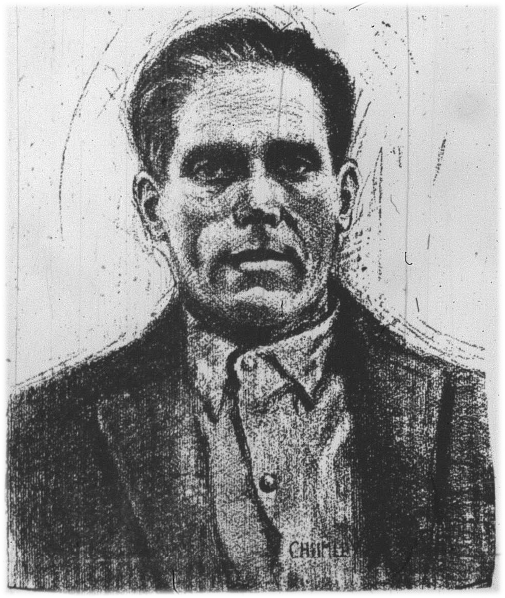

“Fire!” Joe Hill gave the command himself. And the firing squad did just that, executing Hill on November 19, 1915, and creating a labor martyr.

Born Joel Emmanuel Hägglund in 1879, the man known to history as Joe Hill emigrated with his older brother in 1902 to the United States. Their mother had died earlier that year; their father in 1879. Hill, who was also known for a time as Joseph Hillstrom, travelled the United States as an itinerant worker, spending time in New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Illinois, North Dakota, South Dakota, Washington, Oregon, California, Mexico, and possibly Alaska and Hawaii. Though his biography in these early American years is murky, there’s some evidence to suggest he fought in the Mexican Revolution in 1911. But where he worked, what he did, who he knew? That’s harder to pin down. What is clear is that Hill became a Wobbly—a card-carrying member of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), an industrial union founded in 1905. As an IWW member, he wrote songs about and for the working class, and continued to do so while imprisoned for a murder that many believe he did not commit. In the decades to follow, his case has been investigated again and again by historians and journalists, most recently in 2015 for the 100-year anniversary of his death. While people still debate whether Utah executed an innocent man or not, his songs continue to be sung.

These songs, political in nature then and political in nature still today, are part of the branch of folklore studies known as occupational folklore, or laborlore. Archie Green, who coined the term laborlore, wrote extensively about the traditions that workers circulate among themselves—like jokes or songs or stories, cartoons or essays or letters—and how those traditions are circulated among other workers and sometimes passed down from one generation to another. Green argued that laborlore, whether exchanged orally or in written form, is critical to folklore studies because it works to include the voices of people who’ve been forgotten or ignored. People who don’t always make the history books. People like the itinerant workers and immigrants who made up the rank and file of the IWW. People like Joe Hill.

Hill is perhaps most famous to modern readers for a song he did not write, but instead was written about him. Alfred Hayes and Earl Robinson’s song “Joe Hill”—Joan Baez, Paul Robeson, and Pete Seeger—is meant as a reminder that the spirit of the labor movement cannot be killed, and as a call to action directed at workers and union members to organise for their rights.

But Hill wrote his own songs. Exactly how many is hard to say, since plenty of IWW songs were sung without attribution by workers around the country at lumber camps, on factory floors, and at strikes. Still there are many that we know Hill wrote, like “The Preacher and the Slave,” “There is Power in a Union,” and “The Rebel Girl.” The first two are set to Christian hymn tunes, which served a couple of different purposes. Firstly, they were easy to remember. Plenty of folks had a Christian upbringing. Plenty of folks had spent a bunch of Sundays in church. Plenty of folks knew the melodies. Put some new words to the music, and it was a lot easier to remember. That wasn’t the only reason Hill and other labor activists borrowed religious melodies – putting new words to Christian hymns was a political statement as well. Hill’s songs call for workers to organise, to take power from the ruling class, and to recognise the class inequalities that Hill and so many others lived. Songs like “The Preacher and the Slave” were sung to point out the hypocrisy that the IWW saw in organisations like the Salvation Army – sometimes referred to as the “Starvation Army” – that asked workers to trust in God and to accept their earthly plight, no matter how bad.

