Folklore and tales form a gigantic living web that threads through our cultures and societies. I see it as analogous to mycelium, the fungal mesh beneath the ground: a gigantic, intricate system of connection that feeds and informs the trees and plants that sprout above the surface whilst quietly spreading, putting out feelers, thriving.

Mostly, when we walk in the forest, we’re not aware of the mycorrhizal network under our feet. We might spot an English oak here, and a sessile oak over there. We might observe what they have in common, whilst also noticing the differences in leaf shape or acorn style. These oaks are the stories and songs that emerge from our cultural commons. We can all marvel at their forms and enjoy their shade, but for those of us in this metaphor who like to dig beneath the leaf mulch, into the busy earth, finding and following the threads of folkloric mycelium is as big a thrill as any.

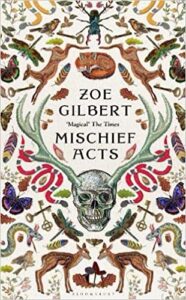

I found myself tracing just such threads while researching for my novel, Mischief Acts. It wasn’t the first time – as readers here will know, if you read enough folk tales and folklore, you are constantly discovering kinships, connections, ancestors and progeny. But Mischief Acts tracks Herne the Hunter through the centuries, and little did I know what a tangled web I would find.

Herne the Hunter is a mushroomy sort of character, in many ways: there if you look, but rarely centre stage in a woodland diorama. For me, as for many writers and readers I’ve spoken to, he had lurked on the edge of my field of folklore-vision for a long time, popping up in stories that belonged to other characters. There he is in John Masefield’s The Box of Delights, playing the wise mentor to Kay Harker. Then again in Susan Cooper’s The Dark is Rising, menacing Will Stanton with his owl eyes. He crops up in Nick Hayes’s The Book of Trespass, as the author contemplates breaking the law to touch Herne’s Oak. He got his moment, perhaps most famously, in Shakespeare’s The Merry Wives of Windsor, and received a glorious origin story in William Harrison Ainsworth’s 1842 novel, Windsor Castle. If Herne were a mushroom in the folkloric forest, perhaps he’d be the fly agaric: arresting when spotted, gorgeous and dangerous, courting the human footways but rarely sought to fill a whole foraging basket.

When I dug beneath my fly agaric, strange things began to happen. Searches through books, journals and the internet led me from Herne to Odin, as I expected: both mythic forces who hanged themselves from sacred trees; both leaders of the Wild Hunt. But after that the mycelial network proliferated, and revealed its own interweavings, around or through Herne. I found not just dozens of Wild Hunt leaders, from King Herla to Gwynn ap Nudd, but characters that had carved out their own ecosystems of lore. Harlequin turned up in his diamond-patterned finery; the Erl-king loomed from the shadows; the Green Man gave a leafy grin. Here were not only psychopomps and cursed ghosts but entertainers, mischief-makers, spirits of the wood and of bacchanal. Each time I tried to separate out a thread and follow it, I’d find myself digging into Fairyland here, Tudor history there, or Roman mythology somewhere else. Oberon, Robin Goodfellow, the Woodwose and the Lord of Misrule emerged laughing from the earth. The familia herlechini was widespread, but it was also unruly.

Perhaps the ultimate horned god is Cernunnos who, like Herne, has a special place in much contemporary pagan and Wiccan practice. Surely, at the centre of this wood-wide web, I would find him, mycelial threads knotted about his horns? But such a simple solution did not feel compatible with Herne and his family of rascally, woodsy hunters and seducers. It was not just that all of mythic symbolism seemed to be here: life, death, freedom, lust, wildness, and mischief. What struck me was the sheer range of form and territory. Herne’s multitudinous counterparts are spread far and wide. King Herla rode through the Herefordshire sky; Harlequin took to the stage as Arlecchino in Italy and beyond. Their wildness and mischief seemed to erupt wherever and whenever people needed it.

It was this sprawling mycorrhizal network across space and time, the secret source of so many sprouting tales just where and when we needed them, that gave me permission for another bit of digging: I took my trowel to Herne and transplanted him from his traditional Windsor haunt to the Great North Wood.

Remaining fragments of this huge forest scatter South London, the best known being Sydenham & Dulwich Woods. I was living across the road from this slender, seductive strip of woodland when I began writing Mischief Acts. I knew people had lived in it, from the charcoal burners and famous gypsies of long ago to eccentric hermits and, most recently, a man named Solomon who still managed to receive letters via the Royal Mail by hanging an old house number from a tree. The wood, whether big or small, seemed always to have had a genius loci, or protective spirit. If I – and maybe others – now needed Herne the Hunter in our urban wood, would he come along for the ride?

There’s a tension here, for me: folklore is so often rooted in place, and I feel strongly that local lore can reconnect us with landscapes, even re-enchant us. But I also believe that the need for mischief, transgression, wildness in landscape and soul, is universal, and to me this is what Herne the Hunter – along with his many likenesses – represents. So, it didn’t feel strange, in the end, to borrow Herne and ask him to defend the wood I loved as if it were his own. He’s the wildman, the spirit of the forest, the hooligan and the trickster, and wherever civilisation lapses, as it does where the town gives way to the wood, we will find him.

Fiction has always played a role in extending and morphing folklore, even as lore feeds fiction. For this reason I suspect that, as with the real mycorrhizal network beneath our feet, we will never discover the edges of Herne the Hunter’s folkloric web. Not far from the fly agaric, velvet shank and amethyst deceivers wait quietly; beech mast sprouts into new saplings and wood anemones expand their territory. The forest of stories forever renews itself, in beautiful symbiosis with the web of folklore beneath it.

Mischief Acts by Zoe Gilbert

‘Herne the hunter, mischief-maker, spirit of the forest, leader of the wild hunt, hurtles through the centuries pursued by his creator.

A shapeshifter, Herne dons many guises as he slips and ripples through time – at candlelit Twelfth Night revels, at the spectacular burning of the Crystal Palace, at an acid-laced Sixties party. Wherever he goes, transgression, debauch and enchantment always follow in his wake.

But as the forest is increasingly encroached upon by urban sprawl and gentrification, and the world slides into crisis, Herne must find a way to survive – or exact his revenge.

With its intoxicating, chameleonic voice and boundless imagination, Mischief Acts is British folklore as you’ve never read it before: dangerous, sexy, troubling, daring, savage, an exhilarating race through time and space, weaving together the ancient and the contemporary.‘

Mischief Acts, by Zoe Gilbert, is available from Bloomsbury books.

The book can be purchased here.

Folk by Zoe Gilbert

‘The remote island village of Neverness is a world far from our time and place.

The air hangs rich with the coconut-scent of gorse and the salty bite of the sea. Harsh winds scour the rocky coastline. The villagers’ lives are inseparable from nature and its enchantments.

Verlyn Webbe, born with a wing for an arm, unfurls his feathers in defiance of past shame; Plum is snatched by a water bull and dragged to his lair; little Crab Skerry takes his first run through the gorse-maze; Madden sleepwalks through violent storms, haunted by horses and her father’s wishes.

As the tales of this island community interweave over the course of a generation, their earthy desires, resentments, idle gossip and painful losses create a staggeringly original world. Crackling with echoes of ancient folklore, but entirely, wonderfully, her own, Zoe Gilbert’s Folk is a dark, beautiful and intoxicating debut.’

Folk, by Zoe Gilbert, is available from Bloomsbury books, or as a special edition with sprayed edges from Goldsboro books.

The book can be purchased here.