As a symbol of romance and love, the stylized heart is widely recognized while St. Valentine is regarded as one of the patron saints of lovers. It wasn’t until the Middle Ages – roughly in the 14th century — that the symbolic heart took its now familiar shape. About that same time, the famous English poet Geoffrey Chaucer recorded St. Valentine’s day as a day of romance in his 1375 poem titled “Parliament of Foules”. In it he wrote, “For this was sent on Seynt Valentyne’s day / Whan every foul cometh ther to choose his mate.”

But what about the more unusual practices concerning the human heart, both in form and in practice?

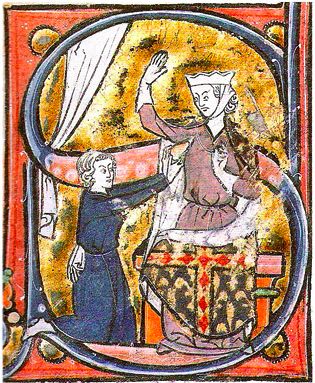

During the Middle Ages, the human heart was literally considered as the receptacle that recorded a person’s life. All good deeds and bad would be recorded therein providing a type of a record. Presumably the record would be revealed and taken into account at the Gates of St. Peter on Judgement Day. This Middle Age belief is thought to have originated in much older customs, pre-dating Christianity. As in the age of the Celts and prior to the Middle Ages, human hearts were cut out both for sacrifice and representing the ultimate symbolism of conquest. Such practices included cutting out an enemy’s heart upon a battlefield.

In the Middle Ages, however, hearts were removed from bodies for ‘newer’ reasons. During the Crusades, noblemen often ended up dying halfway around the world. With the emergence of the human heart as a centre for romantic notions, it was also attributed with a sense of emblematic loyalty and honour. As the reasoning of the time went, if a Crusader perished far from home, it would be natural that his final request might reasonably involve removing the heart from his body for return to his ancestral seat. Therefor while his mortal body may be entombed in a foreign land, his heart – that most important organ- would be returned to the location of his heart’s desire (i.e. his family estate, parish or such endowment).

For “practical and hygienic reasons, such corpses were dismembered prior to boiling in wine or water. The viscera were often burned at the place of death, but the heart was then transported home.”1 Heart removals were usually entrusted to cooks or butchers who were deemed “appropriate” for such travails. Depending upon whatever conveyances were at hand, the hearts were often carried in special containers and packed in wine and spices. Those additives were presumably for preservation and to keep the organ from becoming too rank and offensive.

Examples of churches that may contain Crusader’s hearts include the Leybourne and Fordwich churches, both in Kent, England. According to one parish record,

“In 1270 Sir Roger set off with Edward for the Holy Land, but was probably sent back en route through ill health, and died in France. His heart was sent home and placed in the left-hand [sic] casket of the Heart Shrine in the north wall of the church…”3

The practice of ablation mainly involved the hearts of men – but female saints proved the exception to the rule. While not speaking solely of hearts, the trade of relics was in full swing. Saints’ bodies were often dissected for veneration at various cathedrals scattered throughout Christendom. This dissection often occurred several years after death, once the process of beatification began. And, of course, there was a financial incentive behind this custom. When bodies required two or more separate burial locations, additional monuments generated income and the sale of relics provided a method of enrichment for individual orders or churches.

On a less inspiring note, traitors also had their hearts removed, apparently for punitive or cautionary reasons.

All of which goes toward proving, in the Medieval mind, there were good hearts and there were bad hearts. Good hearts were filled with light, purity and honourable intentions. Bad hearts were malicious and filled treachery.

