Fairy tales, myths and legends have always been central to our experience as human beings. They help us deal with difficult, complex and even taboo subjects, turning our inner struggles into fights with dragons or escapes from castles.

We should all be able to recognise ourselves in fairy tales. But what happens when you belong to an invisible minority? Recent years have seen an upsurge in feminist fairy tales. There are now books of gay fairy tales. I even won a prize myself for a gender-swap fairy tale. But what of asexual fairy tales?

It is fair to say that most people have never heard of asexuality. The biggest problem asexuals face in coming out is not persecution but erasure. People have been told to their faces that asexuality is a myth, or asked if they are plants. Attempts to come out to friends have been met with bafflement or the assumption that it is an intimate marital matter, not to be discussed in public. Asexuals have been told by professionals that they have a medical problem and sent to therapy they do not need.

AVEN (the Asexual Visibility and Education Network) defines an asexual person as one who does not experience sexual attraction. This term embraces a whole spectrum of different identities and represents around 1% of the population.

In contemporary culture, it often seems there is little or no representation of asexuals and our perspectives. People still make jokes about 40-year-old virgins. Advertisers try to sell everything using sex. Our ancestors, on the other hand, seemed much more honest and open about the spectrum of human sexuality. There are many fairy tales and myths that apparently contain asexual characters, or use motifs that speak to asexual issues and struggles.

I was a late bloomer as far as identity is concerned. I didn’t identify as asexual until my late 30s; I didn’t have the words. In the early 90s, when I left school, no one was talking about asexuality. No one was there to help me understand who and what I was. It felt like an unfair taboo.

But I had Ovid’s Metamorphoses. I could read about Daphne, who turned into a tree to escape the amorous advances of the god, Apollo. I could meet Pygmalion, who fell in love with a beautiful, chaste statue. There was something in these stories that spoke to me.

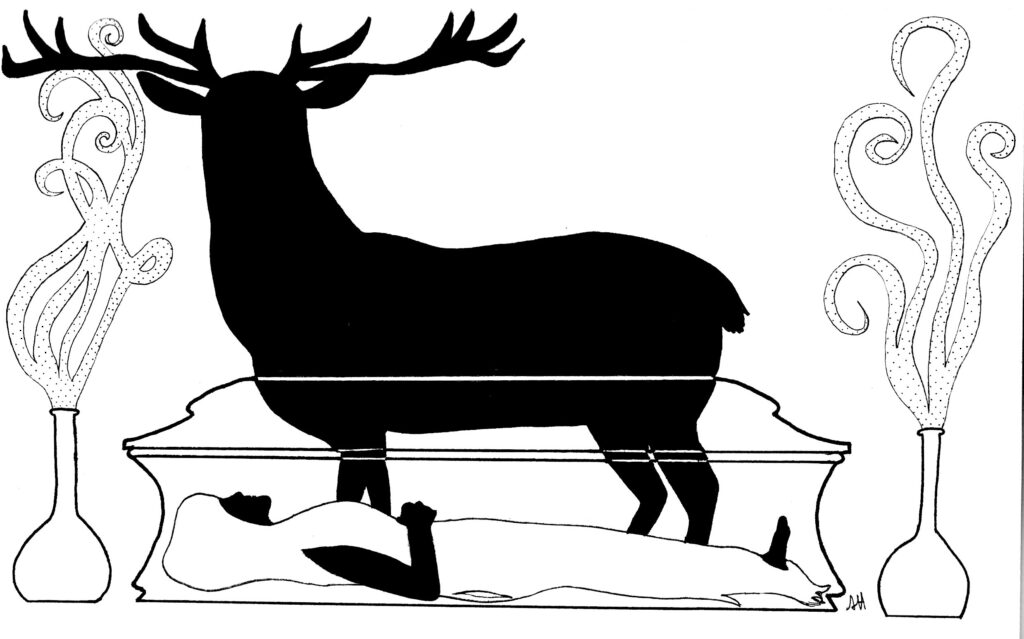

Take, for example, “The Glass Coffin” from the 1853 edition of Grimm’s Household Stories. In it, a tailor is sent on a quest to an underground hall, where a young woman lies in a glass coffin, waiting to be disenchanted. She originally lives happily with her brother, until a suitor arrives, who refuses to take no for an answer. He renders her immobile with enchanted music, and when she still resists, puts her in the glass coffin, transforming her brother to a goat (or hound, or stag, depending on the version), her castle to a miniature in a glass case, and her servants to coloured smokes or liquids in glass bottles. Only when the enchantment is destroyed can she be freed.

There is something deeply asexual about the imagery. The girl in her glass coffin, inviolate. Her helplessness in the face of the immobilising music, tempered with determination to resist at all costs. The desire to live always with her brother, in a kind of sexless marriage. Similar motifs of enchantment, helplessness and immobility appear in this tale’s gender-reversed twin, “The Half-Marble Prince” from 1001 Nights.

