“Hat, cat, rat,” Umakant would shout at the top of his voice whenever he would see cowherds around the Peepal tree. Umakant had recently joined our village school as a teacher of English. Called Uma Babu by villagers and English Master Saheb by his pupils, he conducted classes in the shade of the giant Peepal tree.

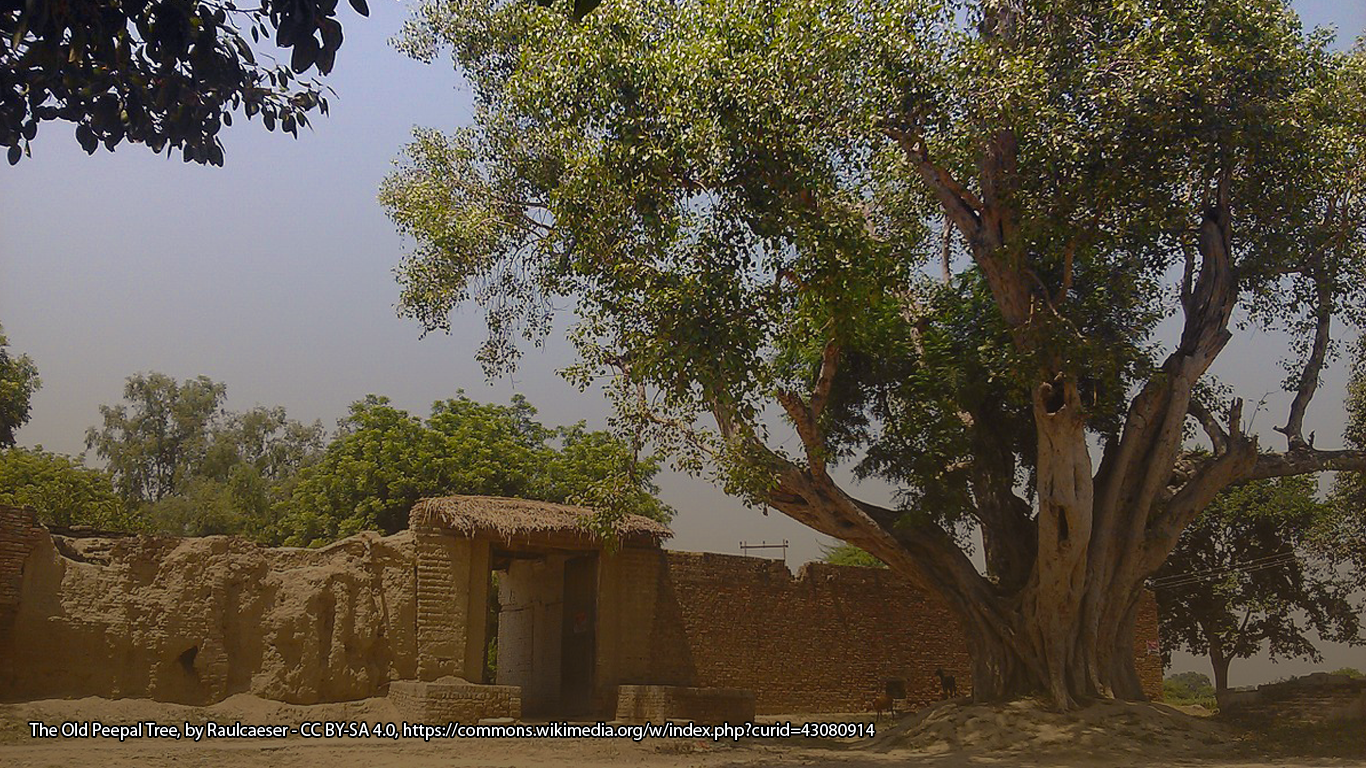

The old school building had caved in long ago. Thick bushes of grass and brambles had grown on the uneven mound of its ruins, some 50 metres away from the Peepal tree, which served as a grazing land for cows, buffaloes and goats. The school was surrounded by patches of lush green grass and crops of wheat, peas, gram and mustard flowers. The Peepal tree canopied about 800 square metres of the earth. Its round leaves clattered and sang in symphony with the chirping of sparrows which populated the nests in its dense branches. The livestock grazed in the grass fields nearby and the cowherds — in bare torso and similar pieces of soiled cloth tied around their waists — sat on their haunches under the tree. The fenceless school campus had an old well into which the cowherds would suspend a tumbler through a string and draw water to drink.

