Four gray walls and four gray towers,

Overlook a space of flowers,

And the silent isle imbowers

The Lady of Shalott.

These words have thrilled me ever since I was a sixth-former. For me, the Woman in the Tower speaks into my experience of shyness, social anxiety and the “invisible bubble” that separates you from the world during periods of intense depression. It is also a positive symbol of the Inviolate Female, of virginity, chastity and asexuality.

Yet I know that, for many, the Woman in the Tower is a symbol of female oppression and repression, a highly negative image charged with a history of daughters denied their freedom. So, let’s take a look at some Women in Tower stories from different times and places, and see what symbolism we can find within them.

Lock Up Your Daughters

Let’s begin with Aarne-Thompson-Uther Type 310, or as it is better known, “Rapunzel”.

One of the earliest recorded versions comes from Persian epic The Shahaname written by poet Ferdowsi (940-1020AD) who collected his material from pre-Islamic stories. Hero Zal and heroine Rudabeh fall in love with each other from afar on the basis of descriptions. Zal is a white-haired youth raised by the phoenix-like Simorgh. Rudabeh is descended from the evil serpent King Zahhak. Yet despite their misgivings about each other’s ancestry, they agree to meet. Rudabeh offers her hair for Zal to climb up to her tower, but he brings a rope instead, as he doesn’t wish to hurt her. They vow eternal love, and their marriage heals family hurts. This seems a rather even-handed tale, reflective of a society in which women and men lead distinct, separate lives, and marriages bring warring families together.

By the time the tale reaches Europe, heroes no longer care about hurting their girlfriend’s scalp. The image of climbing up the hair is too good to resist. Giambattista Basile’s “Petrosinella” from Pentamerone (The Tale of Tales) published in Naples, 1634 and 1636, introduces the theft from the witch’s (or ogress’s) garden and the promise to surrender the newborn child. The ogress takes Petrosinella at age seven and puts her in a tower. A prince climbs up, the local gossip gives the game away, the lovers make a rope ladder and run away with some enchanted nuts with which to see off the ogress in her pursuit.

In the Grimms’ retellings, the fairy/witch takes Rapunzel at age 12. This seems to connect the tower more strongly with the parent’s wish to lock up their adolescent daughters to stop them having sex with boys (or indeed girls). It is both a desire to protect against abuse and an unwillingness to let go of the child your daughter has been. Of course it backfires. A prince climbs in and Rapunzel gets pregnant. (At least in the 1812 version, she does. The tale has been toned down by the child-friendly 1857 version). Rapunzel is cast out. The prince is thrown from the window and blinded by thorns. It is up to the lovers to find each other again.

Interestingly, in these two versions it is a mother figure who locks Rapunzel in the tower. In the Filipino “Juan and Clotilde” it is an evil (male) magician who dies frustrated by Clotilde’s refusal of his advances and curses her into the tower. (Along with three magic horses). Her rescuer is not a prince but the peasant Juan, who sensibly brings a hammer and nails and some rope. Unfortunately, someone pulls the nails out, so they have to escape on one of the magical horses. (Why didn’t she do that before?) Symbolically, this has echoes of “The Glass Coffin” and points to a more proprietorial, masculine motivation for the tower.

There is also the unrelated story of “Jungfrau Maleen” (Grimm) adapted by Shannon Hale as The Book of a Thousand Days. The girl in this tale is bricked up in a windowless tower (with her maid) by her father because she wants to marry one prince and he wants her to marry another. The prince sometimes comes and shouts through the gaps, but eventually the two girls tunnel out by themselves. The maid then pretends to be the mistress, and we go into the “spot the true heroine” motif.

The Bird-Man

There is an interesting subset of Women in Tower stories in which the lover comes through the window in the form of a bird.

One such is the Breton Lai “Yonec” written down by Marie de France in the twelfth century. The lady here is placed in a tower by her jealous, older husband, although there is a mother figure in the form of an old widow sent to guard her. A hawk flies through her window and turns into a knight, who has loved her from afar, like Zal. The old woman discovers their affair and tells the husband, who has iron spikes put on the window. The hawk flies into the spikes and is mortally wounded. The lady jumps twenty feet through the window to follow the trail of blood to a magical city where her lover lies dying. She swears her unborn child will avenge his father.

In Danish fairy tale “The Green Knight” retold by Svendt Gruntvig in 1919, the bird-man appears when the heroine reads from a magical book he has sent her. The book also makes her attendants fall asleep so no one sees them, but the girl’s suspicious stepmother plants a pair of poisoned scissors on the window, with similar results as in “Yonec”. It takes this heroine much longer before she goes looking for her love, but they are eventually reunited.

The thorns of “Rapunzel”, the iron spikes and the poisoned scissors are all similarly sharp and vicious. Maybe they point to a desire on the guardian’s behalf to castrate the man who has been intimate with their daughter/wife. Only the Green Knight seems lightly injured. (Interestingly, there is no evidence of pregnancy in this tale). Yonec’s father dies and Rapunzel’s prince is blinded, later restored to sight by her tears.

In fourteenth-century French romance Perceforest, Zellandine (a prototype of Sleeping Beauty) is visited by her lover Troylus who flies through the window of her tower on the back of a godlike man-bird. Interestingly, we are told this is the Window of the Gods through which no mortal can enter. So, Zellandine’s family initially assume her lover is the god Mars. Although this is not the case, the gods have clearly had a hand in their union and in Zellandine’s subsequent pregnancy.

Child of the Prophecy

We are approaching the point where fairy tale crosses into myth. The image of the bird-man hints at something shamanic. When our tales begin to speak of gods, fate and prophecies of vengeance, then we are looking at much older, deeper, elemental meanings.

