Let’s take a look at the incredible story of the Benandanti, a surprising third party in the fight of good versus evil in Medieval Italy, that not even the Holy Inquisition could completely make sense of.

When back in the sixties, while cataloguing papers, Carlo Ginzburg stumbled upon an old court record of the Friulan Holy Inquisition, he realized he had made one of those discoveries that careers are built on. Ginzburg, one of Italy’s greatest folklorists, had dedicated half of his life to studying Paganism and local beliefs in the Peninsula. The guy was nowhere near your average fresh-out-of-college student; so you can imagine his surprise when, by chance, he pulled up an interrogation containing the name of a cult he had never heard before.

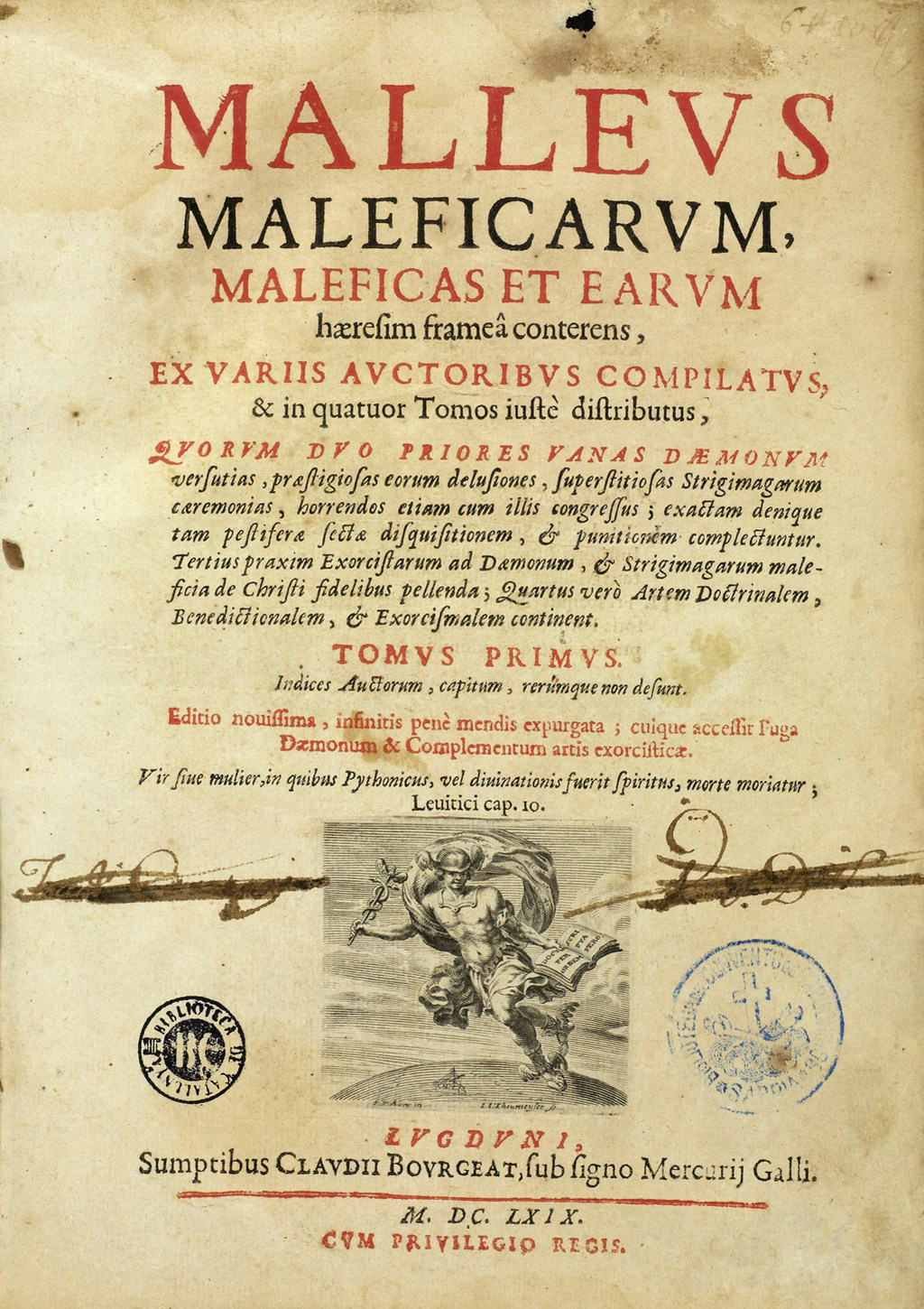

It’s kind of funny how most people associate the Inquisition with the early Middle Ages, and darkness, and ignorance – the institution spans several centuries, and remnants of it survive in the Curie to this very day. Witch hunts, Sabbaths, and all those funny businesses actually started to come up in tribunals around the late Thirteenth century – the age of Dante, since we’re focusing on Italy – and continued in their purest form up until Napoleon re-shuffled all the decks.

Still with me? Well, you’re definitely keener than my student. The idea of witch hunts and the Inquisition as ridiculous superstition – with more than a hint of political and religious persecution – came along during the Enlightenment, as many modern concepts did. The triumph of Reason and Science and Much Capital Letter Stuff came with a healthy dose of skepticism, and the complete disregard of anything confessed in front of an official of the Holy See. “Fabrications,” the wise men said, “superstition and tomfoolery, a disgusting black spot on our greatest Continent.”

