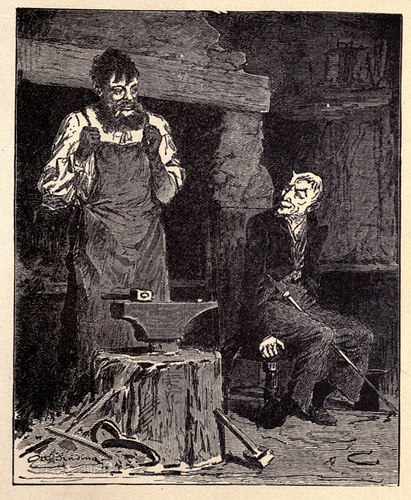

Some fairy tales are older than any of the languages used to tell them… and the oldest ‘folk-tale’ of all seems to be that of a blacksmith forging a deal with the devil.

These findings were made known during 2016 in an article published in the Royal Society Open Science Journal, in which Sara Graça da Silva and Jamshid Tehrani traced population migrations and linguistic commonalities to determine that the oldest tale of all was “The Smith and the Devil”. A story ‘as old as time’ has of course mutated and diverged through innumerable retellings, and been adapted to fit varied cultural values. The basic story is that of a blacksmith who outwits the devil, causing him to be fixed to a spot and only given leave when he had shared the dark magical arts of smelting and metalworking with the smith.

The association between iron and magic is widespread, and stems from long before the Iron Age. One of the oldest iron artefacts is a dagger found in the tomb of Tutankhamun, having been made circa 3,200 BCE, which is about 2,000 years before the Iron Age. How can this be?

The metal in Tutankhamun’s dagger was worked from iron that had been ‘a gift from the gods’, ‘the solidified tears of the sun’ that had fallen to earth in the form of what we now call meteorites. Traditionally, for one to mimic the work of God, or the gods, marks the individual as dabbling in the domain of the devil. There are many tales of smiths dealing with devils to secure the secrets of iron-smithing. In some stories the smith outwits the devil, in others he fails to do so, with tragic results.

The ancient tale was later Christianised in the West as the story of “Saint Dunstan and the Devil”, in which the devil takes the form of a comely maiden to tempt a hardworking and honest blacksmith away from his work. The blacksmith sees through the disguise when he notices that the temptress has cloven hooves and, using his tongs to grasp the devil’s snout, ejects him. The devil returns on another day as a wealthy merchant and offers the blacksmith riches in exchange for some sort of exclusive trade deal. The devil had, again, overlooked suitable footwear in his disguise and the cloven hooves give the game away once more! The smith uses his tongs again, but does not let go until the devil shares more secrets of furnace and forge, also promising never to bother any family who hangs one of the smith’s horse-shoes above the door of their abode. In France, variations of this tale are told of Saint Eligius.

Features of this folktale forge links in a chain that connects Wales via The Mabinogion and Huw Llwyd, through the stories of Eastern Europe, all the way to Kenya and Nigeria – though probably in the reverse direction, chronologically and linguistically speaking. OK? Bear with me.