The teacher and the students would sit on empty jute sacks. The students, numbering 20 to 25, would usually sit in three to four rows. Umakant sat separately, facing his pupils. The atmosphere used to be relatively calm, with the students drawing some pictures with chalk on their wooden slates, and Umakant calling them one by one to examine their work.

Umakant would suddenly scream “hat, cat, rat” repeatedly on seeing the cowherds. The cowherds, sturdy batons of bamboo in their hands, would lend their ears to him even though the three words were alien to them. “Umakant is a scholar of English. He speaks in English. Thank God, he has joined our village school. Our boys will learn English now,” once murmured a cowherd, adjusting grip over his baton. Another cowherd added, “You are right. We never got a teacher to teach us English. But our boys have got. God is so kind to us.” The cowherds would leave their batons aside and get close to Umakant with folded hands, praising him for his ‘command’ of English and expressing gratitude for teaching their sons.

But Umakant would politely say, “Please don’t waste my valuable time. You better leave when I am teaching the students. I will talk to you after the class is over.” Umakant’s reluctance to indulge in gossiping at school time enhanced his image among the cowherds. “He is a saintly teacher, a God-like figure for our boys. We should not disturb him,” the elderly cowherd would say and herd away the others.

While the students scribbled on their slates, Umakant would take a nap and even snore. And he would scream at the students when they talked loudly and disturbed his sleep.

The cowherds talked endlessly about Umakant’s pedagogical skills. Apart from their cattle and crops, the villagers talked only about Umakant’s knowledge. “Umakant cried in English when he was born,” said a cowherd. Another intervened, “No, no! He never wept. He laughed in English when he was born.” Yet another added, “He was an Englishman in his previous birth.”

Though Umakant was one of the three teachers at the school, he was the only one who was talked about. The villagers had woven many stories about Umakant, who was in his 50s when he joined the village school. The villagers treated the two other teachers, Pancha and Giriraj, as ‘good for nothing’. The duo belonged to a neighbouring village and did not know English. They taught Hindi and numerics. They were farmers who usually carried out agricultural chores and used to drop in the school to mark their attendance only occasionally.

But Umakant was special. Unlike Giriraj and Pancha, he lived at Siwan, a town about 35km from the school at our village that was tucked away in a remote corner of Siwan district in the Indian state of Bihar. The village population consisted of about 25 families. They resided in mud houses and huts. Almost every door had few cattle heads. The villagers lived on the cattle and agriculture produce. Umakant would catch a bus at Siwan early in the morning and reach at a stopover where the metalled road ended. From there, he would walk for four kilometres on the zigzag path of mud to reach the school, an umbrella and a walking stick in his hands.

Umakant wore a V-shaped blazer over his kurta and dhoti. It was a grey blazer, old and crumpled. He had two fountain pens clipped in the blazer pocket which had become stained with ink leaks from the pens. The blazer never appeared to have been washed or ironed. It was not known if Umakant had bought it or got it from someone. But it was a blazer, and the villagers had never seen anyone other than Umakant wearing a blazer. Umakant also wore shoes on his sockless feet. He had knotted the shoelaces in such a way that he was not required to untangle them while wearing or removing the shoes. Occasionally, he would wear a hat to look like a special teacher. The villagers wore headgear, and they had the impression that only the British sahibs used to put on hats.

It was early 1970s. The British had left India over two decades ago in 1947. But the villagers thought that a hat and blazer-wearing person carried the virtues of an Englishman. Even the elderly villagers who had been witness to the British rule had not seen the sahibs who had governed India from fortified palaces in big cities and towns. But the villagers had somehow preserved the impression that a clean-shaven and hat-wearing person had the attributes of an Englishman. Umakant also carried a small comb with him and would invariably comb his hair that had turned grey. Ostensibly the only one in the area who would wear a blazer, leather shoes, and hat, he also had a thin line of trimmed moustache on his clean-shaven face. The villagers would get their beard shaved by the local barber only once or twice in a week.

The villagers were largely illiterate. But they didn’t give importance to the people who could read and write only Hindi, and treated such people as ordinary mortals like themselves. They were in awe of Umakant, who could speak English synonyms of the animals and objects around them. They wanted their children to be educated by Umakant, as knowledge of English was the real education for them. Umakant was the only teacher who spoke the words like hat, cat, and rat, and therefore, the villagers held him in high esteem.

I was a student at the village school. My father was also a teacher, albeit in another school in another village. Like other teachers, my father too didn’t know English. Moreover, he was first a farmer, a relatively well-off one, and then a teacher. He was respected because we had a house with a big veranda. We had more farmlands and more cows, buffaloes, and oxen than others. Many poor agriculturists who had small huts that leaked in the rains used to take shelter at our veranda. There was also a small guest room in the corner of our veranda. My father wanted me to learn English and go to the city for higher education.

