Here Nalin Verma recalls memories of his uncle, from his childhood growing up in Bihar, India.

In memory of my Lala who is no more now.

My Lala used to kill scorpions and burn them in bonfire to get the smoke caress me when I was born. My mother would tell it repeatedly when I was about eight to ten year old.

My Lala and other family members believed that the scorpions’ venom would not work on me ever if I was warmed in the smoke emanating from the bonfire that had scorpions smouldering in it at the time of my birth.

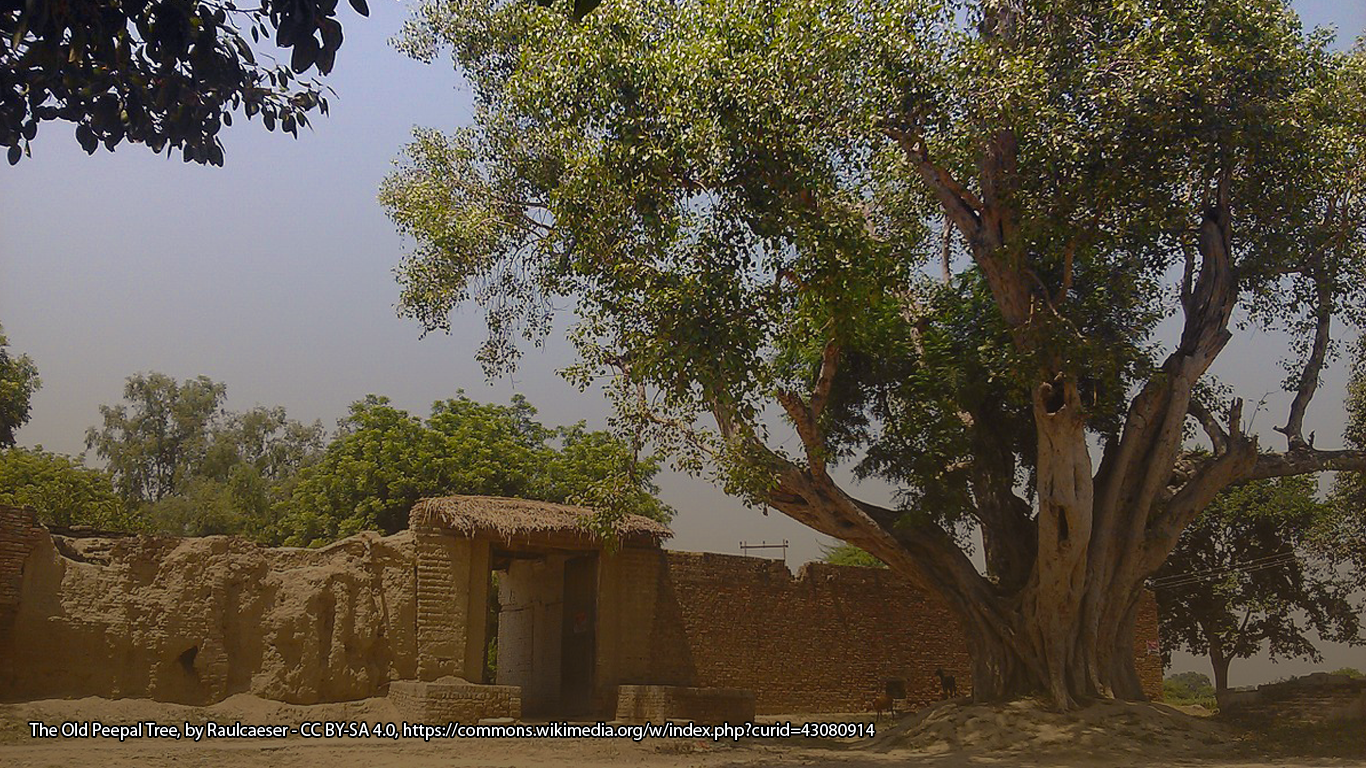

It was in 1960 when I was born at Daraily Mathia, a very remote village in Indian state of Bihar, with cows, calves, buffalos, birds, dogs, jackals, crops, orchards and largely unlettered agriculturists all around.

