In North America, legends of haunted places often claim they have been built on an “Indian burial ground.” Indigenous burial ground urban legends are so widely shared they’ve become a part of popular culture. Writers used them repeatedly as a literary device in horror until they became a comedic cliché and eventually a meme.

Amityville Horror: A True Story by Jay Anson is often erroneously said to be where the trope originated from. Anson claimed the Amityville house was built on an old Shinnecocks “enclosure for the sick, mad, and dying.” People were “penned up” on the location until they died of exposure. They were not buried there, he said, because the Shinnecocks believed the land was infested with demons.

Anson’s 1977 book became a runaway bestseller. Later that year, celebrity TV ghost hunter Hans Holzer investigated the Amityville house with medium Ethan Johnson Meyers and three others. According to Holzer, the ghost of an Indigenous chief contacted medium Meyers and said he murdered Ronald Defeo Jr.’s family—including four younger siblings—by possessing him. Until then, the victims had been blamed for the haunting, but now an Indigenous ghost was the real culprit. The 1979 Amityville Horror movie adapted Holzer’s unfounded claims into the script.

According to numerous statements, the Shinnecocks never lived in the area—it wasn’t even part of their traditional territory—and there was never a burial ground at the site. No archeological evidence or oral history has ever supported this claim. Holzer and Meyers had successfully used the lesser-known—but common—Indigenous burial ground story to legitimize their own positions as experts by adding to Anson’s original tainted Indigenous land story.

Around the same time, Disney theme parks launched their Big Thunder Mountain Railroad rides in California in 1979 and in Florida in 1980. Details on how the story has evolved over the years are hard to find—but the ride is said to be a runaway train travelling through a haunted mine and ghost town built on Indigenous burial grounds. A Disney blogger in 2020 said an employee told her Indigenous spirits can be heard chanting in the ride, but she could only hear drums. Hundreds of thousands of people were exposed to the Indigenous burial ground trope thanks to Disney.

In 1983, Stephen King used an Indigenous burial ground as a literary device in Pet Cemetery. He also appropriated a version of the Algonquian’s wendigo story. The book became a movie shortly thereafter. Renee L. Berland in The National Uncanny: Indian Ghosts and American Subjects said many early American writers were obsessed with Indigenous ghosts before Pet Cemetery was written, but King’s book became “one of the most popular novels that has ever been published.”

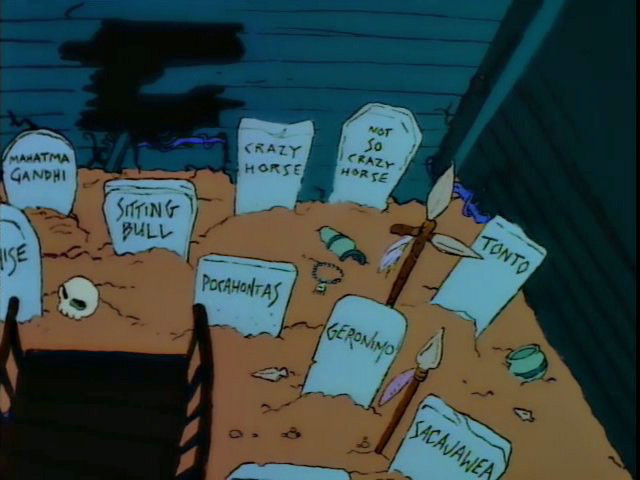

The burial ground trope had appeared earlier in Kubrick’s 1980 adaption of The Shining—also by King—and was mentioned as not being the cause of the haunting in the 1982 Poltergeist movie. It’s since been used in Buffy the Vampire Slayer, The Real Ghost Busters cartoon, and in several other TV shows, books, and games. Popular comedy series have poked fun at it over the years, including The Simpsons, Friends, South Park, Family Guy, Parks and Recreation, and others. How to Survive a Horror Movie by Seth Grahame-Smith says one way to confirm a house is haunted is by answering the question: “Are Native Americans constantly showing up to ask, ‘What happened to our cemetery?’”

North American ghost hunting TV shows often use Indigenous burial grounds as an explanation whenever “demonic” entities are said to be present. Ghost Adventures, in particular, seems to have a formula that leads them to conclude Indigenous ghosts are to blame. These shows are not meant to be comedic. Holzer’s shift-the-blame-to-nonwhite-ghosts strategy has become more mainstream than ever.

Perhaps it was inevitable. In 2011, satire news source The Onion released a video called “Report: Economy Failing Because U.S. Built on Ancient Indian Burial Grounds.” It’s still available on YouTube. It’s a brilliant piece of comedy. Panelists discuss a congressional report claiming most problems in the United States are caused by the nation having been built on ancient burial grounds. One of them believes Republicans are trying to paint Obama as soft on poltergeists—as they are demanding a blood offering! There’s even a voice-of-reason panelist who claims it’s just the settling of America’s foundations. Every hardship is caused by “Indian ghosts,” most panelists agree, including the existence of poor people.

