Odin, the one-eyed god, sits upon his throne in Valhalla, feeding his wolves Geri and Freki by hand. Shields and mail coats fill the warrior-haunted room. Other wolves roam the hall, as well. Only the most valorous warriors have been invited to the feast. Odin welcomes them all. For this is how he will build his great army for Ragnorok – the end of days.

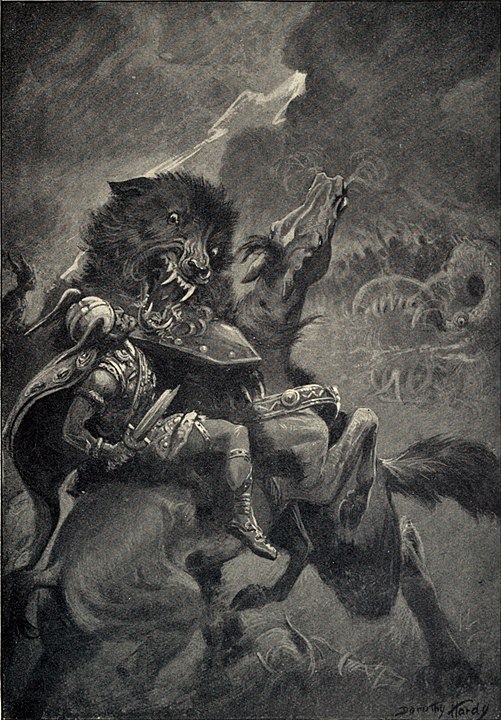

Loki’s son Fenrir, the great wolf, is bound to the World Tree Yggdrasil. To stop him from consuming the world and the heavens, the Aesir tricked the wolf into being chained to the tree. Fenrir was cunning, though, and he suspected trickery. So the god Tyr placed his sword hand inside of the wolf’s mouth as a gesture of good will. It is said the gods laughed when the wolf was bound – all except Tyr: he lost his hand. This is why your wrist is called the “wolf’s joint.”

Two more wolves race across the sky, pursuing the chariots of the Sun and the Moon. Their names are Skoll and Hati Hróðvitnisson. One day, the Sun will be captured and will be swallowed whole. The Moon will be consumed as well. The world will be thrust into darkness and ice will cover everything. Fenrir will break free from his bindings, the World Serpent will rise from the depths of the sea, and the Aesir and humans will be destroyed… all but a very few. This is Ragnorok. Wolves will cause the destruction of all there is.

Inuit say the very first man married a she-wolf. Their children were born in pairs – one female and one male – each speaking a different language. The children left the den and wandered far and wide, eventually populating the lengths of the earth. The Mongols have a similar story. Their ancestors were a blue-gray wolf and a fallow doe. Genghis Khan was their direct descendent.

Nomadic Turks spoke of their forefather, as well. He had also married a she-wolf. He was the only survivor when raiders massacred his tribe. The enemy’s chief cut off his feet and threw him into a pond. A lone wolf pulled him out and fed him, restoring him to health and eventually becoming his wife. They had ten sons and each of them took foreign women as brides. These were the very first Turks. Their offspring for generations would howl before going into battle, calling upon their wolf ancestor to help them obtain victory.

Stories of wolf marriages also occur in First Nations and Native American lore. The stories are often similar to one another. A relative or fellow villager will betray the man or woman, before leaving them for dead. Wolves will then save the outcast and one of them will marry him or her. Eventually, the human will return to their village or tribe. They almost always have powers gifted to them by the wolves – which will help them reclaim their lost place and exact revenge if needed.

Children raised by wolves is a popular global motif. Not just in Indigenous cultures, either. The most famous being the one of Romulus and Remus, the founders of Rome. The story has evolved through the ages, but the best-known version claims their mother was a virgin and that their father was the war god Mars. In typical Greek-Roman fashion, their great uncle – the king – abandoned them on the River Tiber in an attempt to avoid a prophecy of his death. Tiberinus, the god of the river, spared the twins. A wolf suckled the boys until a shepherd adopted them. Eventually, Romulus and Remus helped their grandfather retake his thrown and kill their great uncle.