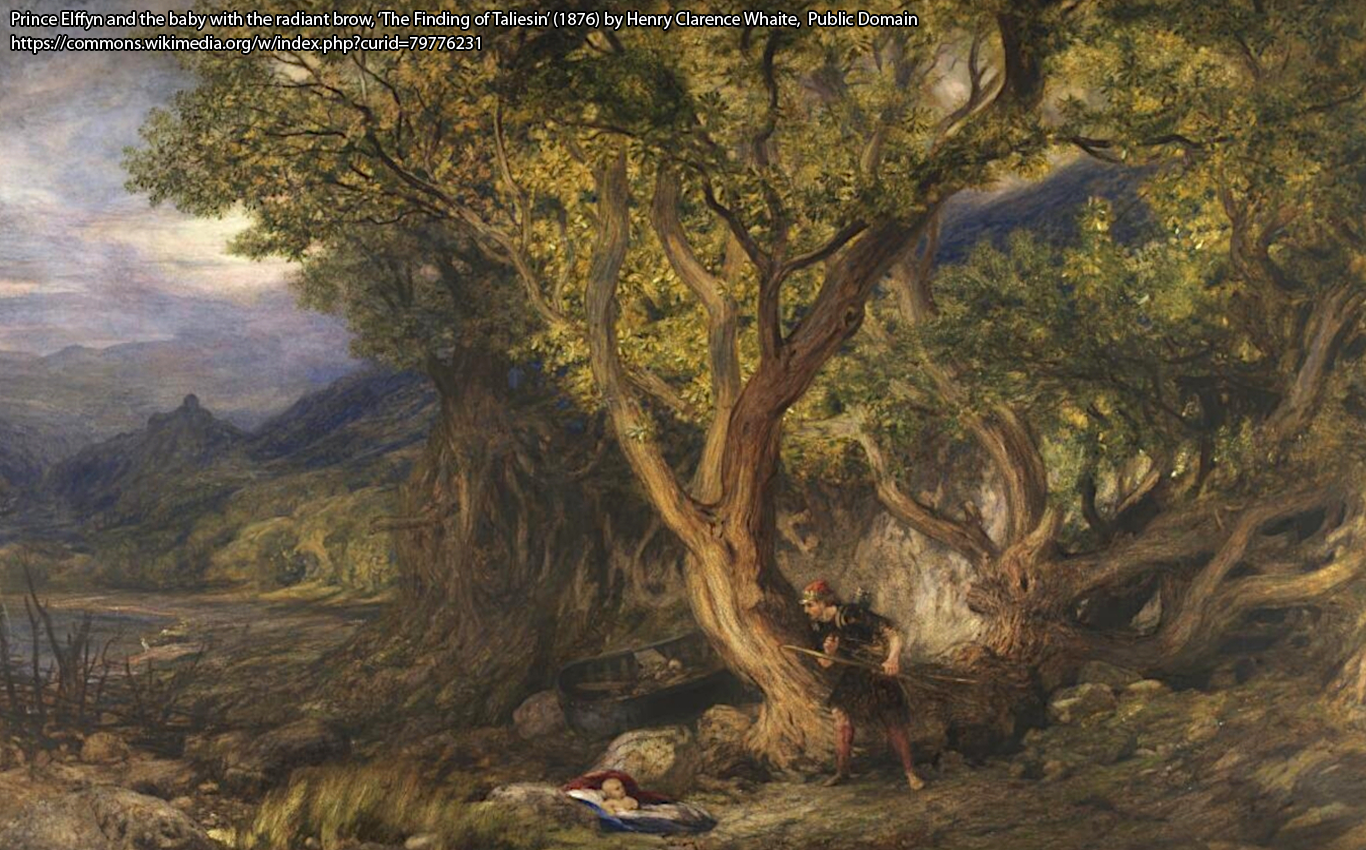

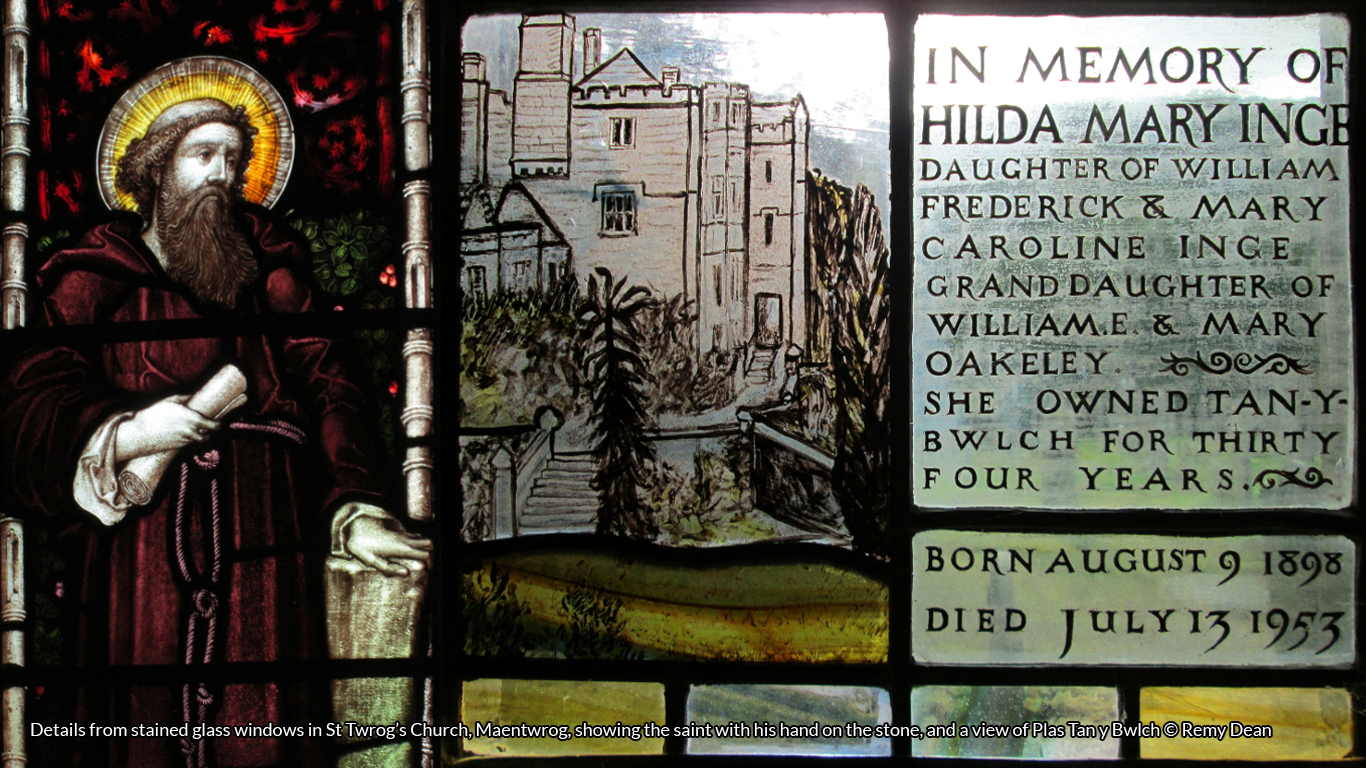

If you have read my previous articles here on #FolkloreThursday, you may know that I have been researching the Maentwrog area and had been fascinated by the stories surrounding Huw Llwyd, the real ‘Welsh Wizard’ also known as Huw Cynfal, due to his association with Cwm Cynfal, an area of land to which he attributed deep and ancient magical powers. It was unavoidable that I would also become embroiled in the rich and complex Mabinogion, a collection of interwoven Welsh folk-tales of gods and goddesses, kings and bards, a good many of which centre on the mountains and valleys surrounding Maentwrog. This research was being undertaken as part of my residency at Plas Tan y Bwlch, where artefacts from local archaeological excavations are on display. So, the story behind the excavation of nearby Bryn y Castell, above Cwm Cynfal, really grabbed my attention…

Historians had looked to the Mabinogion for clues to the locations of ancient sites and historic battles that may have taken place during the Dark Ages, or earlier. The Vale of Ffestiniog, the Moelwyn mountains, and the estuary at Maentwrog feature as important locations in the Mabinogion – King Pryderi dies in battle at Maentwrog and so the Hall of King Math fab Mathonwy, known as the ‘llys on the mountain’, should be nearby. If these stories are anything more than ‘fairytales’, then evidence of this llys or ‘grand hall’, should lie somewhere in the hills overlooking the territory.