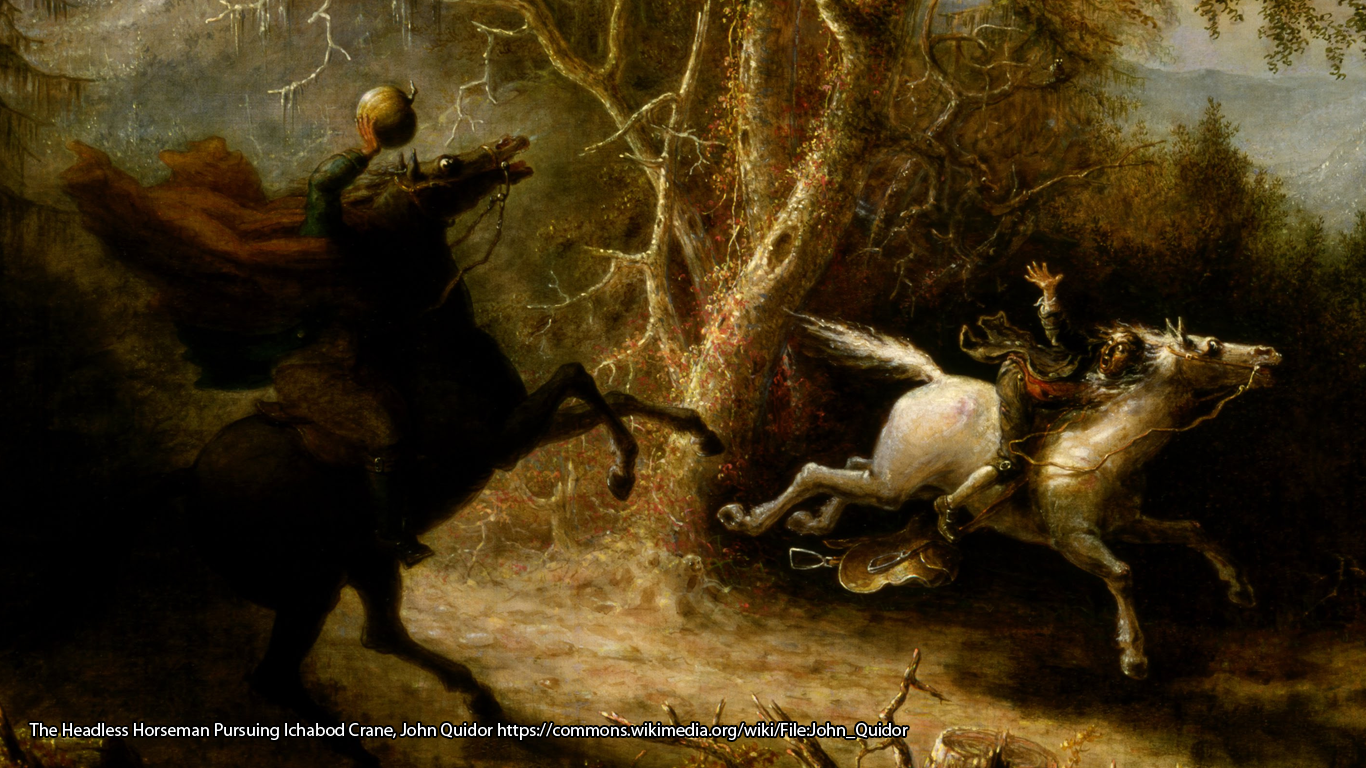

All of which is great fodder for folklore, fairy tales and ghost stories.

An Oxford ghost story is attached to the heart burial of William King the principal of St Mary Hall (prior to its merger with Oriel College in 1806). The heart was supposedly contained within a silver or marble vase near the north wall of the chapel. According to one Reverend Phelps, Provost of Oriel College, he was haunted by the tapping of the heart of William King. Apparently Phelps, when living in St Mary Hall, had a bed which abutted the wall behind which the vase containing the heart was recessed. On asking the next occupant of the room about the tapping Reverend Phelps was told it was the beating of King’s heart in the vase.4

Such stories, no doubt, may have influenced Edgar Allen Poe in the Tell-Tale Heart.

As to form, however, nothing takes the place of a witch’s heart. A variation on the Georgian open-heart brooch was the witch’s heart. In these pieces, the tail of the heart twist to one direction (usually the right). This style gained popularity in Scotland in the 17th century and was named “Luckenbooth” after the closed booths in Edinburgh where they were sold. Witch’s hearts were initially worn to protect loved ones from evil spirits. Tiny witch’s hearts were pinned to baby’s blankets to ward off dark forces.5 Such emblems are historical in their own right. As to whether people take this as “dark” history, it is fascinating, nevertheless.

As Valentine’s Day comes around, spare a passing thought for that ubiquitous red heart that has come to symbolize the event. Historically speaking, there is a lot more than is at the surface for that emblem of love.

References and Further Reading

1https://www.history.com/topics/valentines-day/history-of-valentines-day-2. Retrieved December 24, 2019.

2 http://web.prm.ox.ac.uk/rpr/index.php/objectbiographies/75-human-heart-in-a-heart-shaped-cist-18845718.html. Retrieved December 20, 2019.

3 https://www.leybournechurch.org.uk/history. Retrieved December 20, 2019.

4 Magrath, J. R.Notes and Queries.12.S.I.March 4, 1916. http://web.prm.ox.ac.uk/rpr/index.php/objectbiographies/75-human-heart-in-a-heart-shaped-cist-18845718.html. Retrieved December 20, 2019.

5 Jacobs, Barbara Michelle. https://www.bmjnyc.com/blogs/blog/52481349-witch-s-heart-jewelry-and-other-antique-heart-jewels. Retrieved December 23, 2019.