This article is about clowns. If you have clourophobia you might want to look away now. Not many forms of entertainment have their own phobia, yet there seems to be something about clowns that gets deep into our psyche.

Whether it’s the mocking face of Pennywise, or the seemingly mundane black and white photo of John Wayne Gacy whose menace comes from knowing the facts surrounding Pogo the Clown’s crimes, pale leering faces continue to terrify vast swathes of the population.

Commentators have pinpointed the first event in the most recent clown panic to Greenville, South Carolina. On the 19th August 2016 a small boy tells his mother, Donna Arnold, about an encounter with two clowns in the woods who try to lure him into an abandoned house. whispering to the child as they encouraged him to go with him. One wears a red wig, while the other has a black star painted on their face. Presumably the child had enough sense not to follow them, enabling him to report back to his mother.

The first few sightings were low level, and conformed to other episodic clown scare events. In Paul Sieveking’s article for Fortean Times he chronicles the events up to October 2016, first in the United States. Sightings took many different forms such as the clown in Lucedale, Mississippi, who approached a woman in a parked car, knocked on the window, then escaped into the woods, or the group of children in Northampton County, Pennsylvania, who told police they were chased by three clowns who then got into a white vehicle. The sightings reached an epidemic velocity, spreading globally including to the United Kingdom. For example on the 6th October a school in Clacton, Essex, is locked down after two clowns in a van invite some girls to a party, while on the same day five clowns were spotted in Sudbury, Suffolk.

2016 was not the first time a clown panic has occurred. Loren Coleman invented the phrase phantom clown theory on the back of a similar set of sightings in 1981, starting in Boston and spreading to several cities across the United States. Most of these encounters had a similar manifestation, with the untraceable clowns trying to lure small children into vans. The starting point seems to be in Brookline, Massachusetts, where Lawrence Elementary pupils reported two clowns trying to talk them into a black van.