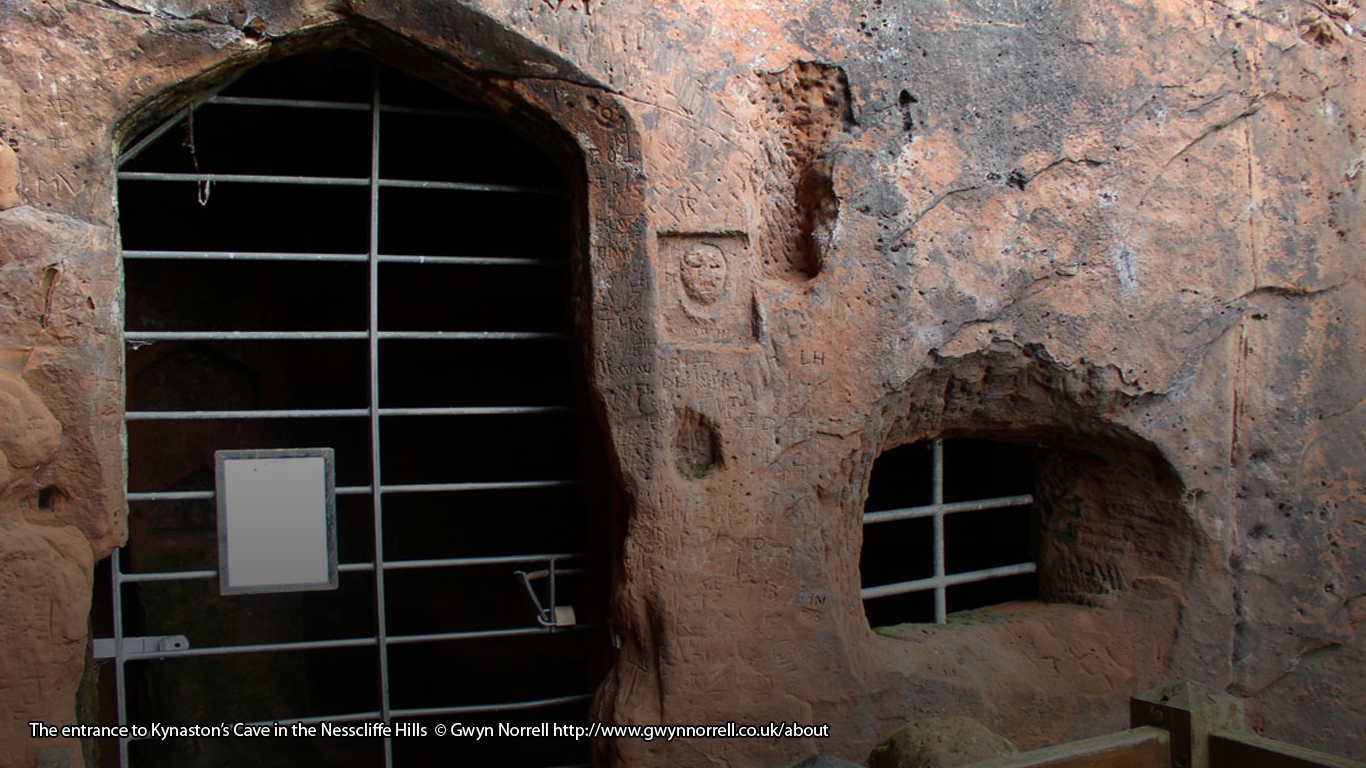

If you stand at the ancient crossing point marked by Twrog’s Stone, and scan the skyline, several potential locations present themselves. One of these is a small outcrop, traditionally known as ‘Bryn y Castell’ – ‘the hill of the castle’. Once dismissed as being named simply because of its passing resemblance to a castle, archaeologists decided to excavate there…and found a settlement scattered around a hill-fort!

At first considered to be a site built in the Dark Ages, further excavations, carried out from 1979 to 1985, uncovered structures dating back before 300 BCE. During the extensive excavations and partial reconstruction, an Iron Age forge and foundry were discovered. The amount of slag and other debris at the Bryn y Castell site was the largest quantity found at any British prehistoric site, indicating that this was once a hugely important social and economic hub and was central to the international trade in iron and metal goods – the first inklings of our modern industrial society. It seems that a major output of the fort forge were currency bars or trade-iron, which are also thought, by some, to have had ritual significance and may have been buried as protective boundary markers.

