Deep in that wildwood, below the lonely, mist-shrouded waters, in the faery realm that few mortals have ever seen, the Lady of the Lake heard someone endlessly, mournfully calling her:

‘Oh, my Lady! Oh, Nimue! Oh, my Lady!’

She guessed that Wizard Merlin had found his way to the lake again and was closing in on her. Hearing that he had discovered her own name – though she had taken much care to keep it from him – she knew that all was lost.

‘Oh Nimue!’ he called again. ‘Nimue, my Lady!’

His calls grew louder and more frequent. Because of them, she could not sleep or even rest. She heard him praying like a Christian, begging her to come to him; she heard him summoning her with weird, devilish spells. Though it angered her much to let him have his way, she could not allow him to destroy the tranquillity of the Great Forest. So she rose through the water and went to meet him upon the shore.

‘So, old wizard,’ she said, keeping her distance, not stepping onto the land where he might touch her. ‘I kept my promise. I gave your protégé the gift you asked for. What more do you want?’

This time he answered her plainly: ‘I want your love, Nimue.’

‘I cannot give it to you,’ she said.

‘Then I will wait until you can,’ said Merlin.

‘Your wait will last beyond eternity,’ she said. ‘And even then, you will never have me.’(Kerven: Arthurian Legends p. 22-3)

Sexual harassment in Arthurian Legend? Surely not!

When it comes to romance, wasn’t the whole Arthurian cycle defined by the concept of ‘courtly love’ – that peculiar medieval ritual which gave women unequivocal control? Typically, a young, heroic knight devoted himself adulterously to an older noblewoman trapped in a loveless marriage; he would unquestioningly obey her every whim and meekly accept all her rebukes.

However, there’s an episode in the most famous medieval Arthurian text, Thomas Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur, which challenges this convention. It concerns the sexual harassment of a beautiful woman by a besotted old man. Of course, the characters who take part in it are legendary inventions and larger than life; yet it’s a familiar situation that resonates with the experiences of many women throughout history. The victim’s brilliant solution depends on the existence of magic, so in practical terms it’s impossible for any real woman to emulate. Yet the principle behind it – turning the perpetrator’s own sinister methods against himself to bring about his downfall – is one that everyone can applaud.

The harasser under discussion is none other than the great wizard Merlin – astute confidante of King Arthur and supposed epitome of wisdom. And the subject of his unsavoury affections is the mysterious woman who presented the king with his fabled sword, Excalibur – the Lady of the Lake.

Their story is briefly told in the most famous medieval Arthurian book of all, Sir Thomas Malory’s 15th Century Le Morte d’Arthur:

Merlin fell in a dotage on … one of the damsels of the lake, that hight Nimue … But Merlin would let her have no rest, but always he would be with her …

And always Merlin lay about the lady to have her love, and she was ever passing weary of him, and fain would have been delivered of him, for she was afeard of him because he was a devil’s son, and she could not put him away by no means.

(Malory, Book IV chapter I)

However, Nimue turns his harassment to her advantage, persuading the wizard to teach her the secrets of his own magic crafts. She then allows him to follow her on a long journey – on condition that he never tries to enchant her. At the same time, she reigns in his lust by dangling the vague false hope that she will eventually allow him to have his will with her.

Nimue leads him on a long wild-goose chase through Britain and northern France, eventually arriving in Cornwall. There, says Malory, Merlin takes her to a rock that contains an enchanted treasure – where Nimue seizes her chance to escape. She persuades her pursuer to go within to fetch it, and then makes a spell to ensure he is trapped inside for ever:

Merlin shewed to her in a rock whereas was a great wonder, and wrought by enchantment that went under a great stone. So by her subtle working, she made Merlin to go under that stone to let her wit [learn] of the marvels there, but she wrought so there for him that he came never out for all the craft that he could do. And so she departed and left Merlin.

(Malory, Book IV chapter I)

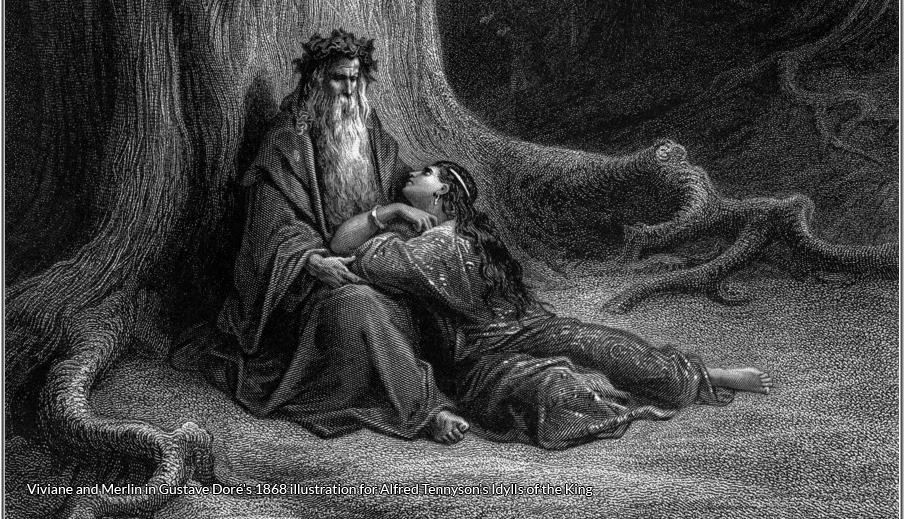

There is a similar tale in another 15th Century manuscript, Merlin or the Early History of King Arthur, which calls the Lady of the Lake Nimiane (other texts name her as Niniane or Viviane). It describes Merlin sleeping on her lap as she conjures up an enchantment of nine circles repeated nine times. This causes Merlin to dream that he is confined inside a strong, impenetrable fortress; and thus he mysteriously vanishes from the world.

What does all this tell us about the oral storytellers of the Middle Ages, who originally composed the wonderful body of Arthurian legends? Did they have a secret sympathy with the female cause, despite operating in a society where misogyny was the order of the day? What about their approaches to other female leading roles in the cycle, most notably Queen Guinevere (wicked adulteress? the real power behind the throne? tragic wronged wife?); and Morgan le Fay (evil witch? sagacious healer?). Were some of the ancient storytellers themselves women, presenting their own perspectives on male / female relationships? Or were they men simply trying to please the female audiences whose husbands paid them?

No doubt many scholars have already spent lifetimes of research and analysis trying to reach a viable conclusion … But what do you think?

Recommended Books from #FolkloreThursday

References

Kerven, Rosalind: The Enchantment of Merlin, in Arthurian Legends (National Trust Books 2011).

Malory, Sir Thomas. Le Morte D’Arthur, Volume I (first published by William Caxton, 1485. London: Penguin Books, 1969).

Merlin or the Early History of King Arthur (A Prose Romance), Vol. IV, translated and edited from the original English manuscript of c.1450–1460AD in the University Library, Cambridge by Henry B. Wheatley and William Edward Mead (London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co. for the Early English Text Society, 1899). Reproduced by Kessinger Publishing, Montana, 2007, chapters XIX, XXXII and XXXIII.