I have a confession to make: I’m a bibliophile. I have a small collection of very, very old books and still count the moment I touched a middle ages herbal worth more than my apartment as a highlight of my life.

I mean, this surely doesn’t come as a shock here on #FolkloreThursday, albeit it does raise a few eyebrows in my private life (especially if you consider that I’m far from an old wise librarian, since I masquerade as a heavy metal guitar player working in the video game industry with a penchant for learning languages). But one of my hobbies is visiting interesting bookshops and fairs, where you can often find weird and quirky books and comics. And it’s exactly at one of these fairs that I stumbled upon this book.

Now, Gino Bottiglioni’s Legends and Customs of Sardinia immediately caught my attention. A pre-Fascist era book on Sardinian folktales, written before my grandparents were even born, and it’s framed from a linguistic studies point of view? By the heathen shores of Asa Bay, I do believe I hit the jackpot.

Picture this: it’s 1914 and you’re a young professor that managed to build a not-too-shabby reputation in the field of dialectology, teaching at universities and publishing articles on the chaotic mess that is the Italian dialectal continuum. You grew up in Tuscany and perfected your studies at the very respected university of Pisa, but winds of war are blowing over Europe and, more importantly, Florence and all the other comuni aren’t quite interesting enough from a linguistic or folkloristic point of view. It’s time to pack your books up and find a new place to explore, but where?

Enter the island of Sardinia. A massive chunk of rock and weeds smack dab right in the middle of the Mediterranean, Sardinia isn’t exactly Paradise on Earth. “The fierce beauty of the Galluran mountain landscape,” Gino will write of the homonymous region, “can best be experienced by taking the carriage road from Terranova to Sassari, crossing amazing masses of rocks and dense oak, holms and cork woods, often with gaping red gashes in their trunks that bring to mind images of human bodies, wounded and bleeding. It is […] a territory that’s tough to cross, but in which one can enjoy all the horrid native beauty of Sardinian lands.”[1] Arcadia this ain’t, but Gino is a man who can appreciate more than a pinch of desperate desolation in his travels.

He immediately fell in love with the island and spent the rest of his career writing about its dialects and its people. And it wasn’t a simple task: prior to the Sixties Italy was an extremely poor country, an agricultural society with significant levels of illiteracy and a population trying to emigrate to anywhere but the peninsula. Now, if you consider that Sardinia was thought of as too wild and unlivable even by Italian standards, you can get a picture of the kind of guy Gino was in his prime. But it’s also an extremely unique land, and extremely unique lands make for extremely unique folktales.

The book I’m sourcing from is a milestone, but we’ll see why in a second. It’s a reprint of the original 1922 study, yes, but it’s a very elegant anastatic edition – a 1:1 copy of the original version of the book, down to font choices and illustrations. And it’s a fascinating little thing: after a brief foreword by Enrica Delitala, researcher and professor of History of Folk Customs at the University of Cagliari, the author dives head-first into a summary of common themes throughout the 127 (!) folktales he gathered along his travels, neatly separated by dialect and area. And he immediately notices something.

There are no heroes in Sardinia. This isn’t a metaphorical description of how rough life on the island can get, but a literal fact: Sardinian folktales seemed to have no mythic knights or William Tells, and all traces of folk figures had disappeared from popular culture.

“There is a noticeable poverty of elements from ancient folklore, and I could not tell how much Sardo-Pater[2], Jolao, Josto or other mythological heroes of pre-Roman era Sardinia remain in the people’s consciousness. I haven’t found any trace of the tale of the Phoenician city of Tharros, and I could not confirm F. Corona’s theory behind the legend of the Iliesian rock. The Sardinians still know of ancient cities and untold riches, and they can guide me to those ruins if asked. But all memories of those times are lost.”[3]

There’s an underlying hint of sadness in his writing. And yet, Roman folklore didn’t seem to have replaced local traditions; the Romans came and went, with their thousand-year-and-more empire, without leaving much of a trace on the islanders’ consciousness. No, you know what really got the storytelling part of their brains going? Christianity.

