, was struck, which, you recollect, stood in the Capitol, a gilt statue, little and sucking, and clinging to the teats of the wolf.” This was thought to presage civil disorder and destruction so entwined had the Wolf, the Boy, and the City become.

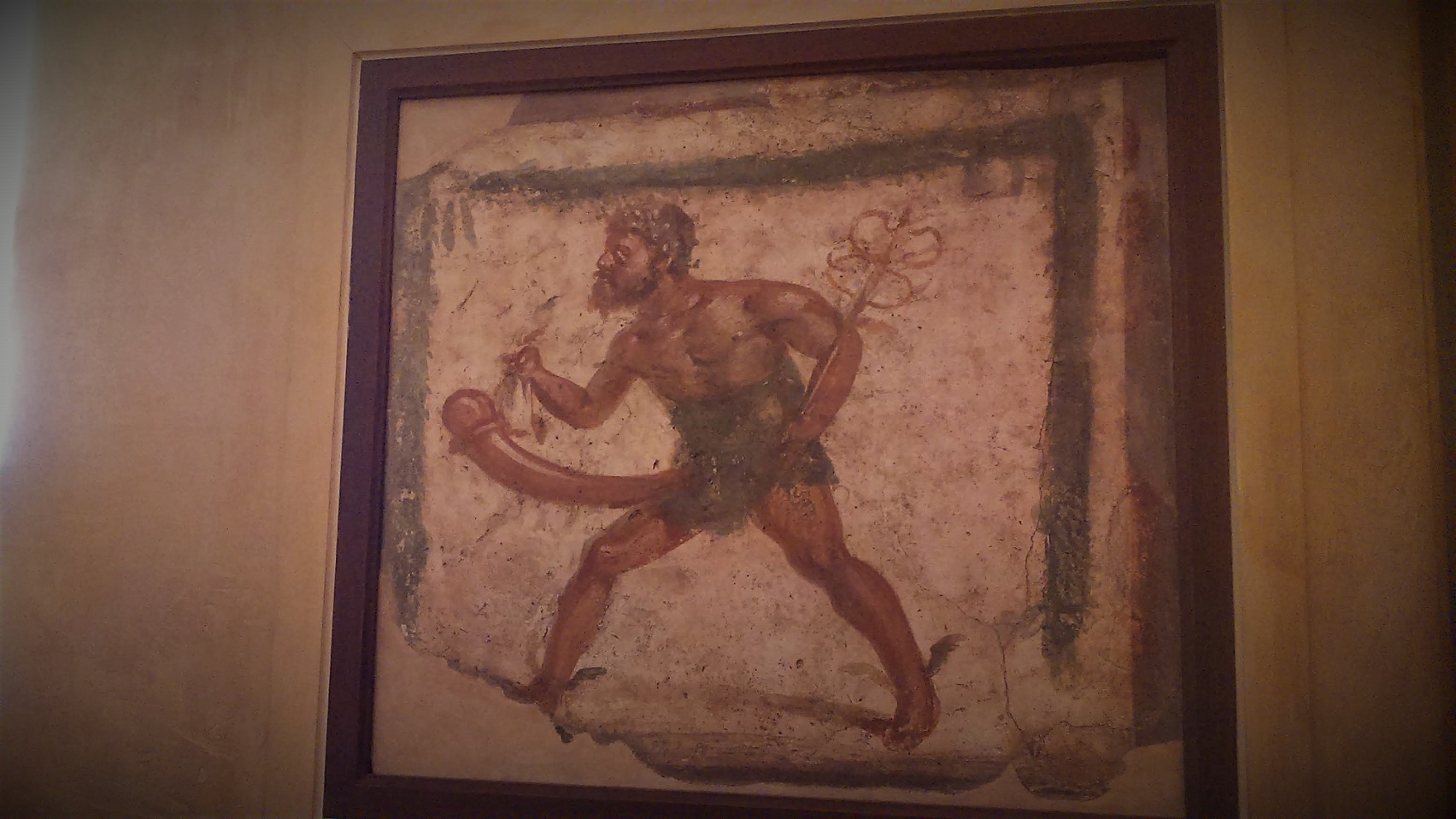

Even without the prompting of the gods to take action there was an annual wolf festival – the Lupercalia. Running for half of February this religious festival was designed to purify the city and avert evil. The etymology of the name Lupercalia is somewhat obscure. It would seem to spring from lupus meaning wolf, but it was held in honour of the god Lupercus, the Roman equivalent of the Greek god Pan. Lupercus’ temple however was built on the site of the cave where Romulus and Remus were suckled – the Lupercal. Wherever the name came from the festival was a major event.

