There was a time when the living covered the mouths of their dead with a single coin before their final goodbye. The image of metal glinting over lifeless lips still makes us shiver. It has become a part of our collective subconscious, possibly because the ritual appeared in different traditions, and it survived, although marginally, until as recently as the 20th century.

The coins had a purpose: to allow the dead to pay for their passage to the Otherworld. In Ancient Greece, this was the realm of Hades, separated from the land of the living by five rivers. It was a perilous journey, and there was only one guide to take the recently departed to their final destination. His name was Charon, he of the keen gaze.

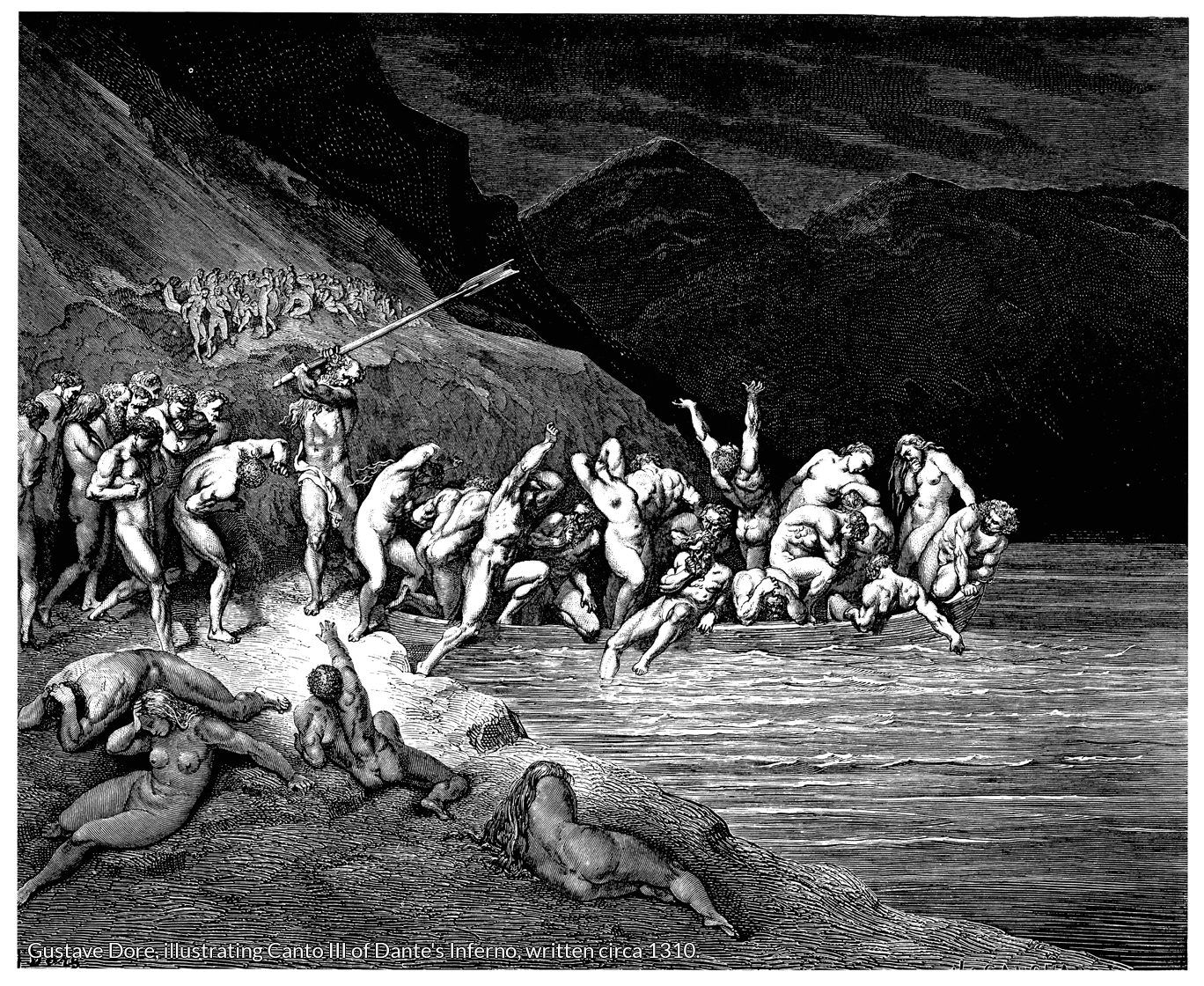

Inspite of his charming epithet, Charon was a fearful sight for those who found themselves alone in an unknown realm. Attic funerary vases of the fifth century B.C. depict him as a rough, ugly seaman. The Roman poet Virgil describes him as ‘a sordid god’ with ‘uncombed, unclean’ beard, and eyes ‘like hollow furnaces on fire’; Seneca mentions his ‘sunken cheeks’. Centuries later, Dante, drawing from Virgil’s work, presents him as a surly old man who refuses to take people on his boat. In a fresco in the Sistine Chapel, Michaelangelo portrays him as a corpulent creature, more beastly than human. But when we think of him now, we imagine a hooded, silent figure in a scene that seems taken from Arnold Böcklin’s most intriguing painting, The Isle of the Dead; Charon’s role as a psychopomp, a guide for souls in the afterlife, has determined his assimilation with the image of the Grim Reaper, the personification of Death.

Although the messenger-god Hermes escorted the dead to the river Acheron, once they reached it they were at the mercy of Charon’s moods. The unfortunate souls who didn’t have a coin (because their bodies hadn’t received a proper burial) were condemned to wander along the banks of the Cocytus, the river of lamentation, for all eternity.

The Acheron, or the river of woe, is, in fact, a real river in the Epirus region of northwestern Greece, one that flows through dark gorges and goes underground in several places, which may explain its long association with liminality. Since the river was considered a portal to Hades, its banks were the ideal location for the Necromanteion, the most important Oracle of the Dead in Ancient Greece. Odysseus visited it to contact the soul of the blind prophet Tiresias for advice on his journey, but he also suffered a series of terrifying visions involving torrents of blood, chilling screams and armies of wounded warriors.

