Trolls come in many shapes and sizes. No one description can fit them all. Is there a core of trollness which we can uncover?

Sitting in his home Troldhaugen (“Troll’s Hill”) in Norway Edvard Grieg composed the music for the play Peer Gynt. The most famous section of this is In the Hall of the Mountain King. This particular king under the mountain is a troll who asks the central question of the play: What is the difference between a troll and a man?

What is the difference between a troll and a man?

Before we can answer this we must look at some of the depiction of troll in art, fantasy, and folklore.

By far the most common use of the word troll today is in relation to users on the internet who exist for no other purpose than to cause upset. These take their name from the horrible trolls of fairy tales. When you least expect it (crossing a bridge for goats/checking Twitter for us) they pop up from their lair (dank hole/parents’ basement) to ruin your day.

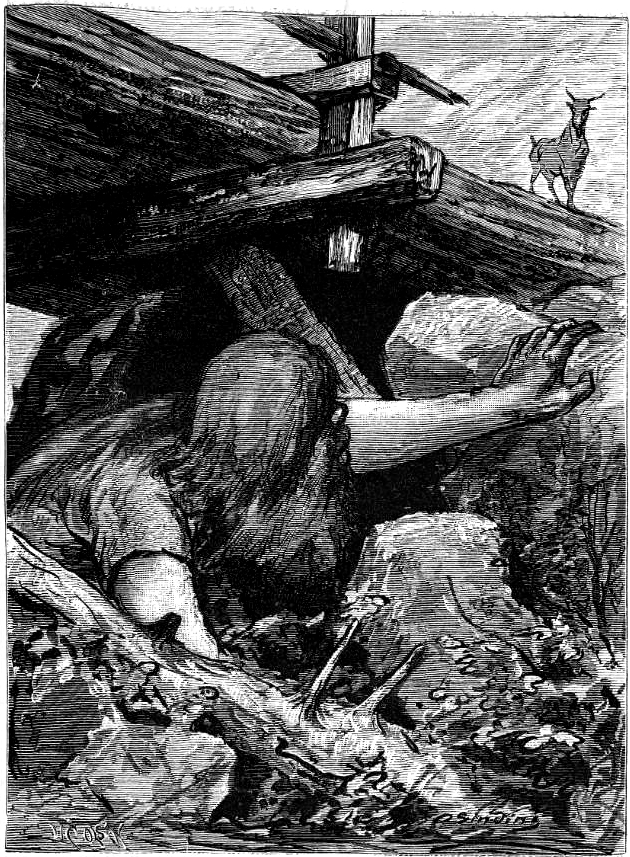

“Cave troll!” A character in Lord of the Rings bellows as a hulking, grey skinned monster lumbers into view. In the 2010 Norwegian mockumentary Trollhunter the trolls of the bleak North are also vast and shambling and stupid. It injects them into the natural spaces of the country. This is a reversion, as we shall see, which separates them from how they appeared in much the 20th century.

Few people outside of Scandinavia would associate the cute and bumbling figures of the Moomins with trolls, but in the original they are called Mumintrollen. Equally un-troll-like are the whacky haired Dam Trolls which have undergone sporadic popularity since the 1960s.

How can creatures as diverse as these, and others we will examine, fall under the same name?

It turns out that this confusion of beings is found in the earliest sources too. The word troll with its modern sense of a slow-witted and ugly beast comes from Old Norse, but can be traced back to Proto-Germanic words meaning giant, monster, or fiend. The Proto-Indo-European roots are even simpler – run, flee, escape.

Trolls are a fixture of the Scandinavian folk landscape and it is there that we must search for their essence. They seem to be linked to the jötnar, the race of giants who were refused access to Asgard by the Norse gods. This puts the creation of trolls as earlier than mankind. There is no clear definition of a troll in the old tales however. The name troll is used for the jötnar themselves, mountain dwellers, ghosts, and ugly people. From this inchoate idea of what a troll is would develop one of the great tropes in fantasy and folktale.

Yet we should not just think of trolls as figments in imaginary worlds. When King Magnus Haakonsson modernised the laws of Norway in 1276 he made it illegal to attempt to wake “mound-dwellers,” identified in the laws by the first recorded use of the word “troll.” When we think of the great burial mounds, barrows, of the Norse world we can see the link between massive earthy creatures and the ethereal haunting of ghosts. In Snorri Sturluson’s 13th century Skáldskaparmál he describes a meeting with a troll woman who describes herself in the following way:

“They call me Troll; Gnawer of the Moon, Giant of the Gale-blasts, Curse of the rain-hall, Companion of the Sibyl, Night-roaming hag, Swallower of the loaf of heaven. What is a Troll but that?”

