The best folk stories live in the geography of the mind, grow in maturity alongside your soul, and so it is for me with the stories of selkies.

I grew up in Evesham, far the sea. At the age of fourteen, almost out of childhood, but still not yet a woman, I heard on the radio a story, by Kevin Crossley-Holland, about a creature called a selkie.

This is me, reading the story on YouTube:

The story is The Sea Woman and comes from the Orchard book of British Folk Tales. I was so moved and impressed by this story that my father ordered a copy of the book for me, hardback, illustrated, beautiful. I can still remember the feeling of joy when he handed it to me. It seems like such a small gift in these times when books seem so available to me, but we had so few books when I was a child. They were a luxury. In many ways they still are.

I want to take you first for a walk now, with me, over the hill and far away. It is fitting that today is ‘an empty, oyster and pearl’ day, for that is how The Sea Woman begins.

I may have grown up landlocked, but for the past 25 years I have lived in a small cottage beside the sea.

Here time is different.

I measure my days by the coming and going of the light, my nights by the passage of the stars across the night sky, and time by the swelling and shrinking of the moon and the tides. Years come and go with swallows and wheatears, seals and lapwings. And if you listen, the stones tell you stories.

The first story that I found in this land where I live was The Seal Children, and as we walk the path to Maes Y Mynydd where the story is set, my mind wanders back through selkie stories. For that one story, accidentally overheard, led to a fascination with these mythical creatures. My child self could not understand how a man could snatch at the skin of the seal woman and keep from her this thing she needed, saying: ‘I love you, and so you MUST live with me,’ and then hide her skin and keep it from her. My child self knew that this was wrong. And as I moved into adulthood and found Women Who Run With the Wolves and read Sealskin Soulskin, a story in this book, I learned that it is always good to keep your soul close, not give it away.

People of the Sea by David Thompson taught me more, gave me different interpretations, and taught me also that there were selkie men in the world as well as women. I loved this book, and somehow left my copy on Ramsey Island where I stayed for a few days while working on The Seal Children. On a night when the moon shone full I sat on the cliffs listening to seals singing, haunting soul song. It seemed fitting that the book stayed behind.

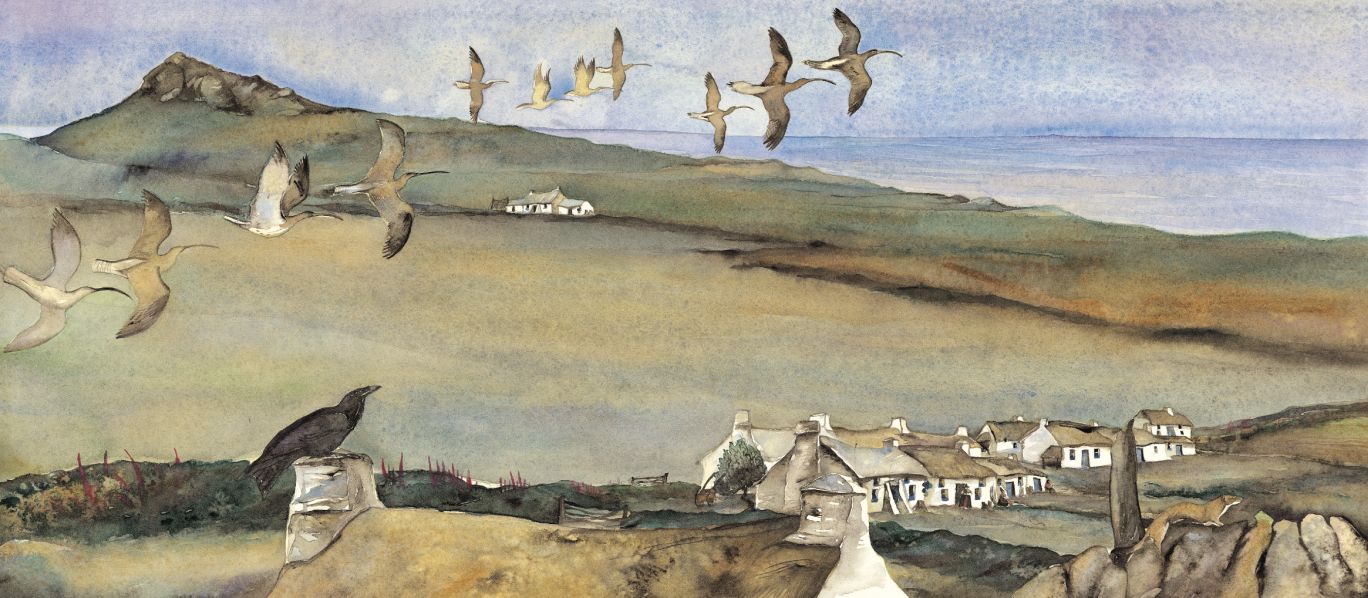

The path to the old village is overgrown now. Once it was trodden by many feet. Once many people lived here. These tumbled walls were homes. Small cottages like many that still stand. Country cottages. But do not get the wrong idea. This village that clings to the side of the land, snugged low against the winds was no paradise. Life here was hard. The cottages were tied cottages belonging to the farmers who owned the land and the people who lived in them worked hard.

