If you ever stay in a Spanish village, know that there are some things you mustn’t do after night falls: Don’t walk alone into the forest. Don’t accept gifts from strangers. And if you see light coming from a church, don’t walk in – certain rituals should never be interrupted.

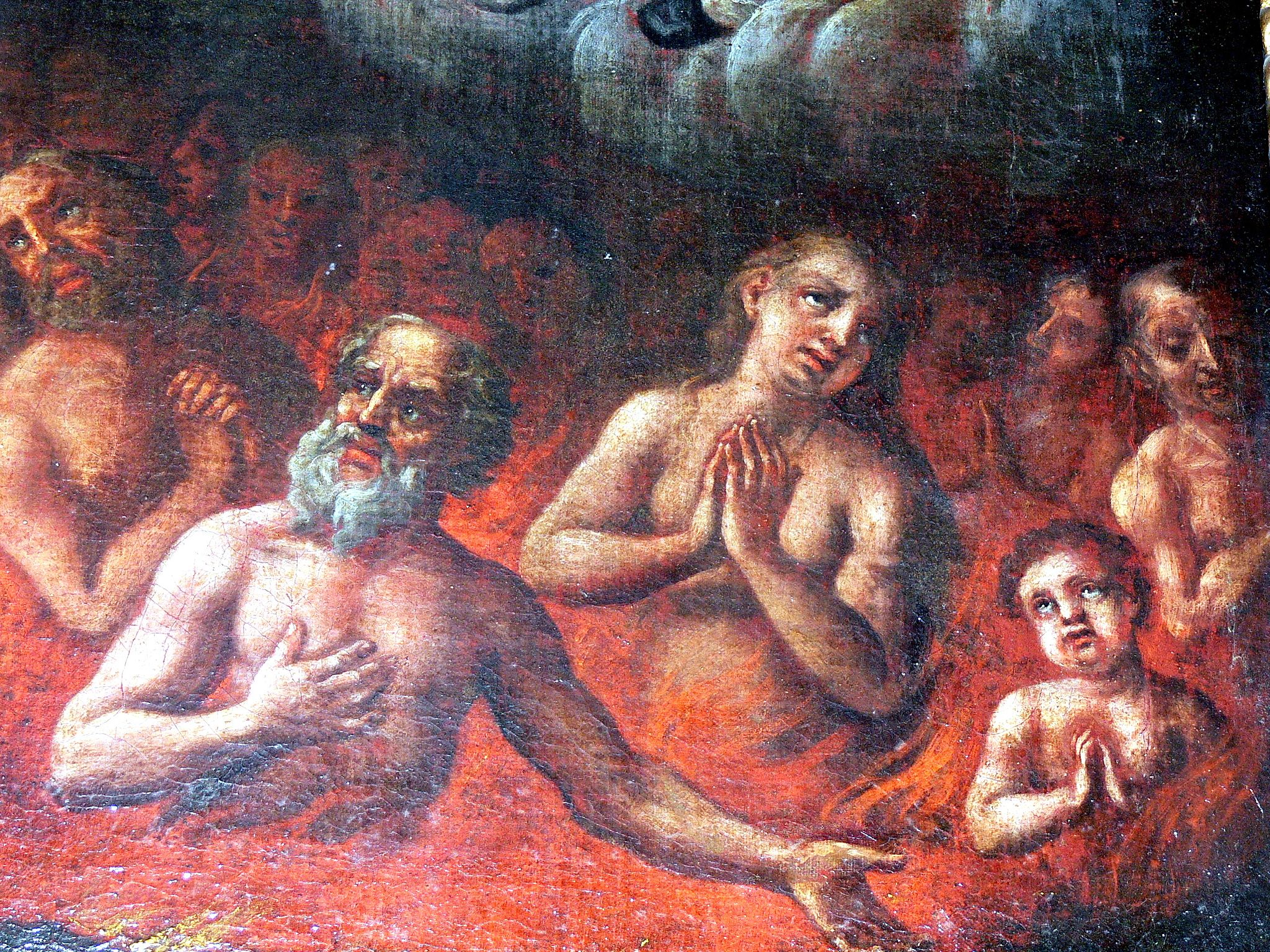

In rural Spain, the night still belongs to the ánimas, the spirits of the dead who didn’t go straight to Heaven or Hell. Stuck in the liminal realm that Catholics call Purgatory, these souls can sometimes be seen by the living, but an encounter with them may prove fatal.