You will eat, bye and bye.

In that glorious land above the sky;

Work and pray, live on hay,

You’ll get pie in the sky when you die.

Despite being a Swedish immigrant, Hill wrote in English. In fact, it doesn’t seem like he wrote at all in Swedish. Others, like Signe Aurell, did. Chances are you’ve never heard of Signe Aurell. She moved to the United States in 1913 at the age of 24, settling in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and returned to Sweden in 1920. While in the US, she worked as a laundress, a seamstress, and a domestic servant. Aurell’s work appeared in at least seven different Swedish-American newspapers and two Swedish newspapers in the form of poems, short stories, essays, and a translation of “Joe Hill’s Last Will,” written by Hill in prison before his execution. As a Wobbly, Aurell lent a Swedish voice to the IWW, which actively recruited immigrant workers. Her work spoke to a different audience, reaching out to the people who had come to the New World but did not speak English. As with her “Last Will” translation, Aurell sometimes drew inspiration from Hill. Several of Aurell’s poems appeared in the Swedish version of the IWW songbook, including one published in Seattle, Washington, around 1930, fifteen years after Hill’s execution and ten years after Aurell had left the country. The poem memorialises Hill in his fight against the ruling class. I’ve included an excerpt (with my own translation) below:

Josef Hillströms död

Så föll han för kulornas mördande stål

I kampen mot våldet till slut

De rika, de stora ha hunnit sitt mål

Och segrat som alltid förut.

Om liv eller frihet han tiggde dem ej,

Han fordrade rättvisa blott,

Och svaret var domarens stenhårda Nej!

Och bössornas dödande skott.Josef Hillström’s Death

He fell to the cold bullet’s murderous steel

Fighting violence until the end

The rich, the powerful, they’ve made their deal,

They’ve always won, they do not bend.

He did not beg for his life nor for freedom,

But demanded only justice,

A stone-cold no from the judge’s mouth did come

Along with the rifle’s cruel kiss.

Of course, not all laborlore is song and poetry. I don’t spend much time singing at work. Maybe you don’t either. But the stories we tell, the songs we (or other people) sing, the jokes we recite – they matter as a form of laborlore. They help us to assign meaning to what we do, and to take charge of our identity. We crack jokes about our workplace to get through the day, we exchange memes that only our co – workers understand, we slap stickers on our laptops that read “Folklore Rules.” We do this sometimes as an act of defiance – as Joe Hill and Signe Aurell might have done – and sometimes as a display of our identity. But we do this.

So next week, when you’re at work, look around. Pay attention to the little things that go on that make your job and your workplace unique. Pay attention to how you and your co-workers express your identity. Pay attention to the laborlore you pass on, the laborlore you create, the laborlore you’re a part of. Laborlore, like poems and songs by Joe Hill and Signe Aurell, allows us to delve into the history of our country through the eyes of the men and women who built it and to potentially better understand the intersections of work and immigration that are in the news so much today.

Recommended Music & Books from #FolkloreThursday

References & Recommended Reading

Eds. Archie Green, David Roediger, Franklin Rosemont, Salvatore Salerno, and Utah Philips, The Big Red Songbook: 250-Plus IWW Songs. Chicago: Charles H. Kerr Publishing Co., 2007.

Green, Archie, Torching the Fink Books and Other Essays on Vernacular Culture. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001.

Green, Archie. Wobblies, Pile Butts, and Other Heroes: Laborlore Explorations. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1993.

Rosemont, Franklin. Joe Hill: The IWW & the Making of a Revolutionary Workingclass Counterculture. Chicago: Charles H. Kerr Publishing Co., 2003.

Anywhere But Utah: The Songs of Joe Hill http://amzn.to/2n7VTTE

Calf’s Head and Union Tales: Labor Yarns at Work and Play http://amzn.to/2nnzP9M

Talking Trauma: A Candid Look at Paramedics Through Their Tradition of Storytelling http://amzn.to/2n8cYwY