Archaeologist Peter Crew built replicas of the Bryn y Castell furnace and, through continuing experimentation, his team managed to extract iron from the pan-iron ore found in the nearby bogs using prehistoric materials and techniques. Items such as axe heads, blades and weights were then struck from the iron by blacksmiths. To make iron of this quality proved to be a long and arduous process, and would have required a plentiful supply of heavy bog-iron to be brought up to the fort, and then broken down to manageable sizes. Large amounts of wood and charcoal would have to be replenished continuously, and carefully, to avoid temperature fluctuations. Bellows would need to be worked at a constant rhythm for much longer that one man could endure. How did they manage to maintain the constant, high temperatures for long enough to produce iron that was, for the time, so pure? Peter Crew looked for clues in comparative cultures and found furnaces of a similar design still in use in regions of Africa, indicating a possible link between the prehistoric cultures.

In Kenya, even today, tribal smiths are looked upon in much the same way as ‘witch-doctors’; both feared and revered for their magical powers. They are believed to command the mystical life force, and are often ostracised from the tribe and expected to live apart from them.

Attitudes in Nigeria are a little different to Kenya. Here, it is more usual for the tribal smiths to be respected as ‘priests’, healers, or spiritual guides, and to preside at funerals as well as bringing the community together around them in iron-working rituals. Traditional dances incorporate replenishing the charcoal and working the bellows. Those few working more closely with the smith-priest – usually his sons – are effectively apprenticed, and learn some of the ‘tricks of the trade’ for future generations. In order to reach and maintain the exact temperatures necessary for smelting quality iron, the rituals can last many hours, possibly days. The finale is the beating out of a sheet of magical iron which is laid over a pit in the ground to somehow, symbolically control the numbers of locusts to protect the next season’s crops.

Here we can still see folklore very much in action, and there is a resonance between the tribal smith-priests of Africa and the saint-smiths of our European stories. This gives many clues about how those prehistoric iron-age workers at Bryn y Castell would have, almost certainly, incorporated magic and ritual into the smelting and forging of their metal… and how our oldest tales contain clues to ancient technologies and links between far-flung cultures.

Thanks again to Twm Elias, Andrew Oughton and all at Plas Tan y Bwlch, the Snowdonia National Park Environmental Studies Centre.

Recommended books from #FolkloreThursday

References & Further Reading

Merfyn Williams and Twm Elias, 2015, Plas Tan y Bwlch, Snowdonia National Park Centre, ISBN 978-1-84524-237-4

Peter Crew, 2009, Ironworking in Merioneth from prehistory to the 18th century, Darlith Goffa Merfyn Williams Memorial Lectures, Plas Tan y Bwlch, Snowdonia National Park Centre

Peter Crew Research Papers, On-line Academia Catalogue, http://independent.academia.edu/PeterCrew

Gwynedd Archaeological Trust, http://www.heneb.co.uk/

Sara Graça da Silva and Jamshid J Tehrani, 2016, Comparative phylogenetic analyses uncover the ancient roots of Indo-European folktales, The Royal Society Open Science Journal, http://rsos.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/3/1/150645

Natalie Zutter, 2016, Is This One of Mankind’s Oldest Fairy Tales? http://www.tor.com/2016/02/22/fairy-tales-older-linguistic-analysis/

Emma George Ross, 2002, The Age of Iron in West Africa, Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York Metropolitan Museum of Art, http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/iron/hd_iron.htm

W. E. A van Beek, 2011, The Forge and the Funeral: The Smith in Kapsiki/Higi Culture, Project MUSE Michigan State University Press ISBN: 978-1611861662

Julian Henderson, 2013, The Science and Archaeology of Materials: An Investigation of Inorganic Materials, Routledge, ISBN: 978-0415199346

George Monbiot, 1994, The Smith and the Devil, http://www.monbiot.com/1994/01/01/smith-and-the-devil/

Peter A. Rogers, 1996, Review of Iron, Gender and Power: Rituals of Transformation in African Societies by Eugenia W Herbert, H-Net Reviews, http://www.h-net.org/reviews/showrev.php?id=469