The Holy Company

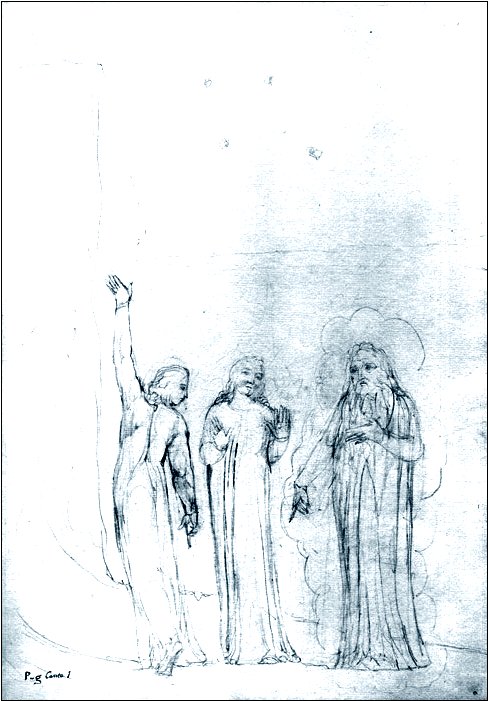

When the ánimas travel together they’re known as the Santa Compaña (the Holy Company). If you smell wax or see a row of flickering lights in the distance, you’ll know they’re near. Those who’ve seen them describe a procession of hooded figures dressed in black, holding candles. Perhaps their leader carries a wooden cross or a bell, perhaps they’re mumbling a litany. But their appearance shouldn’t fool you: they aren’t just a group of devout parishioners. If you talk to them or hold the candle they offer, you will see your own flesh decay and fall from your bones. Only then will you realise that this is what they hide under their hoods, but it will be too late: in every tradition, folklore tells us that whoever reaches the other realm must remain in it forever – so whoever talks to the Compaña will be condemned to join their procession for all eternity.

Staying indoors after dark won’t necessarily protect you from them. The Compaña may knock on your door, which means someone in your house has been given hours to live; or you may glance through the window to find them marching around a neighbour’s house, a sign that someone in that household will die soon. Even though their arrival is an omen of death, these spirits aren’t always evil: they also appear to escort the dying from their deathbeads, in the difficult passage to the other side.

Every village has its own procession, formed by the souls of the parishioners who still need to purge their sins before they can reach the glory of Heaven. Those locals who’ve seen it often recognise familiar faces under the black hoods. There are some protective measures to avoid being snatched away: standing inside a circle of salt, offering breadcrumbs to the ánimas, throwing them a black cat, or stepping onto the base of a cruceiro, the cross signs that were placed at crossroads to protect travellers from evil spirits.

The mass of the ánimas

The countryside isn’t always a peaceful place, and churches aren’t always safe havens. Once the sun is set, those who wander rural paths may see a light coming from inside a church or a chapel. On entering they will discover that a mass is being celebrated. If they decide to join in, at some point they may recognise some of the parishioners, faces they haven’t seen in years, or even decades: the mass of the ánimas is a ghostly assembly, where the parishioners and the priest are dead, praying for their poor souls trapped in Purgatory. But interacting with them, holding a Bible or taking holy water might mean never returning to the world of the living.

A prayer for the ánimas

Aside from their penance, the only way the ánimas can achieve redemption is through alms and prayers, for which they need the intervention of the living. Relatives and friends pray for their loved ones, but it is also frequent to find prayers “for the souls in Purgatory”. These tend to work as a little exchange: “I will pray for you if you do something for me”. Some people request the protection of the dead, so they don’t die in their sleep; some ask to be woken at a certain time in the morning to avoid missing an important event (in this case, the sleeper will hear an otherwordly voice calling her name, and perhaps see a shadow by the side of her bed).

These “collaborative efforts” show the living and the dead working together amicably, for their mutual benefit. However, as we’ve seen with the Compaña, you can’t trust all souls in Purgatory. Most people distinguish between ánimas blancas or ánimas benditas and ánimas negras. The latter are said to be more powerful, their interventions almost miraculous, but they are ultimately malevolent and, should something not go as planned, their retaliation will be fearsome. Those who light black candles to ask the ánimas negras a favour are often regarded suspiciously by others, much as if they were engaging in black magic. Some whisper tales of revenge and torment, where a friend or relative has been driven to insanity by invisible presences.

Ánimas and fairies

The similarities between the ánimas and Fairyland aren’t a coincidence. Both stem from the introduction of the doctrine of Purgatory in the 13th century, the dogma that triggered the Lutheran reform. This wasn’t entirely a new belief either: it fitted with ancient traditions that acknowledged the existence of a liminal realm where suicides or warriors dwelled. This realm wasn’t as remote as Heaven or Hell, but closer to the world of the living; its borders were thinner, and therefore, the souls who inhabited it were easier to see – and easier to summon. The evolution of this belief in Spain, shaped by superstition, Catholic imagery and Paganism, is fascinating.

Recommended Books from #FolkloreThursday

Carmelo Lisón Tolosana. Brujería, estructura social y simbolismo en Galicia. 2004.

Constantino Cabal. Los dioses de la muerte. La mitología asturiana. 2008.

Aurelio de Llano Roza de Ampudia, Del Folclore Asturiano. Talleres de Voluntad. 1983.