Since then, there have been thousands of posts on Twitter and threads on Reddit essentially saying the same thing. There are photo memes (image macros) and videos, as well. In recent months, awareness of the trope has grown thanks to several articles—though Atlas Obscura may have been the first nonacademic source to do so in 2008. The memes and original stories that started the movement have never been given the same critical attention as the trope has.

A person cannot look at Indigenous burial ground tropes or memes without examining their folkloric origins. This is where things get complicated. We can reasonably assume there are real burial grounds and rumoured—but not true—burial grounds. Some of the former are believed to be actual haunted locations by Indigenous people. But most settler stories are not true. They instead project traditional Christian fears of “uncivilized” people. Settler ideas about consecrated ground, the name of Christ as a solution for paranormal activity, and Heaven as a place only open to denominational believers are somewhat to blame.

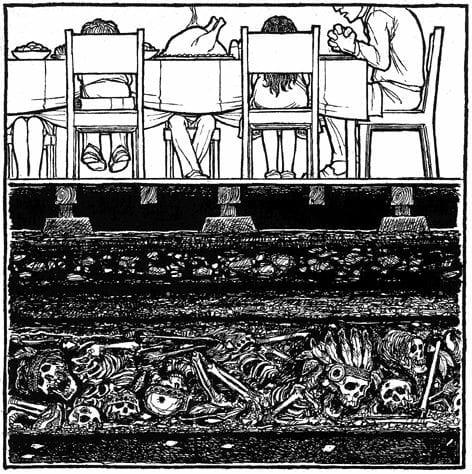

The best counterargument to this inferior-earthbound ghosts perspective is a concept called “Settler Guilt.” A popular theory about ghosts—of course—is that they are spirits of people who were wronged in life—sometimes even murdered. If our ancestors committed horrible acts against the first people, then maybe we are being haunted on some level as we reap the benefits in resources, food, and trade in ways that continue to this day (every person who lives in a once-colonial country has). The above illustration by Ron Cobb appeared in Los Angeles Free Press in 1966 captures this sentiment in conjunction with Thanksgiving. Some might believe we are haunted because of the sins of our forefathers and foremothers.

Settler Guilt might be why those sympathetic to Indigenous lives still spread the memes and stories. But claiming all places are Indigenous burial grounds delegitimizes actual burial sites and minimizes real crimes and injustices—from criminals like Defeo to sites of genocide such as the residential school graveyards.

Fear of Indigenous ghosts predates the haunted burial ground legends. Newspapers in 1890, for example, reflected colonist dread as the Ghost Dance movement gained momentum across North America. The ceremonial dance was meant to raise the spirits of recently deceased tribe members for protection against settler injustices. Public fear led to the massacre at Wounded Knee, where the US Army killed 150-300 Lakota people, said to be mostly women, children, and Elders. They feared resurrected ghosts, but were not afraid of making new ones.

The oldest report of an Indigenous grave causing a haunting in British Columbia—where I live in Canada—I’ve come across is from 1924. Victoria Daily Times reported that seven road builders were haunted for four nights where they had built their camp. A “whishing” sound and rapping noises were heard between 8 PM to 2 AM every night. The men searched the dark with lanterns and looked for animal prints during the day, but could find nothing. They moved their camp after concluding it was built on the grave of a “Red Indian.”

City Archivist Major Mathews told a Province reporter in 1940 that Vancouver had “Indian ghosts,” but he did not elaborate. It was one sentence in a section dedicated to youth about Halloween parties and witches. It was the only haunting mentioned.

An interesting Ontario story appeared in the Vancouver Sun in 1946, about a headless woman’s ghost wearing a skirt. The four-paragraph article said she had been seen near the secret site of Tecumseh’s grave. This is fascinating, as Tecumseh was a famous chief who tried to unite Indigenous groups against American expansion. He allied with the British during the War of 1812 and was killed in 1813. His confederacy then collapsed and he became a romanticized folk hero. The woman’s ghost had only been seen in an area rumoured to be his burial site, but it was deemed important enough to be included as part of the report.

“The Ghost of Graveyard Flats” by Bjarne Kirchhoff appeared in the Vancouver Sun in 1950. Kirchhoff was a pulp writer whose credits include an online-available science fiction story and a handful of publications in the Sun. It’s difficult to know where else he was published, but it’s notable his Indigenous burial ground was thought to be haunted by a wendigo 33 years before Stephen King’s was.

The Times Colonist reported a Comox haunting in 1966 that eventually made its way into several books. Earlier 1940’s versions were of a mist-like apparition one witness claimed became a woman who danced a couple of steps. By the 1960s, “Bloody Mary” had transformed into an Indigenous woman another witness said was “young and well-stacked.” Later books called her Dancing Mary. The story evolved to include either her grave or a massacre site. It’s a confusing story, as there are paranormal reports possibly unrelated to her and a settler cemetery involved.