My loved Lala who was 78 year old when he breathed last on December 9, 2017 at Jamshedpur—a modern industrial city in Jharkhand state of India—where he had settled as a miner 1968.

I too became a journalist, writer and teacher, travelling in many parts of India when I grew old and lost connection with myLala who was so caring to me when I was a just born baby.

The youngest among the father’s brothers were lovingly called Lala—a synonym of uncle—in our village. Raghavendra Prasad Verma nicknamed as Lallu—youngest among six brothers–was my Lala.

My father and three of his brothers had died long ago. My Lala was the fifth among his brothers to die on December 9.

Our elders used to tell me that my birth was a big moment of celebration in the family of poor agriculturists. I was the first child and first member of the next generation in the joint family of six brothers including my father, Late Anant Sharan Verma.

The last to be born among Panchdeo Narayan Lal’s six sons and three daughters was my Lala in 1939. It was a real special moment in the family when I was born in 1960—almost 21 years after the last child (Lala) was born. Birth of a male child after over 20 years of wait was too long in the large family of agriculturists.

My Lala—a young and energetic youth in his 20’s then—was more enthusiastic when I was born. He wanted me to be guarded against the snakes and scorpions that lurked around in our farm fields, bushes, orchards and homes.

Lala’s friend and our neighbour, Phulena Mia was a sorcerer and faith healer who knew the mantra to cure a person from snake bite. My Lala was sure about his friend Phulen’s mantra coming to my rescue in the event of a snake biting me. And he was sure that if I was caressed by smouldering scorpions’ smoke for about three months after I was born I would suffer no pain in the event of a scorpion stinging me ever. So, he had taken it on himself to hunt the scorpions in the farm fields, bushes, heaps of cow dung cakes, woods and brambles and smoulder them in the bonfire to warm me.

When I was a bit older—about a year old—my Lala arranged a madari (a Muslim faqir and bear charmer) to bring a bear at my door and smell my backside. The villagers believed that if a bear smelled the backside of a child the latter would never ever be infected rabies. My father had arranged an elephant for me to ride when I was a year old. The family believed that my ride to elephant’s back would lead me to become a great man later in life.

What I remember is that my mother used to apply kajal (kohl) on my forehead whenever I went out on the streets to play with my mates. It was to ward off the invisible evil spirits and ghosts that were believed to exist in plenty in ponds, wells and orchards at my village.

By the time I acquired the age to remember the things and events, my Lala had migrated to an iron ore minefield in West Singhbhoom district of south Bihar, now Jharkhand, as a miner. But he used to come home in a year or so, bringing sweets, toys and garments for me. He would play football and goli (rounded pieces of glass) with me. He was my best friend whenever he was home. I would cry for days whenever he left home for the minefield, far away. He too had tears full in his eyes while leaving home.

My three brothers—Raju, Tunna and Kunkun—were born in the same ancestral home where my fathers and forefathers were born. We grew playing among cows, calves, buffalos, birds and monkeys, riding the trees, pedalling our old Hercules cycle on the jig jag streets and mud-paths and bathing in our village pond.

We did not know what the hospital and doctors were all about. Whenever we were infected with measles our mother would pray Goddess Kali and rub us with neem leaves. Whenever, we had fever, we were disallowed food till the fever left us. Whenever we caught cold we were given tulsi (basil) leaves boiled in water to drink. And whenever we fell and got wounded, our mother would give warm solution of turmeric and milk to drink that removed our pain.

By the time my two children—Sonali and Saloni—were born, I was a journalist working with prominent national daily newspaper of India and was living in Patna—capital of Indian state of Bihar. Sonali and Saloni were born in posh hospitals of Patna in 1990’s and are attaining higher education at Jawahar Lal Nehru University, New Delhi—a premier institution of India.

In my Lala’s death I see the end of an era at our village which is no longer the same. My village now is connected with roads from all the sides and has electricity supply too. There are hospitals and doctors around. Many youths have mobile phones. Bullocks have disappeared for tractors are there now to plough the fields. There is mushroom growth of schools around our village.

The youths no longer bath in the ponds. No one now believes either in the theory of warming a still born child in scorpion’s smoke or a sorcerer curing the snake bites. The bond between a Lala and his nephew too is a passé now. The families are smaller. They comprise wife, husband and two children at the best.