Whenever I walk here I try to imagine what it was like. The homes were abandoned at the turn of the 20th century, but few lived there then, maybe six people. People were poor. They worked the land. Even the children would pick rocks from the fields, pull weeds, labour for the landlords. With no money to pay for doctors life could be short.

The peace of this day helps with time travel as no sounds can be heard but the voices of birds, stonechat, buzzard, chough and raven. When Maes y mynydd was inhabited there were no cars, no planes to scar the sky, boats were steam, sail or pulled by oars.

The main ruin here, when I first walked these paths 25 years ago, still had an intact chimney fawr. The weight of stone was held up by a great piece of ships timber, complete with tunnels from toledo worms. My children would stand under the chimney, looking up at the light and the cats would wander through the ruins. Time has taken its toll, tumbled the stones, opened holes in the walls, tumbled the lintels. You can still see where the well was, still mark where the gardens separated from the fields, still see the small stone animal pens and in places medieval strip fields.

It was walking here one day, years ago, and the landscape all fog, bringing focus in close but sounds strange in air that the story of The Seal Children came to me. As I walked the dripping ruins I could hear the seal mothers singing to their pups on the stone beach, across the heather moor.

I wanted to write a book about fractured families. A book that would give children the space to talk about their feelings, not just the children who were experiencing this, through their own lives but others around them, for such fractures ripple out. A book about relationships. And so Ewan’s story settled in my mind.