The rites of the event were performed by the priests known as Luperci, Brothers of the Wolf. They would sacrifice two goats and a dog and from the skins of the goat make whips, dipping them in milk to represent the wolf’s milk.

“At this time many of the noble youths and of the magistrates run up and down through the city naked, for sport and laughter striking those they meet with shaggy thongs. And many women of rank also purposely get in their way, and like children at school present their hands to be struck, believing that the pregnant will thus be helped in delivery, and the barren to pregnancy.” Plutarch, Life of Caesar

Our best sources for less mythic Roman animal folklore are those authors who collected facts and stories in compendious works. As in so many things Pliny the Elder, 23-79AD, is our best source and witness to the state of knowledge in Ancient Rome. In the chapter of his Natural History devoted to wolves Pliny tells us that:

“In Italy also it is believed that there is a noxious influence in the eye of a wolf; it is supposed that it will instantly take away the voice of a man, if it is the first to see him.”

The idea of a gaze having power still exists in the Mediterranean. People with blue eyes are said to have the Evil Eye, their glance cursing those that it falls on. Certainly the person who is looked on by a wolf may well be sufficiently scared as to lose their voice. This folk belief was also the source of a Roman saying for a phenomenon we are all familiar with. When someone fell silent because a new person had just entered the room – “Lupus est tibi visus,” you have seen the wolf.

Pliny also tells us that the wolves of Africa are lazier than their more vigorous cousins in the frigid North. This belief reflects the idea in the ancient world that heat was enervating. The supposed effeminacy and weakness of the people in the South was due to the effects of the hot sun on them. If it was true of people then, naturally, it would be true of the animals too.

Pliny has some other interesting ideas about wolves. He tells us that in extreme hunger they will eat soil. Many animals do eat soil on purpose but generally not from lack of food. Eating soil can help make up for some dietary lack of minerals. Was this tale concocted to explain an observed behaviour?

The largest part of Pliny’s work on wolves is dedicated to lycanthropy – men turning into wolves. The Romans used the word versipellis to describe several types of madness. It literally means ‘changing skin’ and Pliny explains the origin of the term in what he considers the unbelievable accounts of the Greeks.

“The Arcadians assert that a member of the family of one Anthus is chosen by lot, and then taken to a certain lake in that district, where, after suspending his clothes on an oak, he swims across the water and goes away into the desert, where he is changed into a wolf and associates with other animals of the same species for a space of nine years. If he has kept himself from beholding a man during the whole of that time, he returns to the same lake, and, after swimming across it, resumes his original form, only with the addition of nine years in age to his former appearance. To this Fabius adds, that he takes his former clothes as well.”

To this Pliny adds, unironically enough, “There is no falsehood, if ever so barefaced, to which some of them cannot be found to bear testimony.” Which is something all those interested in fortean matters should always remember.

Wolves embody many characteristics that the Romans would wish to believe about themselves. Wolves are pack animals, they work together for the common good just like the lock-step legions of the Roman army. And yet the Romans were not blind to how their wolfish nature could be a bad thing for those who fell under their control. A wolf makes a poor shepherd. This ambiguity flows through Roman folklore.

Recommended Books from #FolkloreThursday

References & Further Reading

Pliny the Elder, Natural History http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.02.0137:book=8:chapter=34&highlight=wolves

Ralph Haussler, Wolf and Mythology – http://ralphhaussler.weebly.com/wolf-mythology-italy-greek-celtic-norse.html

Aelian, Historical Miscellany, Loeb Translation

Cicero, Against Catiline, http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.02.0019:text=Catil.:speech=3:chapter=8&highlight=wolf

Plutarch, Life of Caesar, http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/e/roman/texts/plutarch/lives/caesar*.html