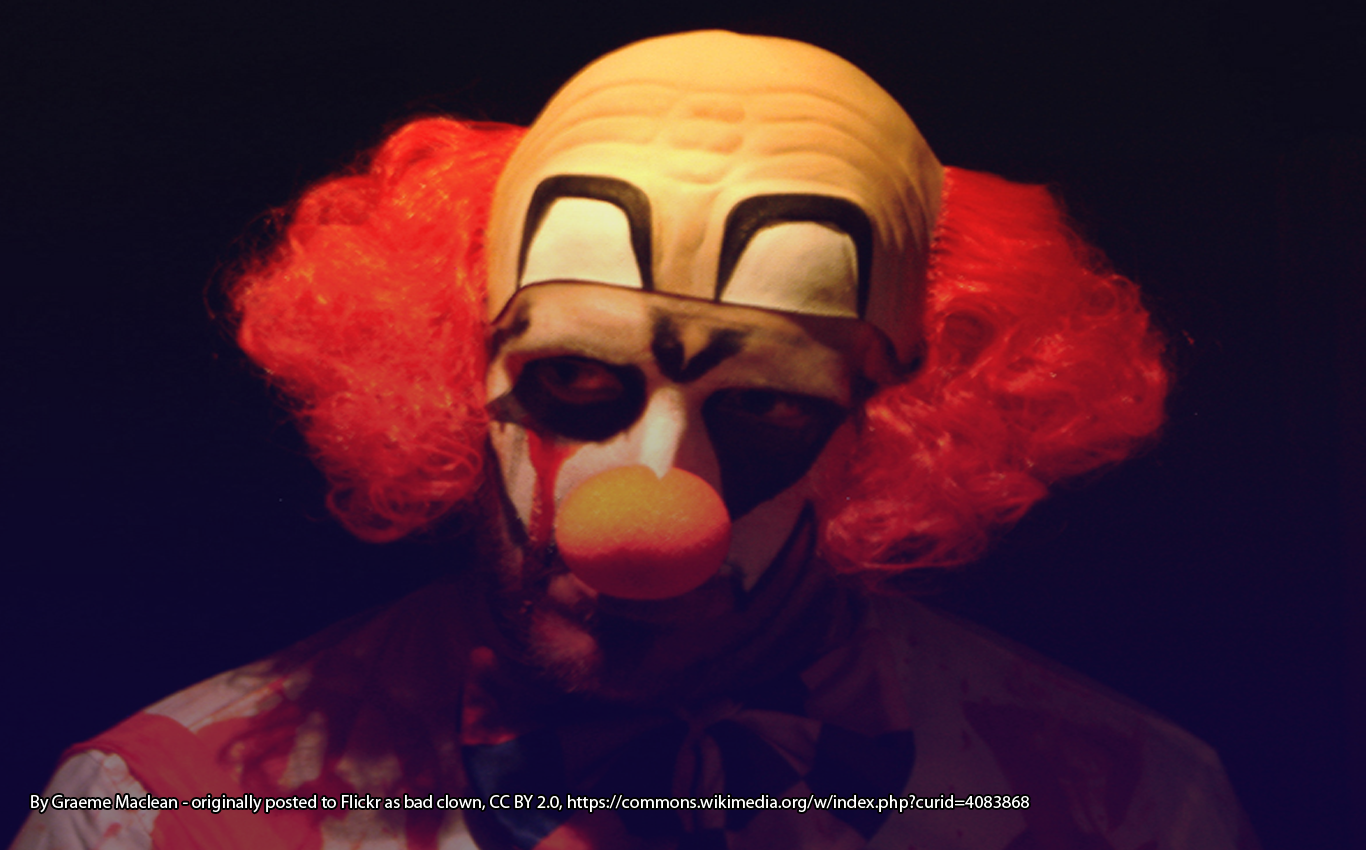

Robert Bartholomew of New Zealand’s Botany College is a long term researcher of mass hysteria, and is quoted in Fortean Times as crediting the acceleration of the 2016 sightings down to two main factors. The first is the speed information can be transmitted via the internet, particularly visual media that seems to confirm the foundations of the panic. The second factor is the fear of otherness. The blankness and unknowability of the clown persona allows these fears to be projected onto the phantom, in the same way the fear of the malevolent stranger was projected through the earlier phantom clown panic of the 1980s.

In his book Bad Clowns, author Ben Radford has studied the long and complex history of clowns from ancient Greece through the various theatrical forms right up to the present day, a history very ingrained in our societies.

From Momus, Greek God of Ridicule, through stories like ‘Hop-Frog’ by Edgar Allan Poe, to songs such as Danny Schmidt’s ‘A Circus of Clowns’, the mocking, destructive, and dangerous clown is a constant presence within society.

One of the major changes between the earlier phantom clown phenomenon and the later 2016 appearances is the concreteness of the clown manifestations. In 1982 the clowns seem to lurk around the edges of children’s imaginations. In 2016 they exist in a very real sense, captured on photo and mobile phone footage with some of the clowns finding themselves in handcuffs and on their way to the police station (for example Johnathon Martin taken into custody by police in Kentucky).

In some cases, the clown costume fulfils its role of masking darker impulses, allowing people to manifest criminal behaviour behind the identity of this ancient symbol. People are attacked by weapon wielding clowns, such as Simon Chinnery of Blackburn who received injuries to his hands from a clown who attacked him with a knife.

Sieveking records over fifty incidents during the core period of sightings, and it seems to have died down by the end of October 2016. It’s clear the role that the internet has played in the spread of the phenomena. Urban legends are now told by the light of monitors rather than via the more traditional forms of transmission such as local papers and campfire tales. This has vastly accelerated the speed the phenomena spreads around the world. Also the improvement in technology has probably contributed to the volume of sightings. We live in a time of easy access when the prank has gained a new momentum with the ease that they can traverse the globe. Although the clown flap of 2016 was drawing on older clowning imagery as a way of inducing fear, it was a very modern manifestation of the darker side of clowning in its own right. Those individuals who donned scare wigs and facepaint or masks to go out and scare populations are part of that long tradition of the clown as the unpredictable fear lying at the heart of a lot of the prank trends in the age of the internet. Not only did the people who dressed as clowns and take to the street wear the trappings of the trickster, they also drew on the power of the trickster tradition in a very 21st century context.

We shouldn’t diminish the fear of encountering a masked person standing on a bridge with a rifle, or waving around a knife on a dark street. However, we need to understand that these pranks and criminal acts are themselves as much a manifestation of the chaotic energy of Momus as performers tumbling out of a shattered multicoloured car onto circus ring sawdust to the nervous applause of children.

References & Further Reading

Paul Sieveking, ‘Attack of the Killer Clowns’, Fortean Times FT347

Loren Coleman, 1983, Mysterious America, Paraview Press

Benjamin Radford, 2016, Bad Clowns, University of New Mexico Press

Marion Rankine, 2016, ‘Clowns’, TLS https://www.the-tls.co.uk/articles/clowns/

Edgar Allan Poe, 1849, ‘Hop Frog’

Matthew Dessm, 2016, ‘The Wave of Clown Sightings Is Nothing To Worry About. It Happens Every Few Years!‘ Slate.com