Fomorian king, Balor, hears a Druidic prophecy that he will be slain by his grandson. So he imprisons his only child, Ethlin, in a tower of glass, guarded by twelve matrons. Cian, from Balor’s sworn enemies the Danaans, disguised himself as a woman and enters the tower by means of a Druidess’s magic. The child born to Ethlin — Lugh — does indeed kill Balor and restores Danaan supremacy. In this case, the lovers of the tower have not brought healing to a family like Zal and Rudabeh, but continued a feud. Actually, Zal and Rudabeh’s son Rostam is, like Lugh, a miracle child and godlike hero.

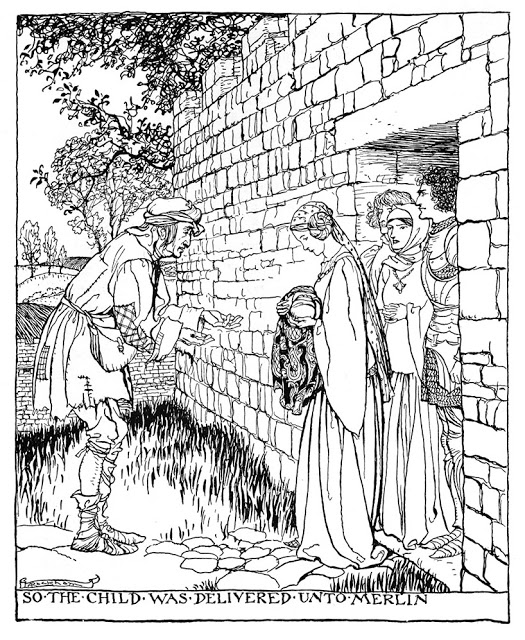

The pattern of the miracle child conceived in a tower occurs twice in the Arthurian legend. King Arthur himself is conceived when Uther Pendragon is spirited into Tintagel Castle by Merlin, to make love to the fair Igrayne in the guise of her husband. Merlin bargains with Uther that in return for his services, he will have the fostering of the child. We’re back to Rapunzel and the witch. Only, instead of a stolen child, we’re seeing a culture in which it was normal for noble children to be fostered outside their parents’ home.

Sir Galahad — foretold as the greatest knight of the world — is conceived when Sir Lancelot is tricked by her father into sleeping with the grail maiden Elaine, who he has rescued from a tower where she was being boiled naked. Elaine is magically disguised as Lancelot’s beloved Queen Guinevere, thus tricking him. Galahad — who is fostered in a convent — does not kill his father, but he does surpass him as the greatest knight and achiever of the quest of the Holy Grail.

There is much more that could be said. In a small selection of tales, we have seen a variety of motifs and meanings for the Woman in the Tower. From overprotective parents to miracle conceptions, from jealous husbands to fertility myths. Far from being confining, the Tower is the fairy tale motif that just keeps on expanding.

Win a copy of Asexual Fairy Tales by Elizabeth Hopkinson

This October we have a copy of Elizabeth Hopkinson’s excellent new book for one lucky newsletter subscriber this month, with one also going to one of our Patreon supporters!*

Almost everyone knows the familiar fairy tale ending: the prince marries the princess and they live happily ever after. Or do they?

Once upon a time, our ancestors were much more honest and open about the spectrum of human sexuality. Among the fairy tales and myths they told were stories of androgynes, neither male nor female; of women and men who resist sex and marriage for other kinds of love; of chaste romances, miraculous childbirth and bodily transformations. These are the asexual fairy tales you will find in this book.

These tales come from many places: from Grimms’ Fairy Tales to The Thousand and One Nights, from Greek mythology and Arthurian legend to the silent films of the 1920s and from Scandinavia to Japan. Retold, reimagined, and sometimes reinvented as new stories for the 21st century, these stories will change the way you think about fairy tales, and bring asexuality out of the closet.

*Sign up for the #FolkloreThursday newsletter to enter our competitions this month

(valid October 2019; UK & ROI only).

Do become a #FolkloreThursday Patreon supporter

for an extra chance to receive copies of the latest books and folklore goodies!

References and Further Reading

Adverse Camber. The Middle Yard. Programme notes, no date.

Cox, Susan McNeill. The Complete Tale of Troylus and Zellandine from the “Perceforest” Novel: An English Translation, from Merveilles & contes Vol. 4 No. 1 (May 1990). JSTOR: Wayne State University Press, 2015.

Grimm, J & W. Household Stories. London: George Routledge & Sons, 1853.

Gruntvig, Svendt. Danish Fairy Tales, trans. J Grant Cramer. Boston: Four Seas Company, 1919.

Malory, Sir Thomas. Works, ed. Eugène Vinaver. Oxford: OUP, 1971.

Marie de France. The Lais of Marie de France, trans. Glyn S Burgess & Keith Busby. London: Penguin, 1986.

Matthews, John. The Arthurian Tradition. Shaftesbury: Element, 1994

Rolleston, T W, Celtic Myths and Legends. London: Senate, 1994.

Tennyson, Lord Alfred. “The Lady of Shalott”. 1833. The Oxford Book of Story Poems, ed. Michael Harrison & Christopher Stuart-Clark. Oxford: OUP, 1995.

Online Sources of Rapunzel Stories

Ashliman, D L. Folktexts: A Library of Folktales, Folklore, Fairy Tales and Mythology. 2008-2015.

Campbell, Jen. Fairy Tales with Jen. 2016-2019.

Heiner, Heidi Anne. SurLaLune Fairy Tales 1998-2016.

Zal and Rudabeh (The Shahname)

Retellings

Forsyth, Kate. Bitter Greens. London: Allison & Busby, 2012.

Hale, Shannon. The Book of a Thousand Days. London: Bloomsbury, 2008.

Marillier, Juliet. Tower of Thorns. New York: Penguin Random House, 2015.