Deep below the depths of the ocean, strange things lie. Hidden in the dark within sea caves, your fears reside. Creatures from below, from myth, legend and lore, stalk our nightmares, give us chills but we are always wanting more.

In my last article, I explored some of the tales and the folklore behind our most famous pirates, getting to the core of what makes these enigmatic characters so interesting. However, these characters only bring so much intrigue thanks to a great supporting cast: the creatures that stalk their lore and legend.

Below the thunders of the upper deep;

Far far beneath in the abysmal sea,

His ancient, dreamless, uninvaded sleep

The Kraken sleepeth: faintest sunlights flee

-Alfred Tennyson ‘The Kraken’ 1830

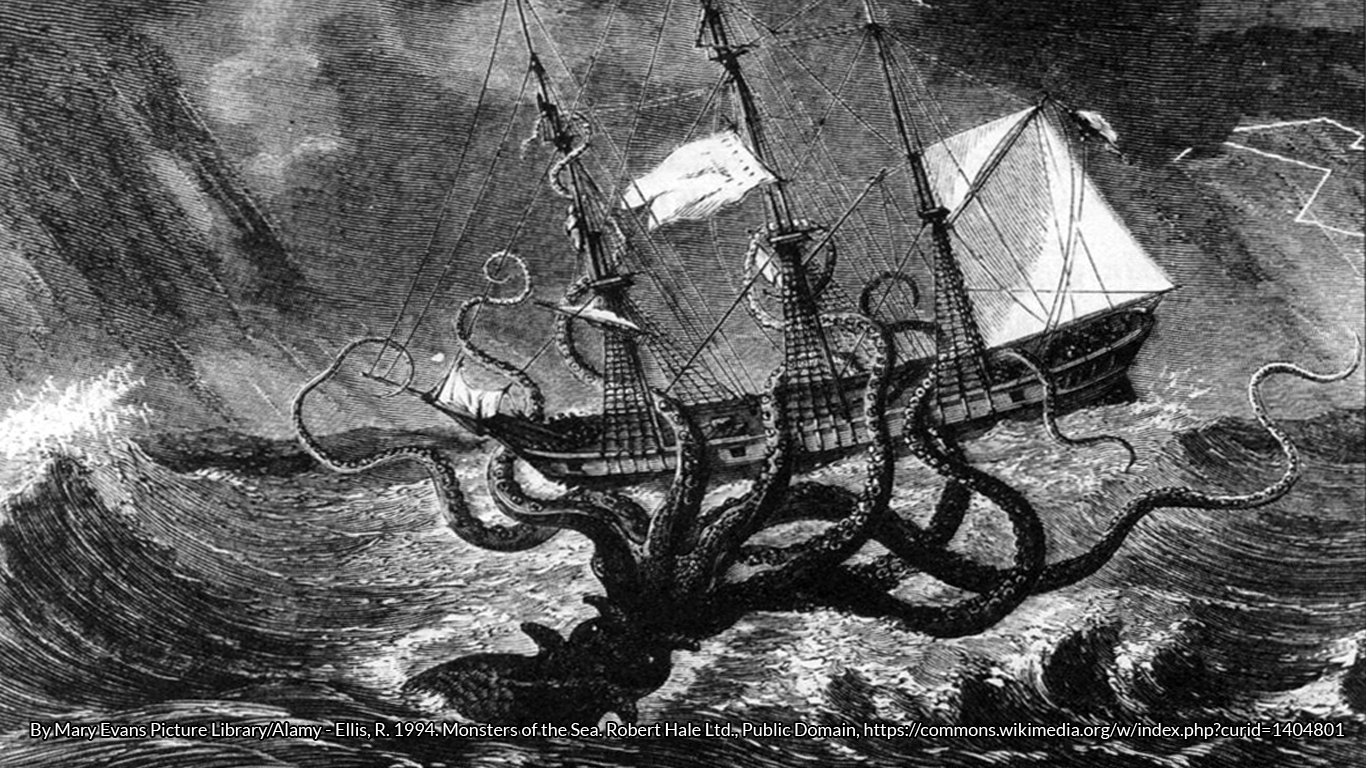

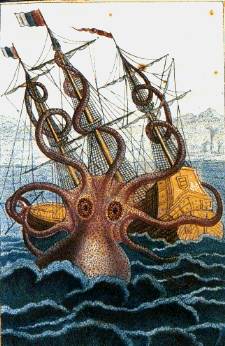

Squid-like in appearance, the Kraken is said to stalk the icy waters around Iceland and Greenland. A popular figure in modern sealore but where did the legend start? Its origins can be traced back to an ancient Norwegian saga titled ‘Örvar-Oddr’. The first reference comes from a 13th century rewrite, in which the crew of the heroes ship firstly mistakes a whale-like creature known as lyngbakr, for an island. Several of the crew drown after lyngbakr returns to the sea with them on its back and then sail through the jaws of the hafgufa, the nordic word for Kraken. It is described as such:

It stays submerged for days, then rears its head and nostrils above surface and stays that way at least until the change of tide. Now, that sound we just sailed through was the space between its jaws, and its nostrils and lower jaw were those rocks that appeared in the sea, while the lyngbakr was the island we saw sinking down.

-Translated from Örvar-Oddr circa 1225

The very name we use today has its roots in Norwegian, from their word krake meaning an unhealthy animal or twisted. This is very apt seeing as, with its many arms, it twists itself around the unfortunate ships of its victims before dragging them down to meet their fate below the waves. In German, the word krake means octopus and is used to name the creature that is often depicted and described as octopus or squid-like. It also shares many similarities with a creature from the Greek epic, The Odyssey, but, despite popular belief, the Kraken is never mentioned in Greek or Roman myth.

Carolus Linnaeus, the father of modern taxonomy, classified the Kraken as a cephalopod and even gave it a Latin name, Microcosmus marinus, in 1735. A Norwegian scientist from the 13th century concluded that there was a pair of Kraken, yet they were unable to mate.

Such is the interest for this creature, that it has found itself into popular culture, capturing our imaginations, tangling our dreams in its many squid like arms. It was written about by Alfred Tennyson (see above), Herman Melville in his seminal classic, Moby Dick, and starred in Jules Verne’s classic, Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea. The Kraken has even been depicted in modern times, in movies such as the Pirates of the Caribbean and even appearing on bottles of spiced rum, which also bears its name.

