On the walls of a 300 BCE Etruscan tomb, a winged woman of dark and stern gaze flanks a door to the unknown. Her name is Vanth, and she often makes an appearance in violent scenes where one or more of the individuals depicted is on the verge of death. Is she the angel of Death, or perhaps Death’s messenger? If we have a closer look at the objects that she carries –a bunch of keys and a burning torch — we’ll realise that her role is that of a psychopomp, a liminal entity who guides the newly deceased into the Great Unknown: the Otherworld.

What we know about the Etruscans is largely based on tomb inscriptions and funerary art, since very few of their written records remain. This has only intensified their aura of mystery, a projection of the conspicuous Etruscan smile, secret and enigmatic, frozen on the lips of the funerary statues of those who have crossed the threshold and therefore know secrets beyond our reach.

Like the Greeks, the Etruscans believed in the existence of a Realm of the Dead, but the journey towards it wasn’t necessarily smooth. It would begin with the burial rites performed by the family: funerary urns depict a procession, similar to the Roman pompa funebris, but in this case there are demons mingling with the living. We don’t know whether they can be seen or sensed by mere mortals, but together they take the remains of the recently deceased to the door that separates this world from the Otherworld. It is at this point that the living must stay behind.

Representations of this door usually appear on the far wall of Etruscan tombs, always guarded by demons, part male or female, part monster or beast. Vanth, the winged demoness, is probably the most recurrent gatekeeper. Her keys open the gate, her torch lights the dark paths of the Underworld. The serpents around her arms reveal her liminal nature: snakes, always in contact with the earth, are frequent companions to chthonic entities.

Vanth is usually depicted with hunting boots, a short pleated skirt, and straps across her bare breasts – the attire of a Greek huntress. This is one of the reasons why she’s been suggested to have a Greek origin, perhaps inspired by the Erinyes, infernal goddesses of vengeance, also winged, but far more fearsome.