From antiquity to relatively modern times, there are stories of children who have been raised by wolves. The Wolf Girl of Devil’s River in Texas is a more modern example. She is said to have lived sometime around 1835. The frontier orphan was originally thought to have died, but had actually been raised by wolves. She would run alongside her pack and attack livestock with them. Once, she was even rescued by the wolves after some herdsmen had captured her. The last time she was seen – in all of her wildness – two young wolf pups were trailing close behind her.

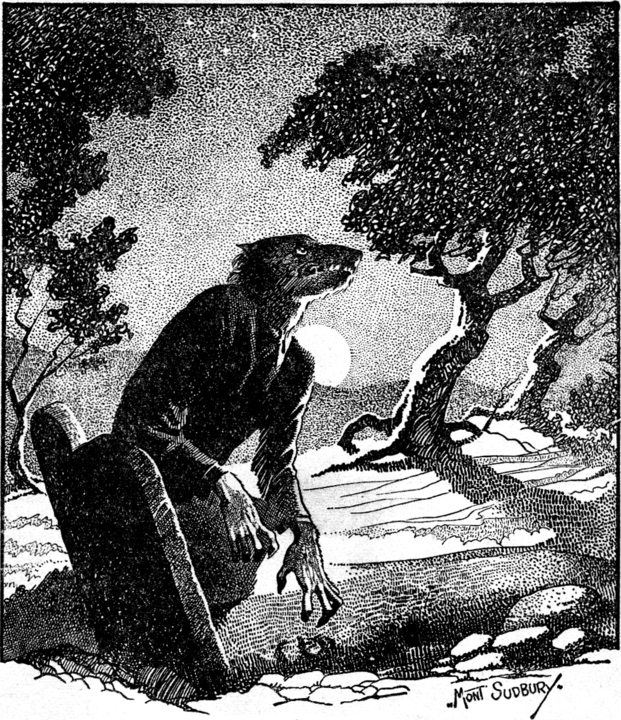

Interbreeding between humans and wolves might explain why the wolf’s eyes are human-like. The Bella Coola in the Pacific Northwest say that someone once tried to turn all of the animals into humans, but only succeeded in changing the eyes of the wolf. Montague Summers in The Werewolf in Lore and Legend said that in Northern Europe a good way to spot a werewolf was through its human eyes, as our eyes are said to be the mirrors of our soul, so remain unchanged. Yellow eyes, in particular, can be an indication of additional supernatural powers.

In North America, Indigenous people almost always consider wolves to be their relatives. Nations who once relied on hunting more than agriculture admire the wolf the most, but so do warrior societies. In Wolves and Men, Barry Lopez said this is because the wolf is seen as strong individually, but that it can also submerge itself into the needs of the collective pack – or tribe – at the same time.

The Skidi Pawnee once called Sirius the wolf star, which coincides with the Chinese astrological name of The Celestial Wolf. Pawnee teachings say that the wolf was the first animal to be killed, which in turn brought death to the rest of the world. This might be why howling is often considered a message from the spirit world in Indigenous belief. One Nuu-chah-nulth story from Vancouver Island claims that wolves are the returned spirits of the dead in their new physical form. Less directly, a sharp wolf bone was used to prick a person’s chest during the Aztec ritual of last rites.

Pacific Northwest Native Americans and First Nations traditionally believe that the orca – or killer whale – and the wolf are actually the same creature. The wolf pack dives into the waves and becomes a pack in the sea, using the same hunting strategies beneath the surface of the water. They will then leap ashore and become wolves once more, hunting along the beaches and through the rainforests.

It is possible that the wolf was never considered a food animal in North America. The pelt and other medicine parts were usually all that was taken after a kill. Before a traditional wolf hunt, the Cheyenne – and others nations – would first conduct a ceremony of purification. The Cherokee also believe reverence should be given, because a wolf hunt invites retribution from other wolves and can cause game to disappear. A weapon that kills a wolf will never work again. This level of respect might have benefited the wolf elsewhere, if only it had spread across the world.

The Japanese wolf has been extinct for over a hundred years, but sightings of it are sometimes still reported. These are hard to verify, as the wolf can hide behind a single reed of grass, take the form of a sparrow, or become completely invisible.