“Babu! Umakant is a fantastic teacher. He speaks in English,” said one of the cowherds, who had gathered at my home on a Sunday, to my father. Another cowherd proposed, “Umakant is a ‘master teacher’. If you spare your guest room, he can live in the village and give more time to our children.” My father desperately wanted me to learn English, as he was of the firm opinion that it held the key to bag a decent job and become a gentleman. He met Umakant the very next day.

“Pranam (Hindi word for salutation),” my father said, with folded hands, as he walked close to Umakant at the school. Umakant responded back, “Good morning, Master Sahib.” My father was visibly impressed to hear the English salutation. As Umakant got up with folded hands, my father said, “Your manners suggest that you have good knowledge of English.”

Umakant grinned and chanted, “ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ” in one go. My father was visibly excited to hear him chant the English alphabet so speedily and flawlessly. Umakant went on, “these are the 26 letters which contain everything about English. I know how to read and write the small and capital forms of these letters. Besides, I can call animals and birds by their English names.” My father quipped, “It means you know everything about English. You are a good teacher. Stay at my house and take care of my son.” Umakant nodded delightfully. My father took him to our house and showed him the guest room in which he began living.

The cowherds used to bring a tumbler full of milk, flour, and ghee for Umakant. They used to cook litti (rounded dough baked in cow dung fire), soak it in ghee and feed Umakant. Some of them would press his feet to comfort him. Others would sing folk songs to regale him. They did everything to keep him in good humour. My father was also happy that the villagers were taking care of Umakant so well.

Umakant’s lifestyle was distinct. He was used to taking tea and smoking Panama cigarettes. Every Sunday, he would go to Siwan and buy his quota of tea leaves and cigarettes. He would boil his tea in a tumbler on the bonfire that my father lit every morning and evening to keep mosquitoes away. The villagers were not into tea and cigarettes. They would instead gulp down rass (sugarcane juice or jaggery dissolved in water) and smoke bidi. Some of them chewed khaini (unprocessed tobacco). But, you know, Umakant was a teacher of English.

“Uma Babu is not as rustic as us. He knows English,” said a cowherd, basking in the morning sun at our door. My father supplemented, “He has studied in the city schools. He has refined habits. He will inculcate good values in our children.” Sitting on a cot and taking a puff or two few metres away, Umakant would smilingly listen to such conversations, pride writ large on his face.

Umakant had a colourful book that had pictures of animals and birds captioned with their names in English. The first chapter of the book had Roman letters written in small and capital forms. After taking his bath and breakfast at the well in front of our house, Umakant used to wear his dhoti, kurta and blazer and get ready for going to school. But before leaving for the school, he made it a point to copy the Roman letters on another sheet and revise the names of the animals and birds. He would then wear his shoes which squeaked as he walked towards the school, about 200 metres away from our house.

Before leaving for the school, Umakant would sometimes tell my father, “The teachers don’t read these days. They give lots of homework to the students but they themselves never do their homework. I always re-read the books before going to the school.” My father would praise him, “You have all the great virtues. That’s why you are an English teacher.”

Within a short span of time, I became Umakant’s favourite student. Since he lived at my house, he naturally paid special attention to me. He first taught me to recite all the 26 letters of the alphabet. My father had bought me a fountain pen and plenty of sheets. Under the guidance of Master Saheb, I scribbled “ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ”… and “abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz” many times in a day. I was the first to learn to write all the 26 letters in the capital and small forms.

The schoolchildren were supposed to learn English after reaching class VI. For the first five years in the school, we were supposed to learn Hindi in Devnagri script and the number system. Our Hindi textbook had chapters on great people like Mahatma Gandhi, Akbar, Maharana Pratap, some rhymes and essays on cow — the most important animal in a farmer’s family, the rivers, agriculture and agricultural products. The students would turn 10 or 12 by the time they reached class VI. Many dropped out of the school before class VI and, thus, lost the opportunity to learn English for good. Umakant used to teach only class VI and class VII students. Pancha and Giriraj taught in lower classes.

Umakant taught the capital and small letters of the Roman alphabet for the entire year in Class VI. We had to practice writing the letters almost every day. He also taught us the English names of some animals — cat, cow, dog, jackal and monkey. In Class VII, Umakant taught us more words related to household objects like spade and sickle and agricultural tools like plough and ox. He taught us the names of various agricultural produce like wheat, rice, maize, and gram, as well as fruits like mango and guava that grew in plenty on the trees outside our homes or in our orchards. But Umakant would not teach us the names of the various flowers that bloomed in our fields and gardens. He referred to every flower as flower.