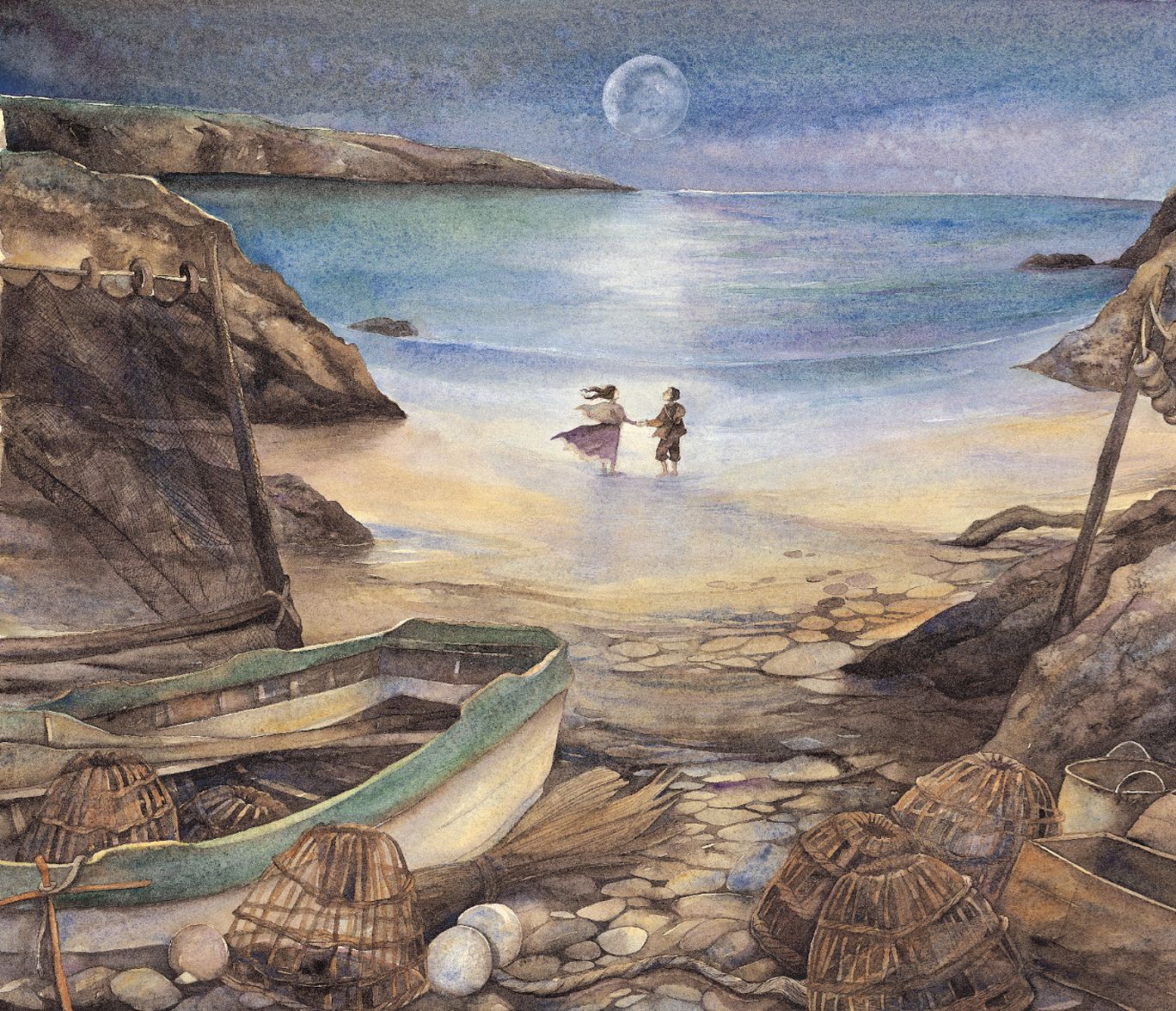

Ewan, who lives alone in Maes Y Mynydd meets a selkie woman. She loves music. She loves him. She gives him her skin. This is a story brought up to date. It is a story of respect, love and loss. Sparsely written, it tells of their courtship, their life together and her return to the sea. Between the lines is where much of the love lies. Do not think that Ewan does not miss his selkie wife when she returns to the sea, because it does not say so in the text. He loves her enough to return her skin when she needs it, knowing that she will leave him.

Stories live outside the pages they are written on. I know that Ewan goes to the sea every evening and plays his violin, far away on the other side of the world in the hope that the music will carry through the water to his wife and their son, far away. Maybe others will realise this to. The gift of this knowledge is in the final painting for those who read pictures as well as words.

This was the first book I wrote. Perhaps the first thing I ever wrote on a computer. Some how in this age of throw away I still have the edited text.

Writing the book wasn’t easy, but the key to catching the story in words came when a friend suggested I caught it first in pictures, then tried to catch the words that went with them. The story itself lived in my mind, but drawing it out, crafting it onto paper, that was what took time. And in that time it became more difficult as my own family fractured and split. Now, not only was I living in the physical landscape in which my book was set but I was also enduring the emotional landscape of the story. But there was a joy to be found in working all day in my studio, crafting the images for the book, then walking through the landscape in the evening, sometimes with cat and dog, sometimes with cats, dog and children.

I remember one evening sitting on the cliffs watching the seal pups with my children and a couple of their friends. Tom asked me, “are selkie’s real? I know mermaids are, but are selkies real too.” I told him to look into the eyes of a seal and tell me the answer to his own question.

It’s thought that the myth of the selkie rose from a time when the seas were cold and the gap between the northern lands was smaller. Small dark hunters crossed the open expanse of sea in kayaks made from articulated whale bone and seal skins. Coming ashore they would climb out from their boats, fold them, and stash them in safe places. Sometimes they would form relationships with local people but always they would return to their homelands, recovering their crafts, heading out to sea again. There’s a craft like this in the Ashmolean museum in Oxford.

But as Tom had said, he knew mermaids were real. So look into the eyes of a seal.

Over time I have gathered many selkie stories, drawn to the seal spirit as a moth is drawn to candlelight. Perhaps my favorite of all of these is The Brides of Rollrock Island by Margo Lanagan. Her book smells of the salt sea and moves with the sway of the water. Her character Miskaella has the power to draw the selkie out from the seal. She sits on the beaches knitting with seaweed and when we find out why it is such a blow for this book is full with dark secrets and beauty. I found the film and then the book of The Secret of Roan Innish, where the child is stolen away in a cradle from the island people to live among the seals, and Onedine about a man who falls in love with a selkie woman, maybe. The Great Silkie of Sule Skerry tells the heartbreaking song of a woman who gives birth to a seal child, paid by the selkie father. Such a tragic song told in few words. And here, Emily Portman sings songs of selkies:

Lullabies for selkie children:

Every year the Atlantic grey seals gather along the coast of Wales and bring their Seal Children into the world. Every year I am drawn to the beaches to watch. And now my book The Seal Children is available again in a beautiful hardback edition from Otter-Barry Books. For those who work in schools there are teachers notes on The Hamilton Trust website.

The Seal Children is set in a time when we were migrants. The people of Maes Y Mynydd became Quakers. The settlement was well known as a Quaker community. And the people wished to leave, to go to America, to make new lives for themselves and their families. They thought they were entering into an empty land. They hoped to escape the poverty, the hunger, the prejudice they lived with. They became a migrant people, refugees from poverty and persecution. This, then, is a tale from when we were migrants. People from Wales travelled to America, to Canada, to Australia, looking for better lives. Now there is again a massive movement of people around the planet. It is time to remember our history as we look to make a better future for all of us.

Here is a recording on soundcloud of me reading the book.

Win one of two copies of The Seal Children by Jackie Morris

Jackie Morris and her wonderful team over at Otter-Barry Books have offered two copies of The Seal Children for two lucky #FolkloreThursday readers, along with a selection of Jackie’s postcards!

Sign up for the #FolkloreThursday newsletter for details of how to be in with a chance to win by submitting your own selkie (or transformation) story, picture or other creative response (valid February 2017). The winning submission will be featured underneath Jackie’s article here on the blog once the competition closes.

And do tune in to #FolkloreThursday on Twitter this Thursday (2/2/17) to see Jackie’s live-tweet walk around Maes Y Mynydd, the setting of The Seal Children.

Here are the winning submissions!

Jackie Morris: Selkies – Curated tweets by FolkloreThurs