As a guardian of the mountains, the Japanese wolf is the personification of the wilderness and a means to communicate with it. In the Yamanshi Prefecture, food was once left out as offerings to wolves whenever they had new pups. A Wakayama Prefecture story tells of a village that once saved a wolf’s life. The wolf later visited them, leaving a deer outside of their village as a token of gratitude.

Japan’s wolf is small compared to other wolves, but it is fearless, especially at night. A lone wolf will follow a traveller through the woods back to their home, protecting them if they are a honourable person, but eating them if they are not.

The hair of a Japanese wolf’s eyebrow is believed to have magical properties. It is always freely given by the wolf and has never been taken by force. In some stories, the hair gives its owner the ability to see people’s true forms when held above the observer’s eye. People without honour might be animals in disguise. In some versions, simply possessing the hair might give its owner good fortune. Wolf hair is also said to be magical in a thirteenth-century French bestiary, where it’s stated that a tuft of hair from a wolf’s tail is a powerful aphrodisiac.

When he was young, the god Krishna turned many of his hairs into hundreds of wolves. He needed to convince his fellow forest herders it was time to move to a different forest. The wolves ate calves, abducted children, and attacked people at random, forcing them to relocate to their new location.

Wolf omens were something to take seriously in India, especially by the Thugee worshipers of Kali. Thugs practiced a bloodless type of assassination using strangulation. Every person they killed and robbed was actually a sacrifice to the goddess. While carrying out a mission, if a wolf crossed the road from the left it was seen as a sign to cancel the attack. If a wolf crossed the path from the right it meant the goddess wanted the killing to proceed. If a wolf howled during the day the thugs were to leave the area. Howls from midnight to dawn were also bad signs. An evening howl was indifferent. Omens were seen as direct orders from Kali, none of them as important as those from wolves.

The wolf is also connected to Rutu, the death spirit (or disease god) of the Sami. The missionary Randulf said the wolf was called Rutu’s Hound, while others called wolves “dogs of the death spirit.”

In Sweden, wolves serve the forest witches, the Vargamors. The animals are said to be under the witches’ protection and control. Some believe the women seduce men to feed to their wolves. Others claim the Vargamors are old women who transform their victims into wolves of servitude.

Zeus once turned the king of Acadia into a wolf, after being served human flesh at his table. Some say, the king was the first werewolf. In another Greek story, a pregnant Leto disguised herself as a wolf as she fled the rage of Hera, hidden amongst a pack of wolves. After she escaped she gave birth to Zeus’s son Apollo, who became associated with wolves as a result. Several of his temples viewed the wolf as sacred.

Stories of werewolves were common across Europe until relatively modern times. Herodotus wrote that the Neuriuns (present day Russia) turned into wolves a few days each year. And there is a Russian spell in Sabine Baring Gould’s 1865 Book of Were-Wolves describing how to become a wolf. In Bosnia, this could happen simply if a wolf licked your blood. Elsewhere, there was a belief that drinking water from a paw print could also turn you. In Poland, a strip of human skin placed across the threshold of a house hosting a wedding would change all who stepped over it into wolves.

All over Europe, wolves became associated with death and the spirit world. At eleven come the wolves, at twelve the tombs of the dead open, said one German folk rhyme. In Slavic lore, the wolf was the most frequent metamorphosis of the vampire. A traditional Serb belief said that vampires needed to transform into wolves. Another that a vampire could not harm a wolf, but that a wolf’s bite could destroy it. The Greek werewolf was believed destined to become a vampire. The living person’s soul would leave its body and enter a wolf it possessed. But after they died, they became undead. Another Slavic death belief said that a person born on the same day as a wolf would die when the animal did.

Eventually, the Church began to persecute werewolves and wolf fraternization. One woman in Switzerland was sentenced to death in 1423 for having consorted with wolves, including riding them across the night sky – in much the same way as the giantess Hyrrokin does in the Prose Edda.

In 1487, the Malleus Maleficarum (Hammer of Witches) claimed werewolves served the Devil, giving the rural stories legitimacy and the church an official enemy. It was generally believed witches could take the form of a wolf, until their animals were replaced by cats, hares, and dogs in areas the wolf had been eradicated. A sermon at Strasbourg in 1508 proposed there were seven reasons why wolves ate “men and children”. These were hunger, savageness, old age (humans were easier prey), experience (they had already tasted and liked humans), madness, the Devil, and God’s punishment.