The Church’s effort in completely erasing Italian pagan cultures is something that requires far more space than I have here, and admittedly I have a bone to pick regarding the topic. But Christian fervor swept through the island like a summer storm:

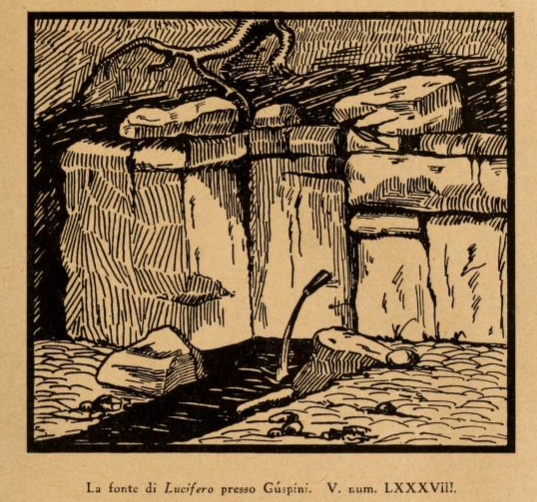

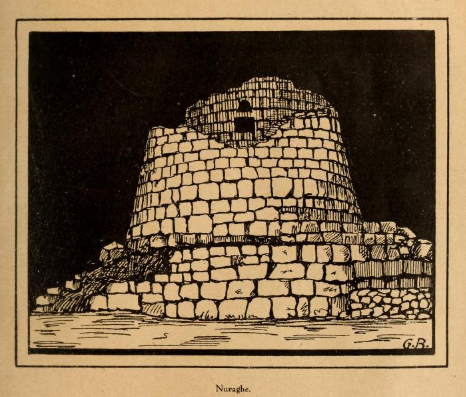

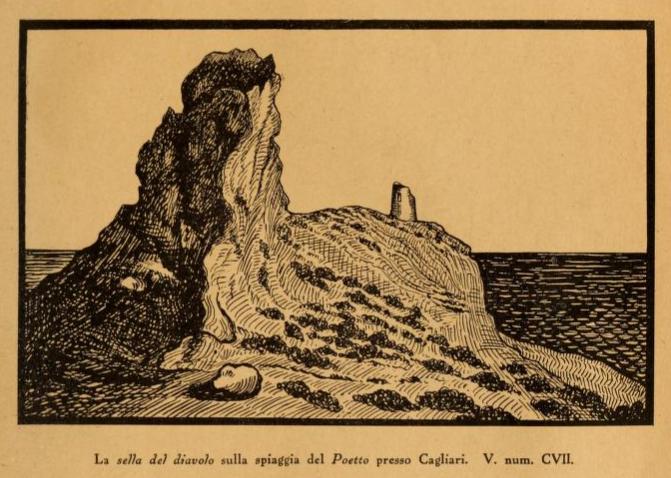

“The Sardinians’ imagination was blinded by the incoming Christian civilization, which wrestled with every single previous culture and won. Today, all Pagan monuments remaining throughout the island are considered to be home to the Devil, or became the foundation for a Christian legend; this happened to the Pagan temples of Terranova, or the Nuragic well of Paulilàtino, now thought to be the place where St. Christine disappeared. Ancient elements have been… Christianized, so to speak, and offer nothing specific to Sardinia, being little more than the same tales you can find in a thousand places throughout Italy”.

Even the Neolithic structures that litter the island, representing some of the oldest civilizations in Europe, were retrofitted into the all-encompassing Catholic faith, leaving just a trace of a mythical race of giant moving massive stones around (something you can find from Stonehenge to Easter Island). One specific original piece of folklore does remain: the domus de janas, a name used to refer to prehistoric tombs and dungeons peppered throughout the island, that local shepherds and townsfolk believed to be the last remnants of a civilization of elves – janas being a common dialectal name for the faerie folk; but whether they turned into evil spirits or are simply shying away from human contact depends on which area of the island you’re on.

But what makes this book a milestone isn’t just the poignant analysis of Sardinian folklore in the opening chapters. The thing that makes Legends and Customs of Sardinia a pioneering text is that Buttiglioni recorded all folktales in the exact way the people narrated them, making sure the text would include a phonetic transcription – a read-it-as-you’d-say-it text – of the original dialect with a parallel Italian translation. It includes geographical location of the tales, it’s divided along regional areas and each story is meticulously attributed, be the narrator a priest or a highwayman, with names and town of origin. It’s an excellent example of work done in the field, and an extremely important document both for the history of folklore studies and for the history of linguistics. But one of the two draws our attention more, right?