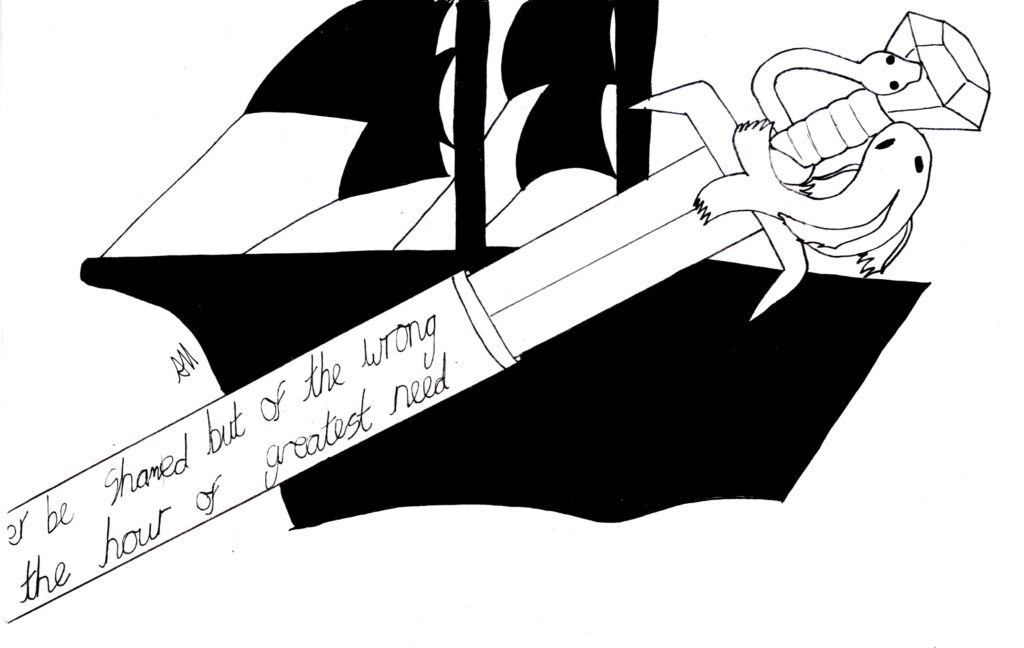

Or take “The Tale of the Sangreal” from Sir Thomas Mallory’s Le Morte D’Arthur (1485). To me, Sir Galahad has always come across as asexual. By contrast with his companions (Perceval is a virgin, while Bors has given up sex for the quest) he never struggles with sexual temptation. It is never even presented to him as a test of virtue, as if the author knows it would be an irrelevance to him.

Among the fellowship of four that will achieve the quest of the Holy Grail, the other asexual seems to be Sir Perceval’s sister (Mallory doesn’t give her a name, so in my retelling I call her Pearl). During the quest, Galahad and Pearl develop what could be read as a chaste romance, an early example of an asexual partnership. Thus in a brief tale, the difference between asexuality, virginity and chastity is perfectly illustrated.

In compiling my own collection of Asexual Fairy Tales (which includes three original tales, previously published in small magazines and anthologies) I have noticed certain motifs recurring. Glass coffins, enchanted sleeps, women in towers, marble statues, mirrors, pearls. This is the language in which I first learned to express my identity. My own, personal brand of romantic asexuality idealises inviolate women and androgynous men. My icons are Sir Galahad, the Virgin Mary, the Lady of Shalott and the 18th-century castrati singers.

This is where I recognise myself in fairy tales, myths and legends. I hope that, in putting them to paper, I will help break the taboo and add to asexual representation. Asexuality covers a broad spectrum, and I’m aware that the tales in my book won’t relate to everyone’s experience. But these are the stories that helped me. I hope they will help someone else.

An extract from The Glass Coffin:

That night, I lay awake on my bed, wishing the Stranger back on the road and everything returned to normal. Suddenly, I became aware of music playing, a sad and beautiful melody that conjured up the most bittersweet memories of lost childhood and golden days gone forever. I could not think from where the music came; it sounded nothing like our harpsichord or my brother’s flute. I tried to get up from my bed, but to my horror, an invisible weight pressed down on my chest. It felt as though someone had laid rocks on me. Then the Stranger entered.

He was pitiable no longer. Striding through doors I had presumed locked, he loomed over my bedside. His high forehead and Grecian nose stood out in profile as shadows on the wall. His eyes were as black marbles.

“Ah, my dear.” His voice purred. “You must know how I have desired you. And now you have been seduced by my music and my enchantments, there is nothing to stand in my way. Your brother believes us betrothed already.” He laid a hand on the pillow.

I stiffened, willing my whole body to turn to stone.

“You shall never seduce nor take me,” I said. “Nor shall any man.” And I raised my voice. “Brother! Brother! Come quickly and help me!”

The Stranger gave a hiss of annoyance.

“You will regret this,” he said. “There is more than one way to possess you. And you will find your brother less able to aid you once I have dealt with him.”

The moment he left the room and the enchantment ceased, I leapt from the bed and pushed two chairs against the door. Next, I searched under the bed for my father’s old duelling pistols. I took them from the box, loaded them and placed them on the bedside table. I then fell into an uneasy sleep.

References & Further Reading

Burton, Sir Richard, The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night (1885)

Grimm, J & W, Household Stories (George Routledge & Sons, 1853)

Mallory, Sir Thomas, Works, ed. Eugene Vinaver (Oxford: OUP, 1971)

Ovid, Metamorphoses, trans. David Raeburn (London: Penguin, 2004)