Another staple of sea legend and myth are mermaids. These elusive creatures stalk the waters, beckoning sailors with their haunting songs, causing the ships to crash upon the rocks, dooming the men to sleep forever in Davy Jones’ locker. Yet these beauties of the deep are well known, and rightfully feared; selkies, however, less so.

These gentle creatures are found in the seas off Scotland, Ireland, Iceland and Greenland, if the tales are to be believed. Taking their names from the Orcadian dialect word for ‘seal’ (an Orcadian being a native of the Orkney islands of Scotland), these creatures are just that: seals. But wait, they are no ordinary cute bundle of fur and blubber. These creatures are said to be related to the much feared Finnfolk, shapeshifters from the deep, who stalk the seashore for unsuspecting humans to take back to the depths for a life of servitude. Selkies, however, are believed to be more benign. These creatures frolic in the waves in seal form, beaching themselves on the rocks to shed their seal skins and dance in their human forms, within the moonlight, both men and women.

Many stories are told of how men have withheld the skins of these beauties and forced them into marriage only for them to finally return to the sea, their children following many years later. A gentle race, you may think, peace loving and kind — but it seems we may be wrong. Dennison, a folklorist from the 19th century, believed that these tales of the selkie-folk had their origins alongside those of the vicious Finnfolk and had been merged with tales of mermaids and seals to create ‘a wholly different race of beings from the Finfolk’ (Dennison).

It is not all about the seductive female selkies in these tales though. The male selkies are said to be somewhat predatory in their nature, coming to shore to seek out lonely fish wives, to lie with them, and be one. Lonely women have also been known to summon the male selkies by sending seven tears to sea.

The sea holds many mysteries, even to this day. It is sometimes thought that we know less about the oceans of our own planet than we do of our silent satellite that orbits our world, bringing the tides and reflecting the sun’s rays back at us at night so we may see in the inky blackness. Who truly knows what lies beneath our waters? Even this year a large, strange, unidentifiable carcass was washed up in the Philippines. Maybe the Kraken does stalk the deep, watching and waiting. Perhaps the selkie people do quietly keep watch of our northern shores, who knows? Until then, they live on through the stories we tell, stories as old as language and as constant as the tides.