In 1958, Colonist reporter Bert Benny said he was disappointed with how few hauntings there were to write about in our province’s capital of Victoria. By the 1980s, there were many more thanks to local ghost hunters Robin Skelton and Jean Kozacari—both who claimed to have psychic abilities. Ghost tourism arrived soon thereafter and Victoria became first “very haunted,” then one of the most haunted cities in Canada. The two most common reasons given are the city’s proximity to water and it being built on an Indigenous burial ground. To someone who has lived in the Southwestern United States and Afghanistan, as well as travelled in India, the water theory sounds childlike, but it’s the burial ground stories that are shameful.

One news article—quoting a historian— recently made this claim. They mentioned well-known burial mounds in Beacon Hill Park, around Cadboro Bay, and on Saltspring Island. Before Victoria’s tourism scene became popular, the park claimed to have 23 mounds—none that were ever built upon to my knowledge. Cadboro Bay area was said to have around a hundred, but that is in a neighbouring city not even a part of Victoria. Saltspring Island, of course, isn’t relevant. Compared to the tens of thousands of nonIndigenous bodies in cemeteries, it makes one contemplate the power of one Indigenous grave. The Indigenous burial ground stories don’t make sense, either. These burial mounds have always been interesting to researchers, because local First Nations only used cairns in ancient times. Bodies have been put in trees, on raised platforms, or inside of caves near the shoreline for 1500 years. Early settlers collected every bone they could find as souvenirs. It’s not to say Indigenous remains are never found, because they are—but the city wasn’t built on a mega burial ground as many claim it was.

Another example is found in a Gathering of Ghosts by Robin Skelton and Jean Kozacari. Published in 1989, “The Indian Inheritance” chapter claims tainted land is to blame for a cult’s actions near Nanaimo. After incorrectly saying it was Kwakiutl [sic] territory and a slave-body dump site, the authors state: “It seems not unlikely that the long history of Indian raids, feasts, and ritual killings accounted in part for the way in which Brother Twelve’s initially peaceful and gentle community became disturbed… The problem was the land and its history. It was crying out for blood. The evil was in the earth itself.” Like Amityville, these facts were not true. But Indigenous ghosts were painted as the real culprits—or in this case, their evil soil made sentient. Body dumps? Ritual killings? Evil feasts? What makes this story particularly brutal isn’t the hateful depiction of the local Indigenous people, it’s that Skelton was a respected university professor and admired public figure.

Indigenous burial ground stories qualifying as urban legends are less documented. I first heard one in the 1980s about my home neighbourhood of MacArthur Drive in Prince Albert, Saskatchewan—said to be built on an Indigenous burial ground. Every time I heard it, a different adult was said to be the source. The ghost of a chief wearing a headdress appeared to one resident—or so I heard. It’s fascinating how often Indigenous royalty will appear to the common folk.

Besides Victoria, I’ve heard Indigenous burial ground claims about the South Crescent Neighbourhood in Port Alberni, a road in Courteney, the old Forbidden Plateau ski resort, and several others I suspect have no basis in fact. What makes the claims urban legends, besides the friend-of-a-friend as the source aspect, is that they are people of European background who are sharing the tales of Indigenous ghosts.

There have been actual stories of spirits associated with ancestral remains in museums and at archeological digs, but the accounts are not ideal for consumerism. Phantom Past, Indigenous Presence: Native Ghosts in North American History and Culture, has a few. Indigenous communities usually have designated storytellers and knowledge keepers who are allowed to share with outsiders, as many stories are intentionally private. Beyond settler ghost clichés of ancient people dancing around in regalia (vs. blue jeans), a widespread traditional belief is that even talking about a deceased person can cause a haunting. Also relevant is the abusive residential schools’ beliefs taught to children—such as Jesus being the only cure for evil.

“Traditional belief” is not viewed as myth or legend and even the term “lore” can be tricky. Entire cultures were erased. Many languages and stories were lost forever. Courts ruled that even petroglyphs are copyright protected now. Terms like “Indigenous” are preferred over others, but this changes often and is different between countries—even the U.S. and Canada—and older generations sometimes identify with labels considered offensive amongst younger community members. Besides the disrespectful burial ground terminology, appropriation is often a factor.

When I was at field school at the University of Fairbanks in Alaska, learning protocol for recording Indigenous oral stories, I saw the Alutiiq Museum chart they were using for reference. If the experts and Elders refer to this, I thought, then I should too. It’s a learning process, but being as respectful as possible is the only way forward.

Why are the Indigenous burial ground stories so popular? And what does it say about us that our mainstream explanation for evil hauntings in North America is the ghosts of the people our ancestors actually wronged? Settler Guilt isn’t good enough. Indigenous people are not evil or demonic. Their traditional versions of heaven are often more beautiful and less judgmental than many settler beliefs ever were.

*Images, except where stated, have been reproduced under the UK terms of fair dealing for criticism, review and reporting current events (section 30 CDPA, Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.)