The fairy-tale witch is a compelling, frightening, and reliable stock character in our contemporary society. Mention “witch” and the hag of fairy-tale picture books for children comes to mind far more frequently than any other, more nuanced image. As fairy-tale scholar Jack Zipes puts it, “[w]e use the word [‘witch’] ‘naturally’ in all Western countries as if we all know what a witch is”. The witch of our most well-known and well-loved fairy tales is, however, a far more versatile figure than the one-dimensional crone with a wart on her nose and a cartoonish cackle on her lips. In this article, we will explore the witch of the Grimms’ fairy tales in her many guises, from mother to monster, from helper to heroine.

The witches that appear in folklore — in fairy tales, legends, and other folk narratives — are often deeply ambiguous. Rarely are they purely good or evil. Consider, for example, the famous Russian folkloric witch Baba Yaga. In some tales, she is an evil monster… in others, she is the main character’s only hope — “she is not just a dangerous witch but also a maternal benefactress”. Witches are liminal, creatures of thresholds and becomings who resist simple binaries. They frequently have close ties to the natural world. They are associated with healing and knowledge as often as they are with dark magic, but, in either case, “[w]itchcraft is all about power” (Reiti 3). Witches of folklore invite change and galvanize transformation.

In 1812, the brothers Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm released the first edition of their Children and Household Tales. Though they revised the tales many times over the next four decades, their fairy tales were always populated with witches and witch-like figures. Though we readily acknowledge that Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm themselves did not share today’s expansive view of what witches can represent, here are just a few of the vibrant and varied roles that witches play in the brothers’ book of fairy tales.

Witch as Monster

The fairy-tale witch that almost certainly first comes to mind is that of the monstrous witch. She is the hooked-nose, cackling, long-nailed nightmare of haunted forests, stolen children, and the spookiest of Halloween dolls. This is the cannibalistic witch in the Grimms’ famous fairy tale “Hansel and Gretel” who builds an irresistible house out of cake and sugar to lure starving children into her clutches. She is, undeniably, a monster: she is an incarnation of uncontrollable hunger in a world where starvation was an all-too-real possibility (Tatar 229-232).

While the witch of “Hansel and Gretel” is beyond redemption (again: cannibalism!), we do want to note that “monster” does not have to mean “evil.” “Monstrousness” is frequently attributed to anyone who challenges social order or ruptures the fabric of the expected. A witch who is deemed to be monstrous may indeed be violent or cruel, but she may just as easily be kind or neutral — monstrosity is often not about the actions or character of the one deemed to be “monstrous” but about the way that others perceive her. In “Mother Holle,” another fairy tale in the Grimms’ collection, the witch seems frightening at first, with huge teeth, but turns out to be a kind figure who rewards those who help her.

Witch as Mother

It must be said that parents are rarely positive figures in fairy tales. When they aren’t dead, they are often neglectful, and they can even be malevolent or murderous. The Grimms’ tales feature many terrible witch-mothers, and perhaps the most famous are the stepmother of “Snow White,” who is knowledgeable in certain magical arts and attempts to poison her stepdaughter, and the witch of “Rapunzel,” who takes a child in payment for stolen vegetables from her garden, blinds Rapunzel’s prince, and casts her out into the wilderness alone and pregnant.

However, there are positive versions of witchy motherhood to be found in the collection, as well. In “The Goose Girl at the Well,” a witch takes on the mothering role with fierce protectiveness and compassion, guiding the young princess in her care and helping her to better her life.

Witch as Helper

Witches can offer aid and guidance as often as they hurt or hinder. A fascinating instance of the witch as a helper figure occurs in the Grimms’ little known tale “The Three Spinners,” parallels the much more famous “Rumpelstiltskin.” In “The Three Spinners,” three strange, witch-like women come to the aid of a young, lazy girl who hates to spin. Instead of requiring jewelry and her firstborn child as payment for their help, the women ask only to be invited to her wedding and to be called her aunts. Instead of fracturing family, as Rumpelstiltskin would do, the spinners help to strengthen and reinforce community ties. In the end, they even help ensure that she never has to spin again by convincing her new husband that spinning is what made them ugly!

Witch as Lover

At first brush, “Frau Trude” might seem to be a story about another monstrous witch. After all, it appears to be a cautionary tale about a girl who seeks out a witch and is transformed into a log and set on fire by that witch for her trouble. On the other hand, folklorist Kay Turner has argued that the tale might instead be interpreted as one in which the young girl seeks out Frau Trude because she is drawn to her, a feeling that the waiting witch reciprocates. In this reading, the girl’s transformation into “fire” is a metaphor for her sexual awakening, her “flames of passion” (Turner 261), and the tale becomes a queer love story of two outcasted women finding each other (Turner 2012).

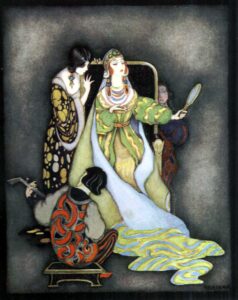

Witch as Princess

If a witch can play so many of the traditional roles for women in the Grimms’ fairy tales, the question must be asked: can a witch also be a princess? We would argue yes. In the tale “All Kinds of Fur,” the princess protagonist is distinctly witch-like – at one point in the text, she is even called a witch! She is not afraid to be ugly, even gender-less, while wearing her furs, she is skilled in witch-associated crafts like cooking, and she somehow manages to put three enormous ball gowns and three golden objects into a nutshell! While we don’t endorse the simplistic statement that fairy-tale princesses are generally passive, the princess of this story moves through her tale with a versatility and ambiguity that suggests a kinship with the witch. She is, after all, “largely responsible for her own transformations” (Yocom 104). Thus, yes, we contend that witches can also be princesses.

The witches of the Grimms’ fairy tales occupy a far more diverse set of roles than is frequently assumed. By turns dangerous and kind, hideous and beautiful, outcasted and social, they are often at the heart of their tales, a perfect reminder that fairy tales are never as simple as they first seem.

References & Further Reading

Rieti, Barbara. Making Witches: Newfoundland Traditions of Spells and Counterspells. Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2008.

Tatar, Maria. “Introduction: Tricksters.” The Classic Fairy Tales, edited by Maria Tatar. 2nd Ed. New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 2017. 229-235.

Turner, Kay. “Playing with Fire: Transgression as Truth in Grimms’ ‘Frau Trude.’” Transgressive Tales: Queering the Grimms, edited by Kay Turner and Pauline Greenhill. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2012. 245-274.

Yocom, Margaret R. “’But Who Are You Really?’: Ambiguous Bodies and Ambiguous Pronouns in ‘Allerleirauh.’” Transgressive Tales: Queering the Grimms, edited by Kay Turner and Pauline Greenhill. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2012. 91-118.

Zipes, Jack. The Irresistible Fairy Tales: The Cultural and Social History of a Genre. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2012.

Grimm Tales Mentioned:

“All Kinds of Fur,” “Frau Trude,” “The Goose Girl at the Well,” “Hansel and Gretel,” “Mother Holle,” “Rapunzel,” “Rumpelstiltskin,” “Snow White,” and “The Three Spinners.”