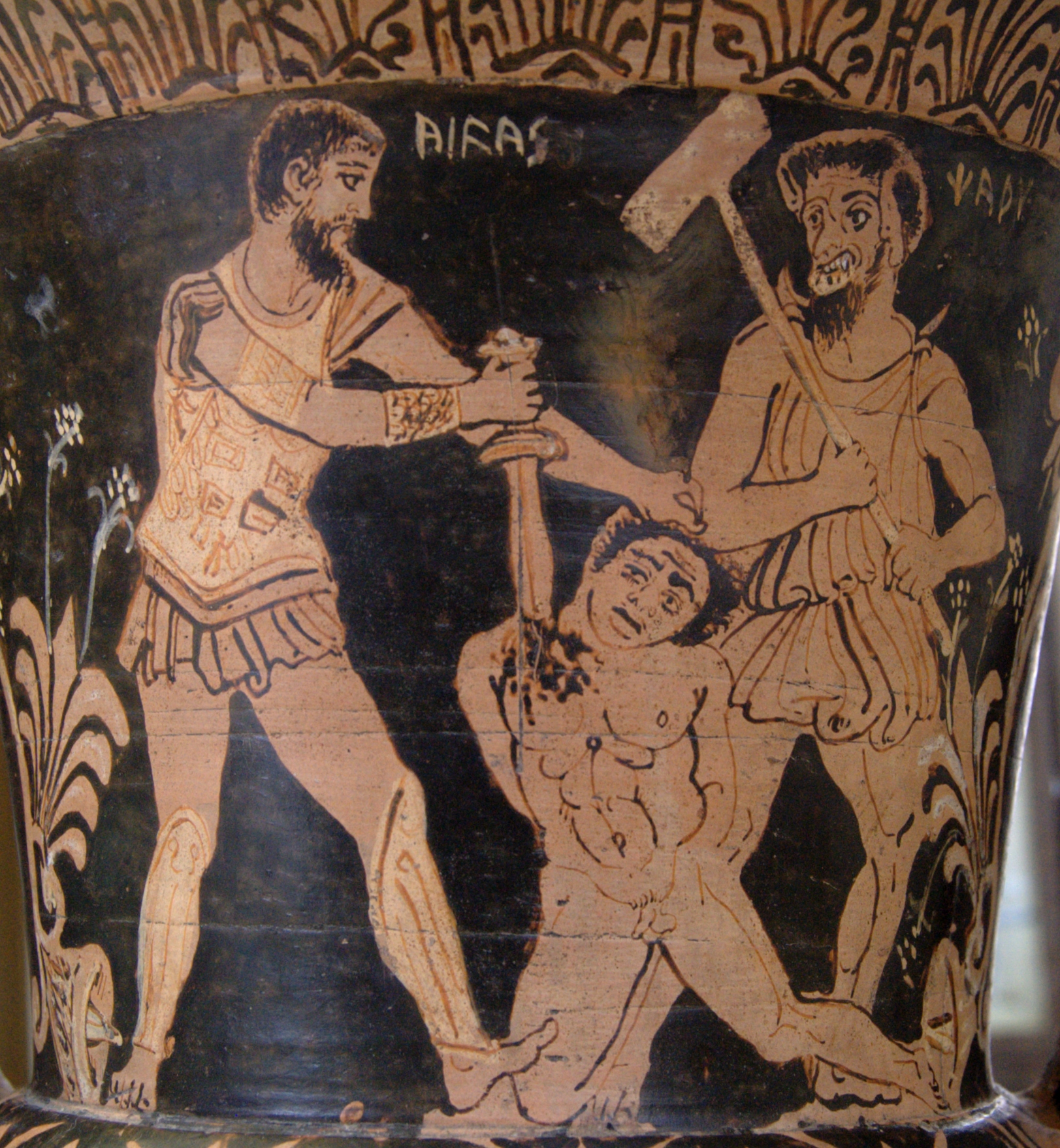

She is often accompanied by a less benevolent-looking hybrid figure, one with animal ears, pointed teeth, and snakes twined around his arms. Funerary inscriptions reveal his name is Charun – probably an adaptation of Charon, the Greek ferryman who begrudgingly escorts souls to Hades. Showing the decay of death in his bluish complexion, the Etruscan Charun is armed with a hammer, which he sometimes swings over a person’s head in a threatening manner. His brutish impulse may indicate that he isn’t merely a psychopomp, but also a protector of the dead, in charge of fending off evil spirits from the tomb.

Intriguingly, the doors guarded by Vanth and Charun may sometimes be half open, so we can catch a glimpse of the other realm. Some depictions, such as the sarcophagus of Hasti Afunei, are rather ambiguous, but it would seem as if the dead have come to open the door from the inside. These figures aren’t malevolent, they’re likely family members whose function is to greet newcomers and reassure them as they are about to enter the Great Unknown.

The most dangerous part of the journey would indeed start on the other side. Since Vanth appears escorting the dead in different ways (on horseback, wagon or chariot) it is reasonable to think that the transit probably had different stages. Depictions of sea monsters suggest that at some point or other the deceased would have to face a sea voyage. The rocky coastline painted on the walls of the Tomb of the Blue Demons (c. 400 BCE), where a legion of demons awaits by a skiff, seems to reinforce this idea.

Vanth and Charun might have been used as collective names for death demons in later Etruscan periods. We know the names of other creatures who show similar characteristics: the bearded Tuchulcha, whose gender is debated by scholars, has wings and a beak, and wields a mallet; the enigmatic Culsu carries a pair of scissors, perhaps to severe the soul from the body.

Whereas some of these entities could be more malevolent, there seems to be a general consensus in the protective roles of Vanth and Charun. The Etruscan Underworld was plagued by monsters (some of them as familiar as Cerberus, the three-headed dog who guards the entrance to Hades; Geryon, the giant warrior; or the Gorgons, whose gaze could turn a man into stone). All these perils, and those that we don’t know, given the scarcity of written sources, suggest that the presence of the stern Vanth and the brutal Charun were essential for the survival of the soul.

Sources:

Nancy Thomson de Grummond, 2006. Etruscan Myth, Sacred History, and Legend. University of Pennsylvania Press.

Sinclair Bell and Helen Nagy (ed.), 2009. New Perspectives on Etruria and Early Rome. University of Wisconsin Press.

Sinclair Bell and Alexandra A. Carpino (ed.), 2016. A Companion to the Etruscans. Wiley Blackwell.