It hadn’t always been this way. The History of Saint Edmund said that when invading Danes decapitated a 9th century English king, a lone wolf guarded his head for a year – until the king was properly buried. Celtic heroes like Taliesin and Gwydion had assumed the form of wolves, as well. In Scandinavia, North Germany, and the Netherlands, it was actually lucky to come across a wolf (or a bear) on your journey – but it was unlucky to see a hare. There were even stories of saints having wolves as disciples, being suckled by them, and of wolves giving sermons.

Be that as it may, wolves have always been the enemy of herdsmen, which is reflected in Aesop’s fables and in many children’s stories written since. According to Dante, wolves were seducers, hypocrites, magicians, thieves, and liars. Fables described wolves as veraciously hungry and unusually stupid. This stereotype migrated as far east as China.

The 13th century Welsh story of Gelert further illustrates how wolves were viewed in Christian communities. One day, Prince Llewelyn went out hunting, leaving his faithful hound Gelert behind to guard his baby. When he returned later that day, his son was missing and his hound had blood around his mouth. The prince killed his dog in a rage. Soon, however, Prince Llewelyn discovered his son alive beneath his overturned cradle. He also found the body of a slain wolf. For reasons unknown, no humans had been left to watch over or feed the baby. The wolf had decided to enter the keep in search of prey and was killed by the protective hound. Heartbroken over Gelert’s death, Prince Llewelyn buried his loyal dog and is said to have never smiled again.

Eventually, wolves became so evil stories of them hunting Christians around Christmastime were common. The Strasbourg sermon said wolves were “more savage about Christmas.” Some werewolves could only become wolves at Christmas and during the summer solstice. In the Abruzzi region of Italy, werewolves were encountered “about Christmas tide” on lonely country roads. In Latvia, thousands would gather at Christmas to attack humans and animals, wreck havoc, and drain beer casks. Werewolves in Livonia would gather at Christmas to transform for twelve days.

The belief suggests the Devil needed to work harder on this holy day. This might be why those born on Christmas Eve or on Christmas were thought destined to become werewolves. It could also be an older association with the Winter Solstice and the dark time of the year. In Wolves and Men it says Sioux call December’s moon “the moon when the wolves run together.” One Cherokee wolf song offers protection from frostbite, which further associates the wolf with winter.

Separated from western religions, it’s interesting that a Navajo traditional belief also says wolves can be evil witches. Many inexplicable events were once blamed on the dark practitioners, called wolves in their language. Wolf gall is said to be a powerful protective talisman against them.

![Past and present range of Canis lupus (edited by the author.) By Mariomassone - Own work, [1], Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=67537150](https://folklorethursday.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Grey_wolf_distribution_with_subdivisions.png)

Massive bounties were offered on individual wolves in the United States and Canada in the 19th and early 20th Centuries. These were the Outlaw Wolves. Many of them had elaborate backstories and villainous names like the Werewolf of Nut Lake, Rags the Digger, Lobo, King of Currumpaw, Queen Wolf, or Ghost Wolf of the Little Rockies. Many were said to have been born on Native reservations. One by one, each of them was hunted down and killed. Militia forces, using full battle drills, sometimes surrounded and attacked forests that were home to difficult packs. Victories would be celebrated with parades and medals. Wolf hunters became celebrities in North America, Crusaders protecting their fellow man and woman from the most evil creature that has ever existed.

In contrast, Middle Eastern lore sees the wolf as a benevolent spirit and as a protector of humans. When the Romans invaded North Africa, for example, a wolf drew a sleeping captain’s sword and carried it away. Wolves are also known to hunt and kill evil jinn spirits. There is an enmity between them. In Iraq, certain talismanic stones are believed to be jinn hiding from wolves. Some jinn have a wolf-like appearance – but they are not related, as wolves are their most bitter enemies. They are the good spirits that counter the jinn. This might be why Legends of the Fire Spirits says the last creature to die in the world will be the wolf.