We know little about the rituals that would allow the living to contact their dead at the Necromanteion: first, they would follow a special diet that probably included hallucinogens; they would then descend through underground corridors and cross three gates that replicated the ones in Hades and that took them to the dark chamber, the most secret place of all. It was here that the dead would come to speak, as shadows fluttering over the dimly-lit stone walls. But no matter what they had seen, pilgrims couldn’t reveal it to anyone, or fearful Hades, the lord of the Underworld, would take their lives in retaliation.

The geography of the Greek Underworld is fascinating, and its knowledge was fundamental to Antiquity’s mystery religions. We know most of these details from totenpässe, the so-called passports of the dead, thin gold foil pieces found in the mouths of skeletons, inscribed with details to navigate the other realm.

The most important instructions from these totenpässe are those regarding Lethe, the river of forgetfulness. According to Ovid, it flowed through the cave of Hypnos, the god of sleep. Lethargic and groggy, the dead were asked to drink from its waters, but this would make them forget their earthly lives. Mystery religions noted that there was another river from which souls could choose to drink if they were wise: Mnemosyne, whose waters would make the initiated remember their past existence and achieve omniscience, thus breaking the cycle of reincarnation.

The remaining two rivers were Phlegethon (the river of fire, which didn’t consume anything within its flame) and Styx. After crossing the latter, the souls would finally arrive in Hades. But the perils of the journey didn’t end here: Anacreon warns us that ‘Hades’ hall is horrifying, and the passage there is hard’. Worse: it is decided that ‘whoever ventures there may not return’. Welcomed by the monstrous dog Cerberus, who allowed no one to leave, the souls would have to confront three judges: Rhadamanthus, Minos and Aeacus, who would decide on their destiny based on their deeds during their human existence. A positive sentence would allow them to go to the Elysian Fields, but a negative one might bring the eternal torment that Sisyphus or Tantalus endured.

The myth of the ferryman, embodied in Charon’s oboli and totenpässe, reflects a universal constant: the belief that the journey to the Otherworld is a perilous adventure, so the presence of a psychopomp, even when he’s belligerent, bad tempered and unreliable, is crucial to the fate of our souls.