So: 127 folktales, some pages long, some as long as a single paragraph, but all gathered “on the battlefield”. There are the mischiefs of the janas, like in ‘The Elf with Seven Caps’, one of many tales told to Gino by a woman in Tempio; in this story a man steals one of the caps from an elf “with hands as white as snow”, hiding it under a sooty pot where the elf wouldn’t dare to look for fear of getting dirt on his skin. There are examples of Christian “revisionism” like in reverend Don Lorenzo Atzori’s The Golden Spring, where a hoofprint on a rock is attributed to St. George miraculously summoning a stream of water for all the fateful gathered around him. There’s local hauntings, living dead inhabiting castles and a weird re-imagining of Prometheus’ myth where St. Anthony donates fire to humanity by stealing it from the demons down in Hell, but my favorite apocryphal piece of the Bible is ‘The Birth of the Pig’: in it a pre-apple Adam fathers a significant amount of children and tries to hide them from God in a locked room. But God finds out and turns them into pigs, which according to the narrator is the reason why pigs are so similar to humans.

And there are interesting traits unique to Sardinia. Chief among them is an odd obsession with people turning to stone: the breaking of a rule bringing a terrible curse is nothing new in folktales, but it’s kind of interesting how many of those stories were created around human-looking rocks – and if there’s anything abundant on the island, it’s strange and warped rocky formations. Another recurring element are the Moors, which Sardinia had a… let’s say mixed relationship with, but the most unique thing is the Butcher Flies and the treasures they hide.

The Butcher Fly, or mosca macedda, is a fascinating cryptid. The best way I can describe it is a folkloristic re-imagining of a biblical plague: swarms of these flies are supposedly hidden in chests and barrels around the island, often as parts of riddles or traps for careless treasure hunters, and setting them free would mean wiping away entire towns. Their role seems to be primarily to instill a healthy dose of aversion to risk in the listener, like in ‘The Treasure of the Castle of Monreale’, where an evil lord hid his riches in a barrel and a swarm of Butcher Flies in another, and no explorer ever dared to take the chance.

Here’s where I’d start talking about hidden treasures, another peculiar common theme in these stories, but the article has already been running way too long. I could go on and on moving seamlessly from a topic to the next – most of these stories are interconnected, mixing curses and priests, devils and flies, told by common people rather than master storytellers. Common people who don’t seem to value some glorious golden age much, but would rather go with the flow, adapting to whatever culture they found themselves under without giving it much thought. There are fields to plow and sheep to shear, and even if there were something interesting buried beneath those ruins over there, that’s not a priority right now, is it?

Sardinia is a fascinating place with fascinating contradictions. It’s home to the oldest ruins in Europe and some of the oldest in the entire world, but it’s also a place living in the now, full of practical people and amazing food and beaches. This book isn’t available in English as far as I’m aware, sadly, and translating it would be a massive undertaking – one that would require time and energies I cannot afford. But the island is still there, and it’s still as magical as it’s always been. Pay it a visit sometimes. You can do what Gino did and explore the island on a bike, or enjoy a relaxing day amongst the waves. As long as you make sure you’re not opening any mysterious chest you stumble upon, I can guarantee you won’t regret it.

Recommended Books from #FolkloreThursday

Leggende e Tradizioni di Sardegna, G. Bottiglioni, Olschki, Geneva 1922

Notes

[1] Excerpt from Sardinian Life (Vita Sarda, Dessì, Sassari 1978), a book of letters Buttiglioni published shortly before his death which contains some amazing insights into turn-of-the-century life on the island.

[2] The Sardus Pater, Latin for Sardinian Father, was the central hero/god of the Nuraghe civilization. Son of the god Malkeris, which scholars identify with Hercules, he sailed from Libya and settled on the island along with a large expedition, having the name changed from Greek Ichnusa to Sardinia in his honor. While the story bears several resemblances to the Nordic Sagas, there are no texts recording it directly, and we can only trust third-hand sources – a description of the event was included in Sallust’s Historiae, but the work has tragically been almost entirely lost. Today Ichnusa is mainly known as the name of an excellent Sardinian beer.

[3] For the sake of readability, I’m condensing the translations down to a more direct text, as Buttiglioni has a massive soft spot for details and can reference dozens of folktales and theories in a single paragraph.