Except that they weren’t.

The complete denial of any Pagan and Shamanic tradition in Middle Ages Europe did as much damage to common culture as systematic eradication by the Church did. Faith in God and faith in Science: that was the dichotomy. Those were the only two possible options for what was (and still is!) considered to be the centre of the entire world. Enter the Benandanti.

The date is 21st of March 1575. Father Bartolomeo Sgabarizza of Brazzano is granted reception by a vicar of the Holy Inquisition to discuss a weird occurrence in his diocese. The priest reports that he learned from a miller that there’s a man who proclaims to be able to lift curses, and that he “meanders at night with strigoni et sbilfoni” (sorcerers and elves). The miller was told by this man that he could cure his sick son, as the boy’s illness was supernatural in nature; and so, the priest set out to look for the healer.

(This is a true story – or at least, as true as the official Church papers on it can get. It was reconstructed by scholars, among whom was Ginzburg himself, working on documents from the Archiepiscopal Archive of the Curia of Udine. The Archive contains material spanning across hundreds and hundreds of years, most of it uncatalogued. The labelling and cataloguing of the Church’s records is keeping academics busy to this day. Anyway, back to the narration).

It turned out the man wasn’t even remotely trying to hide his identity. Baffled, Father Bartolomeo summoned him, and the man… well, the man confirmed his story, adding details regarding the nature of the curse and the gatherings he attends regularly, along with other people and several kinds of animals. Brought in front of the Holy Inquisition’s vicar, he not only he kept on professing his Pagan lifestyle, but offered the two to bring them along at the next meeting.

We don’t know whether they accepted or not. What we do know is that – and this is all archived – Father Bartolomeo had come to the conclusion that there is white magic that extends beyond the realms of the Catholic Church – and that the ones practicing it aren’t enemies, but friends. The priest had apparently struck some kind of friendship with the man, inviting him to his house for a few conversations. He learned that the common folk referred to his kind as “Benandanti,” the “Good Walkers,” and that there were quite a significant number of them, all dedicated to fighting against witches.

The next testimony in the papers is from a nobleman, who condemns the whole thing as “folksy rubbish” (his words). As it was a nobleman saying that – of course – the Inquisition dropped the whole case on the spot, but it’s too late. The word Benandanti entered the official records of the Church, and the floodgates were opened.

Inquiries and interrogations would proceed on and off in the following years – mostly conducted in a surprisingly humane and reasoned way, with fascinating debates on sorcery and theology all recorded diligently. The Inquisition, its tribunal interrogating every Benandante it could find, learned three things: One, that the Good Walkers professed to fight “as sorcerers in the name of Christ” against “sorcerers in the name of the Devil”; two, that they were organized like an army, with captains led by a single man who came from Cologne, and sworn to the utmost secrecy; and three, that their main “occupation” is fighting against witches and devils for a bountiful harvest.

Notice I haven’t used the word “Sabbath” yet to describe the Benandanti. In the Inquisition’s world, that’s a word with a very specific legal connotation. Being able to demonstrate the exact occurrence of one would allow them legal ground to do, you know, the whole Inquisition thing. It was an actual legal system, with extremely strict definitions and timings to match – all these events happen in the span of years. But Sabbaths imply adoration of the Devil, and by all accounts the Benandanti did quite the opposite – in their own twisted way, they did what they did in the name of Christ.

Even by “correcting” the documents, the worst that the more rabid side of the tribunal could do was accuse Father Bartolomeo’s friend of haereticalia, which translates to “you guys are doing the Christianity thing wrong and here’s a list of corrections to take care of,” with a side order of a fine and very light prison sentence. But something doesn’t add up.

Where did the whole Christ thing come from? From the sources at hand, it’s clear that the Benandanti are the last remaining vestiges of a former Pagan cult of harvest and forces of nature. In this respect it’s nothing special – the Church had eradicated and/or replaced dozens of those in its evolution, assimilating their practices in the Cult of the Saints. But not even the Inquisition had heard of them before, so… where did Christ come in from?

There are several hypotheses on this, and the most fascinating is that it developed spontaneously as a natural reaction to witchcraft. As people turned to the Church to defend themselves from witches – something that was much hazier before the Inquisition went through the bureaucratic ordeal of defining it precisely – the Benandanti apparently realized they were fighting against people who did the work of Satan. It was only logical that they pledged allegiance to Satan’s greatest adversary.

The story of the Benandanti doesn’t end here (it has barely started) but sadly my word count does. This is just the beginning. Father Bartolomeo’s curiosity ignited a process that the Inquisition would only drop far into the following century, a series of inquiries interlacing with (black) witchcraft and heretical bishops, and a feud that saw them and the witches try to play the Inquisition against each other multiple times.

If you folks would like to hear the stories of the Good Walkers, do let us know and maybe we’ll continue in another article – maybe with a focus on the witches’ side next time. We’re all always on Twitter during #FolkloreThursday, or you can read The Night Battles: Witchcraft and Agrarian Cults in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries and learn the story from the mouth of Carlo Ginzburg and our protagonists themselves.