Before we left the school for home, English Master Saheb would ask us to mug up the spellings. At the start of the class, he would ask us one by one to get up and spell the words. Those who misspelt used to be caned. I never failed these oral tests.

Most of my friends dropped out after Class VI to help their parents in grazing cattle and doing farm work. I passed Class VII and was admitted to Class VIII at a high school located in another village, about four kilometres away. “Your son is brilliant. His handwriting is also good. He will become a famous scholar one day,” Umakant prophesied to my father while issuing me the School Leaving Certificate. My father was overwhelmed with emotion.

My father bought new clothes for me to wear in the high school. He asked me to touch Umakant’s feet before leaving for high school on Day 1. “You were my best student… You will become a great man one day. May God bless you,” Umakant said. But lo and behold, I was in for a rude shock in my first class of English at the high school. The teacher gave the students three sentences in Hindi and asked them to translate them into English:

- Ram aam khata hai.

- Ram pani peeta hai.

- Ram ko ek gai hai.

These were simple sentences and could have been translated into ‘Ram eats mango,’ ‘Ram drinks water,’ and ‘Ram has a cow.’ But Umakant had not taught me translating sentences. With the help of whatever knowledge Umakant had given me, I attempted to translate the sentences and ended up writing:

- Ram mango.

- Ram water.

- Ram cow.

Surprisingly, the teacher was satisfied and gave me two out of three marks. He said, “Though your translations are wrong, I awarded you two marks because you at least tried to translate all the sentences. Others haven’t.” He also gave me a book of grammar that contained the basic lessons in tense, verbs, articles, syntax, prepositions, and sentence framing. It had lessons in Hindi and English both, and explained the tricks of framing English sentences. Besides, it had many ‘Practice Chapters’ for translation from Hindi to English and vice versa.

As days passed, I realised my ‘command’ of English was quite poor. My high school teacher was very encouraging though. “Practice makes a man perfect” was his oft-repeated one-liner whenever I approached him for guidance. I practised – hard and harder. Days, months and years elapsed. I passed matriculation and went on to study in colleges and universities in cities like Patna, Delhi, and Mumbai. I developed interest in reading Shakespeare, Earnest Hemingway, Charles Dickens, T. S. Elliot, Mark Twain, George Bernard Shaw and other such eminent authors. I was also an avid reader of English newspapers and journals.

After three decades since I left my village school, I had become a journalist writing for English language newspapers and journals in India and abroad. I also became somewhat famous as I churned out some real good news stories and developed acquaintances with several political heavyweights and bureaucrats. Many of them would praise me to my face but loathe me in private. For I never hesitated writing against even my ‘acquaintances’ if I happened to lay hands on newsworthy material against them.

We entered the 21st century. One fine day, I revisited my village and found that it had changed drastically. The cowherds had disappeared. Concrete houses had replaced the huts and thatched habitations. A decent school building had come up at the place where the massive Peepal tree once stood. The sparrows and crows had disappeared. The well of our school had given way to a hand pump on the new school campus. The village was connected to a concrete road from all sides. The car carrying me reached up to my door. Many of the boys had mobile phones in their hands. The houses had got television sets, electric bulbs, and ceiling fans. The television sets blared Bollywood numbers and news that rent the air.

After settling down at my home, I inquired about Umakant. My school friend Nandji said, “He retired long ago. No one knows much about him because he does not have a mobile phone. We hear that he has turned very old. We have not seen him for years. He lives with his wife in a small house at Siwan.” The very next morning I went to meet Umakant. I found his location, but neighbours told me that they had not seen him for days as he was ailing and was bed-ridden. “He is too weak to even stand up and walk. He does not talk to people,” said one neighbour. I was anxious as I entered his room. It was hard to recognise my English Master Saheb. Wrapped in a soiled quilt, he lay in his bed – almost still. His wife was also very old. She was dropping a spoonful of syrup into his mouth. As he opened his eyes, I touched his quilt-covered feet and said, “Pranam, English Master Sahib! I am Munna, your student. I have become a journalist and I write in English.”

Umakant got instant energy. He jumped out of the cot and gave me a tight hug, tears rolling down his eyes. He ran to a shop and bought sweets which he distributed among all and sundry he came across. “God has given me everything. My life is complete,” he screamed repeatedly. After an hour of celebrations, he fell on his bed exhausted, asking me to cover him with the quilt and press his feet. As I began pressing his feet and tried to talk to him, he breathed fast, convulsed and died. There was a smile on his lips that turned silent forever.