Stories of the Wild Hunt – ghost riders – are told across much of Northern Europe. In many of them, dogs accompany the hunting party. A few mention wolves instead, such as Slovenia’s Volčji pastir – the Wolf Herdsman. Stories that name Odin specifically often describe him as lordly and aristocratic in appearance, accompanied by hunting hounds. It’s safe to assume, that the Northern god has dressed in fashion in order to make a specific impression, and that his hounds are actually his similarly disguised wolves, Geri and Freki. Perhaps, like the Valkyrie, they seek brave warriors to further fill the hall of Valhalla, as they make final preparations for Ragnarok.

The wolves swallow the Sun and the Moon and the stars disappear. Fenrir breaks his chain and the serpent rises out of the sea. The world is covered in water and the heavens are filled with the sounds of war. The gods and the heroic dead fall one after another, as blood stains all of the holy places and flows as free as glacial-fed rivers. Even the mighty one-eyed Odin falls in battle.

But straight thereafter shall Vidarr stride forth and set one foot upon the lower jaw of the Wolf. With one hand he shall seek the Wolf’s upper jaw and tear his gullet asunder; and that is the death of the Wolf. For Fenrir will die at the hand of Vidarr, Odin’s Son, the Silent God, the Avenger of the Gods. So the Prose Eda says anyways.

Sources

Aigle, Denise. “Transformation of an Origin Myth: From Shamanism to Islam.” 2008. PDF.

Black, Martha. Out of the Mist: Treasures of the Nuu-chah-nulth Chiefs. Victoria, BC: Royal British Columbia Museum. 1999.

Baring-Gould, Sabine. The Book of Were-Wolves [1865]. Denver, CO: Egregore Press. 2007. Digital.

Boas, Franz. Indian Myths and Legends From the North Pacific Coast of America [1895]. Vancouver, BC: Talonbooks. 2002.

Brodbeck, Simon, ed. Krishna’s Lineage: The Harivamsha of Vyasa’s Mahabharata. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. 2019. Digital.

Davidson, H.R. Ellis. Gods and Myths of Northern Europe. Toronto, ON: Penguin Books. 1990. Digital.

Fitzhugh, William W., and Susan A. Kaplan. Innua: Spirit World of the Bering Sea Eskimo. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press. 1982.

Hamel, Frank. Human Animals. New York, NY: Frederick A. Stokes Co. 1915. PDF.

Holmberg, Uno. The Mythology of all Races Volume IV: Finno-Urgic Siberian. Norwood, MA: Plimpton Press. 1927. PDF.

Knight, John. “On the Extinction of the Japanese Wolf.” Asian Folklore Studies. Volume 56, 1997.

Lebling, Robert. Legends of the Fire Spirits: Jinns and Genies From Arabia to Zanzibar. New York, NY: I. B. Tauris and Co. 2010.

Lopez, Barry. Of Wolves and Men. New York, NY: Scribner. 1970. Digital.

McIntyre, Rick. A Society of Wolves: National Parks and the Battle Over the Wolf. Stillwater, MN: Voyageur Press. 1993.

Plas, Peter. “Wolves and Death: An Assessment of Thanatological Wolf Symbolism in Western South Slavic Traditional Culture.” Academia.edu. 2012.

Sinn, Shanon. “The Celtic Werewolf.” Living Library. April 18, 2012. https://livinglibraryblog.com/the-celtic-werewolf/

Snorri, Struluson. Prose Edda. New York, NY: American-Scandinavian Foundation, Oxford University Press. 1916. PDF.

Summers, Montague. The Werewolf in Lore and Legend. New York, NY: Bell Publishing. 1966.

Thorpe, Benjamin. Northern Mythology, Comprising the Principal Popular Traditions and Superstitions of Scandinavia, North Germany, and the Netherlands Volume 2. London, England: Edward Lumley. 1851. PDF.

Trevelyan, Charles. Christianity and Hinduism Contrasted. London, UK: Longmans, Green, and Company. 1882. PDF.

Yokaigrove. “The Wolf’s Eyebrow.” Yokai Grove. January 24, 2017. https://yokaigrove.com/2017/01/24/狼の眉毛-the-wolfs-eyebrow/