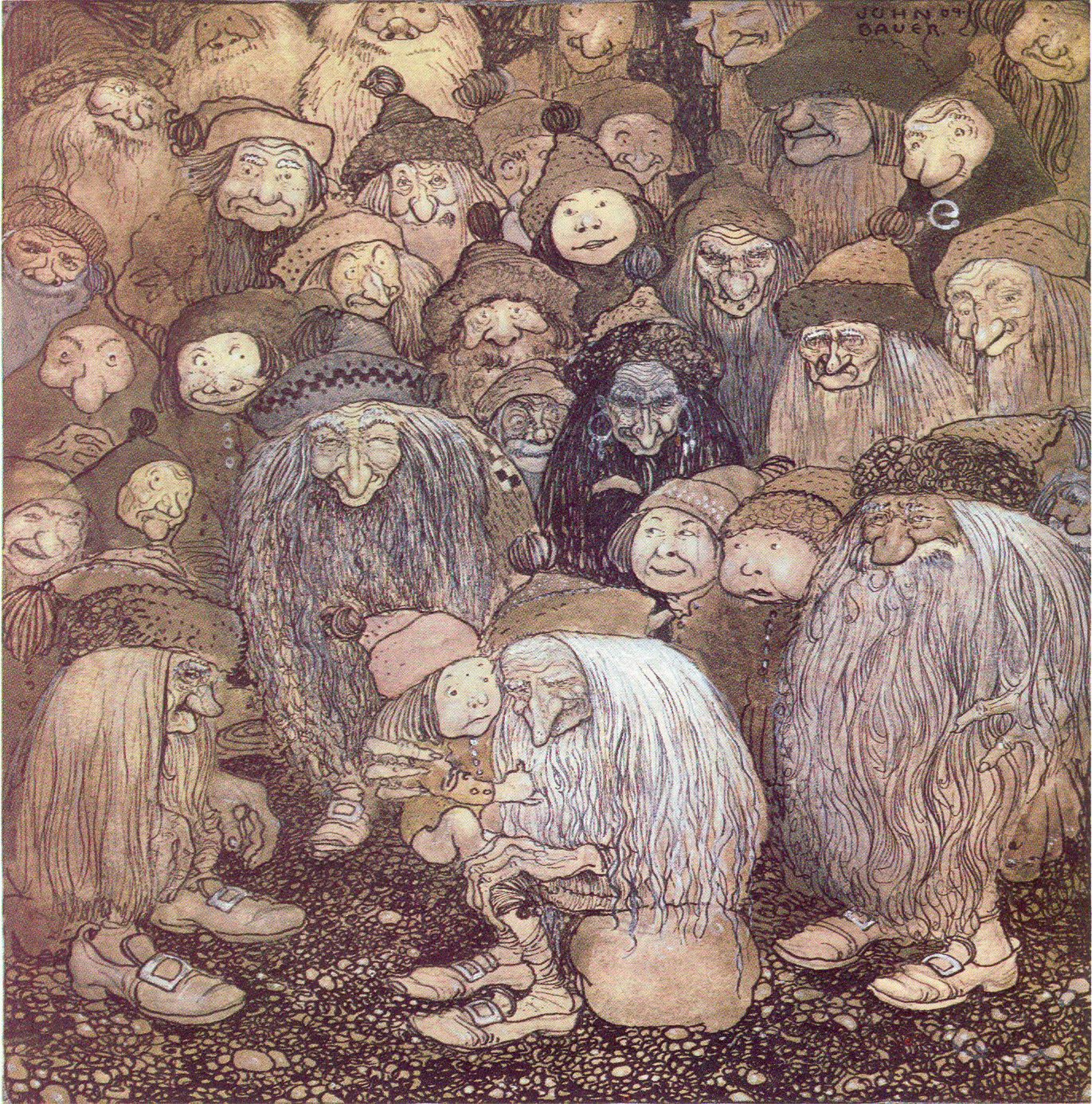

The idea of trolls as beings living outside of society, in monuments from a dark past, shaped how they are seen. Some trolls are very like us, they live in families, but are unlike us, living apart from us. In folk tales trolls would come out of the primordial forests and steal away Christian children, replacing them with their changeling troll babies. Is this some remnant of a fear that the old Norse way, the old Norse gods as represented by the jötnar trolls, would return to replace modern Christianity? It is surely no coincidence that trolls can be driven away by the ringing of church bells.

In the Saga of Ketil Trout trolls are a recurring theme. We are told how Ketil the hero is born to a father who is half-troll. Ketil then meets up with Hrafnhild the troll and fathers a child on her. This child is Grim Shaggy-Cheek, named for the hideous hair on his face. Humans are therefore not all that different from trolls. Yet in the saga Ketil is told “It is evil that you should love that troll.”

So what are we to make of trolls? Are they giant ogres who grunt and drool? Or are they dwellers of the ancestral forests whom it is possible to interbreed with? Do they live alone in burial mounds? Or do they live in communities in the woods and forests and steal human children to raise as part of their family?

One idea which may help our study of trolls is the idea of the ‘bergtagna’ – those taken to the mountain. It was said that trolls would sometimes abduct people away to their homes in the mountains, only to return them later in an altered state. These poor folk, almost certainly people suffering mental illness, are another sign that the troll myth refers to those cut off in some way from the human community.

So to return to the question at the beginning, what is the difference between a man and a troll? In Peer Gynt the answer given is “Out there, where sky shines, humans say: ‘To thine own self be true.’ In here, trolls say: ‘Be true to yourself and to hell with the world.'” Perhaps this is a fitting definition for both old trolls and new. Trolls will continue to fulfil many roles in fiction and reality. Their very lack of definition means they will always have a niche to fill so long as there is a sense of otherness we need to explain and explore.

Book recommendations from #FolkloreThursday

Trolls – An unnatural history. John Lindow, 2014, Reaktion Books

Troll – New World Encyclopedia. (http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Troll)

The Saga of Ketil Trout, Translated by Gavin Chappell, 2011. (http://www.germanicmythology.com/FORNALDARSAGAS/KetilsSagaChappell.html)